Abstract

Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHC) deficiency is mostly due to mutations in the X-linked E1α subunit gene (PDHA1). Some of the patients with PDHC deficiency showed clinical improvements with thiamine treatment. We report the results of biochemical and molecular analysis in a female patient with lactic acidemia. The PDHC activity was assayed at different concentrations of thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP). The PDHC activity showed null activity at low TPP concentration (1×10-3 mM), but significantly increased at a high TPP concentration (1 mM). Sequencing analysis of PDHA1 gene of the patient revealed a substitution of cysteine for tyrosine at position 161 (Y161C). Thiamine treatment resulted in reduction of the patient's serum lactate concentration and dramatic clinical improvement. Biochemical, molecular, and clinical data suggest that this patient has a thiamine-responsive PDHC deficiency due to a novel mutation, Y161C. Therefore, to detect the thiamine responsiveness it is necessary to measure activities of PDHC not only at high but also at low concentration of TPP.

The human pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHC), which is localized in the mitochondrial matrix, catalyzes the thiamine-dependent decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. It plays an important role in energy metabolism of the cell since it is an essential and rate-limiting enzyme connecting glycolysis with the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation. This enzyme complex consists of three catalytic components, pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1; EC 1.2.4.1), dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase (E2; EC 2.3.1.12), and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (E3; EC 1.8.1.4); two regulatory proteins, E1-kinase (EC 2.7.1.99) and phospho-E1-phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.43) ; and an additional protein known as the E3 binding protein (E3BP) (1). The first enzyme of the complex, thiamine pyrophosphate dependent pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1) which is a heterotetramer composed of two α and two β subunits, contains a thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) binding site (2). The great majority of PDHC deficiencies result from mutations in the X-linked E1α subunit gene (PDHA1), which is subjected to random inactivation. Highly variable X-inactivation contributes significantly to the wide spectrum of clinical features in most heterozygous females (3). Thiamine treatment is occasionally effective for some patients with PDHC deficiency. Among these patients, five mutations have been reported in a region outside the TPP binding site of the PDHA1 gene. In this study, we describe the results of biochemical and molecular analysis in a female PDHC deficiency patient with thiamine-responsiveness and a new missense mutation in the PDHA1 gene.

This female patient was born after 38 weeks of uncomplicated pregnancy to healthy nonconsanguineous parents. There was no perinatal hypoxic ischemic insult. Family history of neurodegenerative disorders was denied. Her neurodevelopments; motor, language and cognitive development, were delayed from the beginning. At 18 months of age, she was diagnosed to have spastic cerebral palsy. She finally walked at the age of 20 months. From this time, she occasionally had episodic lethargy, decreased mental state, and temporary deterioration of motor and cognitive function whenever she had a viral illness. At 4 yr of age, she admitted due to recurrent epileptic seizures. On admission, neurologic examination revealed drowsy mental state, tremor and increase muscle tone of both lower extremity. Laboratory tests revealed elevated arterial blood lactic acid (4.14 mM/L, normal range 0.7-2.1 mM/L), pyruvic acid (0.18 mM/L, normal range 0.01-0.10 mM/L) and elevated alanine (798 nM/mL, normal range 152-547 mM/L) concentration. Lactic acid level was also elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid (7.33 mM/L, normal range 0.7-2.1 mM/L). T2-weighted brain MRI revealed high signal intensity lesions in both basal ganglia suggestive of Leigh disease. Epileptic seizures were controlled with anticonvulsant treatments, and she finally recovered with some neurologic sequeles such as persistent irritability and cognitive dysfunction.

She was referred to Ajou University Medical Center for the evaluation of the lactic acidemia at the age of 5 yr. Neurologic examination on admission revealed irritability, cognitive dysfunction, hyperreflexia, increased muscle tone in lower extremity, and bilateral pathologic reflex. Laboratory tests revealed elevated arterial blood lactic acid (3.9 mM/L) and pyruvic acid (0.17 mM/L) concentration. L/P ratio (23) was elevated. Skin biopsy was done for the evaluation of PDHC and mitochondrial respiratory chain enzyme assay. PDHC activity in cultured skin fibroblasts was mildly reduced to 0.804 nM/min/mg protein (normal: 1.13-6.67 nM/min/mg protein). All the mitochondrial respiratory chain enzyme activities were normal. Thiamine treatment at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day was started. On 5 months of thiamine treatment, neurologic manifestations which were observed on admission; irritability, cognitive dysfunction, hyperreflexia, and bilateral pathologic reflex, were gradually improved with some residual clumsiness. Recently estimated arterial blood lactic acid (2.1 mM/L) and pyruvic acid (0.082 mM/L) concentrations were decreased to near normal range. Now she can attend regular nursery school without difficulties.

The PDHC activity was measured in cultured skin fibroblasts by measuring 14CO2 production from [1-14C]-labeled pyruvate, modified from the method of Sheu et al. (4). Patient's fibroblasts was obtained from skin biopsy and cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 1×10-2 mM thiamine-HCl. To compare the TPP responsiveness, we also tested the activity of the TPP unresponsive-PDHC deficient fibroblasts with an AAGT duplication at nucleotide 1162. The activity of the PDHC was assayed at different concentrations of TPP (1×10-3, 1×10-2, 0.1 and 1.0 mM) after the activation of PDHC using sodium dichloroacetate (DCA).

Mutation analysis of PDHA1 was performed on genomic DNA samples, which was extracted from whole blood cells of the patient and also her mother. Amplification of individual exons of the PDHA1 gene from genomic DNA was performed using primer pairs and conditions as described in (3). Exonic PCR products were sequenced directly using appropriate amplification primers by an ABI 200 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). To confirm that Y161C is a disease-causing mutation, the sequences of exon 5 were analyzed from seventy independent DNA samples in healthy children (35 males and 35 females). Y161C created a site for the restriction enzyme Fau I, resulting in two novel bands, therefore genomic PCR products of exon 5 were digested with Fau I.

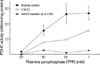

DCA-activated PDHC activity in cultured fibroblasts of the patient was assayed at different concentrations of TPP (1×10-3, 1×10-2, 0.1 and 1.0 mM). Cultured fibroblasts in normal control and patient showed an exponential increase in PDHC activity with a gradual increase of TPP concentration. Normal cells showed 6.6% of maximal PDHC activity in low TPP concentration (1×10-3 mM), and the addition of 0.1 mM TPP restored full activity, with no further change in PDHC activity between 0.1 and 1.0 mM TPP. However, PDHC activity in the patient showed null activity in low concentration of TPP (1×10-3 mM), but her PDHC activities significantly increased up to 58% of the PDHC activity of normal cells at a high concentration of TPP (1.0 mM), as shown in Fig. 1. There was no increase of PDHC activity in thiamine-unresponsive patient's cell line which has an AAGT duplication at nucleotide 1162.

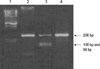

Direct sequencing of entire coding region of the PDHA1 gene of the patient revealed both a A (normal) and G (mutant) at nucleotide 482 in exon 5, resulting in the presence of a tyrosine (codon TAC) at amino acid position 161 of the wild type E1α protein and a cysteine (codon TGC) in a mutant protein (Fig. 2). No other mutation except for Y161C was found in the PDHA1 gene of this patient and Y161C was not detected in the genomic DNA of the patient's mother (Fig. 3). To confirm that Y161C is disease-causing mutation, we screened the existence of this mutation from seventy unrelated healthy controls. The PCR products of exon 5 were digested with the restriction enzymes, Fau I, as a result this mutation was not found in seventy unrelated healthy Korean.

The great majority of thiamine-responsive PDHC deficiency results from mutations in the X-linked PDHA1 gene which cause a decreased affinity of PDHC for TPP and a consequent defective enzymatic activation. Clinical manifestations of PDHC deficiency in female are remarkably variable because mutations are present in one of the two X-chromosomes in affected females. Random patterns of X-inactivation will lead to variable expression of the mutant and normal genes in different tissues. Therefore, sufficient ATP is produced in normal cells but severe ATP deficiency occurs in affected cells. The proportion of mutant genes to normal genes in different tissues determine variable phenotypic expression. Severe organ dysfunctions occur especially in the brain, muscle, and heart which usually depend on aerobic oxidation of glucose for most of its energy supply. There are no effective treatment modalities. However, there are a few case reports of thiamine-responsive PDHC deficiency in the literatures reported by Naito et al. (5, 6). According to Naito et al., high concentrations of TPP in vitro as well as treatment with thiamine in vivo is effective in thiamine-responsive PDHC deficiency. Therefore, it is necessary to measure PDHC activity at low TPP concentration in order to prevent diagnostic errors. Furthermore, PDHC assays with serial TPP concentrations could detect patients with thiamine-responsive PDHC deficiency (7).

We described here the identification of a novel mutation, Y161C, in female patient with PDHC deficiency who showed neuroradiological findings suggestive of Leigh disease, delayed motor development and intermittent neurologic deterioration with intercurrent infection. In order to compare TPP responsiveness, we used the 1162ins-mutant for positive control in PDHC activity analysis. The 1162ins-mutant is missing three C-terminal amino acids, Ser-Val-Ser, and these three amino acids are known to play a critical role in the structural integrity of the E1 component rather than in its catalytic activity. It is suggested that mutant E1α protein of 1162ins-mutant causes mis-folding of both subunits leading to their mutual destruction (8). However, in our patient thiamine responsiveness was found at serial TPP concentrations on contrary to the 1162ins-mutant showing unresponsiveness (Fig. 1). Therefore, the PDHC deficiency in this patient was not due to mutual destruction of E1 component but due to a decreased affinity of PDHC for TPP. Furthermore, clinical improvements after thiamine administration correlated to in vitro enzymatic studies in this patient. These results not only indicate the presence of thiamine responsive PDHC deficiency in this patient, but also support that the thiamine-responsive PDHC deficiency should be diagnosed on the basis of the measurement of PDHC activity under serial TPP concentrations.

However, there was a difference in the level of PDHC activities at low TPP concentrations compared to other reports. According to Naito et al., normal cells showed approximately 50% of the full PDHC activity in the absence of TPP and addition of 1×10-5 mM TPP restored the full enzyme activity (6). In another report, normal cells displayed PDHC activity of 7% of the maximal level without TPP, and the addition of 1×10-3 mM TPP restored full PDHC activity (9). However, PDHC activity of normal cells showed 6% of the full PDHC activity at 1×10-3 mM TPP in this study (Fig. 1). This difference could be derived from two possible explanations. One possible explanation is that it may be due to an absence of dephosphorylation step in our method (4). The role of PDHC phosphatase is dephosphorylation of PDHC with concomitant activation of this enzyme. Therefore, analysis of PDHC activity without dephosphorylation step might lower the enzyme activity significantly. The other possible explanation is that very low enzyme activity at low TPP concentration might be due to relatively higher TPP concentration in the culture medium. Naito et al. suggested that the PDHC activity in the cultured cells with thiamine-responsive mutations might depend not only on the concentration of TPP in the reaction mixture, but also in the concentration of thiamine in the culture medium or within the cultured cells (5). TPP concentration in normal human blood is 1×10-4 mM but the concentration of thiamine-HCl in the culture medium used for our study was 1×10-2 mM (10). It is approximately 100 times higher than those in normal human blood (5, 6). Therefore, it might be possible that the normal cell lines would be adjusted to a higher TPP concentration in culture medium and they could not react sensitively at low TPP concentration in the reaction mixture. The PDHC activities of the 1162ins-mutant and patient showed null activities in TPP concentration (1×10-3 mM). These results might also have been due to a difference in the method or the higher TPP concentration in the culture medium, or the characteristics of these mutations.

In relation to the TPP-binding sites, there are two types of mutations: those directly interacting with the Ca++-pyrophosphate complex of TPP and those located outside the TPP-binding site but inhibit TPP binding (5). The E1α subunit has been carried the TPP binding motif GDG X26/27 NN common to all TPP-utilizing enzyme, and it is thought to locate in the region from amino acid 195 in exon 6 to amino acid 225 in exon 7 (9). In the patients with PDHC deficiency responding to TPP, five mutations in the region outside the TPP-binding site of the E1α subunit gene have been reported previously: H44R, R88S, G89S, R263G, and V3869fs (6, 12-14). On the contrary, in the case of a patient with Y243S mutation, which is located outside the conserved TPP-binding motif, the PDHC activity in cultured fibroblasts was very low even in the presence of high TPP concentration. Western blot analysis showed that the immunoreative signals corresponding to E1α and E1β subunit were weak (9). The Y243S mutation led to structural consequences affecting the interaction and stability of the α2β2 heterotetramer. Therefore, functional defects in the E1α enzyme could be quite different according to not only the location of mutations but also nature of amino acid subsititutions in the region outside the TPP-binding site.

For this reason, we suggest that the Y161C mutation, which is located in a region outside the conserved TPP-binding motif, probably induced a minimal alteration in the amino acid sequence affecting only E1α protein folding rather than the assembly of the α2β2 heterotetramer. However, expression studies must be needed to know the important information about the structural and functional role of the affected amino acids in PDHC catabolism and in regulation or interaction with the other components, especially the E1β subunit. They may lead to an understanding of exact mechanism of thiamine responsiveness in this patient with Y161C mutation.

PDHA1 gene is located on X-chromosome. In affected females, mutations could be present in one of the two X-chromosomes, and random patterns of X-inactivation will lead to variable expression of the mutant and normal genes in different tissues. Whether clinically manifested or not, it will depend on the degree of residual PDHC activity reflecting the proportion of cells expressing the normal E1α subunit. However, all the male havoring PDHA1 gene mutations always present clinical features of PDHC deficiency. We did not screened Y161C mutation in her father who did not showed any clinical evidences of pyruvate metabolic disorder. In this patient Y161C mutation may have occurred de novo.

In conclusion, we identified a new mutation, Y161C, causing thiamine-responsive PDHC deficiency. No other mutations were found in the PDHA1 gene and this mutation was not present in the genomic DNA from seventy unrelated controls. Clinical and biochemical parameters were improved by a high dose of thiamine treatment in this patient. Thiamine-responsive PDHC deficiency was confirmed by in vitro studies showing a thiamine-responsive functional defect in cultured skin fibroblasts of the patient.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Effect of TPP on the activity of DCA-activated PDHC in cultured fibroblasts from normal subject and two patients with PDHC deficiency (Y161C; a patient with thiamine-responsive PDHC deficiency, AAGT insertion at nt.1162; positive control which has non-responsive PDHC deficiency).

Fig. 2

Electropherograms of DNA sequencing for Y161C mutation. (A) Normal sequence of exon 5. (B) Patient sequence has both a A (normal) and G (mutant) at nucleotide 482, resulting in the presence of a tyrosine (codon TAC) and cysteine (codon TGC) at position 161.

Fig. 3

Detection of the 482 A-to-G substitution in the E1α gene. PCR-amplified products (206 bp) of exon 5 were digested by Fau I, which creates two fragments of 108 bp and 98 bp in the case of the mutated sequence (Lane 1, Marker; Lane 2, Normal subject; Lane 3, Patient (heterozygous); and Lane 4, Patient's mother).

References

1. Lissens W, De Meirleir L, Seneca S, Liebaers I, Brown GK, Brown RM, Ito M, Naito E, Kuroda Y, Kerr DS, Wexler ID, Patel MS, Robinson BH, Seyda A. Mutations in the X-linked pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1) α subunit gene (PDHA1) in patients with a pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency. Hum Mutat. 2000. 15:209–219.

2. Robinson BH. Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. Lactic acidemia (disorders of pyruvate carboxylase, pyruvate dehydrogenase). The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. 2001. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;2275–2295.

3. Matsuda J, Ito M, Naito E, Yokota I, Kuroda Y. DNA diagnosis of pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency in female patients with congenital lactic acidaemia. J Inher Metab Dis. 1995. 18:534–546.

4. Sheu KF, Hu CW, Utter MF. Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in normal and deficient fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1981. 67:1463–1471.

5. Naito E, Ito M, Yokota I, Saijo T, Matsuda J, Ogawa Y, Kitamura S, Takada E, Horii Y, Kuroda Y. Thiamine-responsive pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency in two patients caused by a point mutation (F205L and L216F) within the thiamine pyrophosphate binding region. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002. 1588:79–84.

6. Naito E, Ito M, Takeda E, Yokota I, Yoshijima S, Kuroda Y. Molecular analysis of abnormal pyruvate dehydrogenase in a patient with thiamine-responsive congenital lactic academia. Pediatr Res. 1994. 36:340–346.

7. Di Rocco M, Lamba LD, Minniti G, Caruso U, Naito E. Outcome of thiamine treatment in a child with Leigh disease due to thimanine-responsive pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2000. 4:115–117.

8. Saijo T, Naito E, Ito M, Yokota I, Matsuda J, Kuroda Y. Stable restoration of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in E1-defective human lymphoblastoid cells: Evidence that three C-terminal amino acids of E1α are essential for the structural integrity of heterotetrameric E1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996. 228:446–451.

9. Benelli C, Fouque F, Redonnet-Vernhet I, Malgat M, Fontan D, Marsac C, Dey R. A novel Y243S mutation in the pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 alpha gene subunit: Correlation with thiamine pyrophosphate interaction. J Inher Metab Dis. 2002. 25:325–327.

10. Kitamori N, Itokawa Y. Pharmacokinetics of thiamine after oral administration of thiamine tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide to humans. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 1993. 39:465–472.

11. Robinson BH, Chun K. The relationships between transketolase, yeast pyruvate decarboxylase and pyruvate dehydrogenase of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. FEBS Lett. 1993. 328:99–102.

12. Naito E, Ito M, Yokota I, Saijo T, Chen S, Maehara M, Kuroda Y. Concomitant administration of sodium dichloroacetate and thiamine in West syndrome caused by thiamine-responsive pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency. J Neurol Sci. 1999. 171:56–59.

13. Naito E, Ito M, Yokota I, Saijo T, Matsuda J, Osaka H, Kimura S, Kuroda Y. Biochemical and molecular analysis of an X-linked case of Leigh syndrome associated with thiamine-responsive pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1997. 20:539–548.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download