Abstract

Granulocytic sarcoma (GS) is an extramedullary tumor composed of immature myeloid cells, typically occurring during the course of acute myelogenous leukemia. Nonleukemic GS, that is, GS with no evidence of overt leukemia and no previous history of leukemia, is very rare, and even more unusual is nonleukemic GS of the bile duct. We report a case of nonleukemic GS of the bile duct. The patient was initially misdiagnosed as a bile duct carcinoma arising in the hilum of the liver (so-called Klatskin tumor), and received a right lobectomy of the liver. Histological examination of the tumor yielded the diagnosis of GS, and the bone marrow biopsy did not show any evidence of leukemia. Considering the risk of subsequent development of overt leukemia, the patient was treated with two cycles of combination chemotherapy as used in the cases of acute myelogenous leukemia. To date, he has remained free of disease 15 months after treatment.

Granulocytic sarcoma (GS) is a localized tumor composed of immature myeloid cells in extramedullary sites. It usually presents concomitantly with or after the onset of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), blastic phase of chronic myelogenous leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome (1-3). On rare occasions, GS may present as nonleukemic GS. By definition, nonleukemic GS occurs without present overt leukemia, and in the absence of any past history of AML, myelodysplasia, or myeloproliferative disorders (2-4). Nonleukemic GS may involve any part of the body, and the most common sites of involvement are skin, subcutaneous tissue, lymph nodes, central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, mediastinum, bone, breast, ovary and uterus (2,3,5). Although nonleukemic GS may be found in any location, primary occurrence in the bile duct is extremely rare. In this report, we describe an extremely rare case of a nonleukemic GS of the bile duct, which was initially misdiagnosed as a bile duct carcinoma arising in the hilum of the liver (so-called Klatskin tumor).

A 44-yr-old man was hospitalized because of jaundice. Physical examination revealed normal findings except jaundice. His past medical history was unremarkable. The complete blood count showed hemoglobin of 15 g/dL, white blood cell count of 8,200/µL (differential 79% segmented neutrophils, 15% lymphocytes, 5% monocytes, and 1% eosinophils), and platelet count of 248,000/µL. Liver function test showed elevation of total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase (15.3 mg/dL, 9.4 mg/dL and 298 IU/L, respectively). Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed thickening of common bile duct wall, luminal narrowing at common hepatic duct level and mild, diffuse dilatation of intrahepatic duct (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance cholangiography showed dilatation of both intrahepatic duct and right posterior duct (Fig. 2). Based on these findings, a common hepatic duct cancer (Klatskin tumor) was thought to be the cause of the obstructive jaundice. He underwent a right lobectomy of the liver.

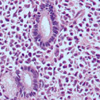

Histological examination of the tumor showed diffuse thickening of the common bile duct wall with encroachment of the lumen and obliteration of the mucosal folds by the dense cellular infiltrate. The great majority of the cells in the infiltrate consisted of myeloid precursors with large round to oval cells with slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm and round to oval vesicular nuclei, admixed with a minor population of more mature myeloid forms including eosinophils (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemical stains showed tumor cells positive for leukocyte common antigen (CD 45) and myeloperoxidase (Fig. 4), and negative for CD 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 21, 23, 56 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy showed neither significant abnormalities nor evidence of myelodysplasia or leukemic infiltration. In consequence of these findings, the tumor was diagnosed as nonleukemic GS.

Considering the risk of subsequent development of overt leukemia (3), the patient received antileukemic induction chemotherapy consisting of cytarabine 200 mg/m2/day (days 1-5) and daunorubicin 45 mg/m2/day (days 1-3), and a course of consolidation with high dose cytarabine (cytarabine 6 g/m2/day, days 1, 3, 5) subsequently. To date, he has remained free of disease for 15 months.

Nonleukemic GS is very rare disease. Although nonleukemic GS may involve any part of the body, nonleukemic GS of the bile duct is extremely rare.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been only 1 case report of nonleukemic GS of the bile duct in the medical literatures. Matsueda et al. (6) reported a patient who present with obstructive jaundice and underwent endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage. He developed acute AML within 1 month.

A frequent problem reported with nonleukemic GS is initial misdiagnosis. Correct initial diagnosis of nonleukemic GS is very important because misdiagnosis could lead to inappropriate treatment and hence, to the risk of missing a chance for cure. However, due to its rarity, nonleukemic GS is frequently misdiagnosed as other common malignancies, as was the case with our patient being initially misdiagnosed as a bile duct carcinoma. Even after the histologic examination, GS may be misdiagnosed as other malignancies, most often as lymphoma (2,3). Because considerable cases of GS do not show morphologic evidence of granulocytic differentiation, could exhibit features mimicking lymphoma and may co-express myeloid and lymphoid markers, histologic diagnosis of GS can be difficult if it is not suspected (1,7). In one case series, 75% of the cases with nonleukemic GS were initially misdiagnosed, 50% as lymphoma, and 25% as nonhematopoietic neoplasm (2). In another case series, 35 (47%) of 74 patients with nonleukemic GS were initially misdiagnosed (5). Among them, 31 patients were mistaken for lymphoproliferative disorders. The correct diagnoses were usually made when the lesion recurred or after overt leukemia developed thereafter (2,5). Consequently, treatment was inappropriate or delayed under the initial misdiagnosis in these cases. Thus, for correct initial diagnosis and adequate therapy, it is important to suspect the possibility of nonleukemic GS and to apply appropriate immunohistochemical staining for differential diagnosis.

Nonleukemic GS represents therapeutic dilemma as well as a diagnostic one because the optimal therapy for nonleukemic GS has not been determined. Several previous reports showed that more than 80% of patients with nonleukemic GS who were treated by surgical excision or local radiation therapy eventually developed overt systemic leukemia within a matter of months (1,3,8,9), which suggests that local treatments such as surgical excision or radiation therapy would not be sufficient for the treatment of nonleukemic GS. For this, the importance of systemic chemotherapy as used for AML early in the course of the disease was advocated by several retrospective studies (2,5,10). Eshghabadi et al. (2) found that in the 19 patients who received surgical or radiation therapy for nonleukemic GS eventually developed AML. In contrast, only 5 (42%) of 11 patients treated with systemic chemotherapy developed rospective review of 90 nonleukemic GS cases, patients treated with systemic chemotherapy had a decreased probability of developing AML and experienced longer overall survival. In all, 59 (66%) of the 90 patients developed AML at a median 9 months after the diagnosis of nonleukemic GS and the median overall survival was 22 months. A total of 49 (54%) of 90 patients received chemotherapy and were less likely to develop AML as compared with those who did not receive chemotherapy (41% vs. 71%, p=0.001). In addition, leukemia occurred significantly later in those patients who received systemic chemotherapy. The median time from diagnosis of nonleukemic GS to leukemia was 36 months in patients treated with chemotherapy compared with 6 months in untreated patients. Most importantly, the overall survival was longer in the patients who received chemotherapy than in the patients who did not (more than 50% alive after a median follow up of 25 months compared with a median survival of 13 months in those who did not receive chemotherapy). Of note is that multivariate analysis revealed that neither radiation nor surgery alone had any effect on survival. Yamauchi and Yasuda (5) reported 74 cases of nonleukemic GS. These patients were divided into 3 groups by therapeutic regimens; Group I included 12 patients who received only biopsy or surgical resection of the tumor, Group II was 20 patients who received local radiation, and Group III consisted of 42 patients who received systemic chemotherapy. The nonleukemic period after the diagnosis of GS was significantly longer in Group III than in the other groups (median, 12 months in Group III vs. 3 and 6 months in Group I and II, respectively). According to the findings of the above studies, it appeared that patients with nonleukemic GS should receive AML type systemic chemotherapy at the time of diagnosis, and surgery and/or radiation therapy alone would be insufficient treatment of nonleukemic GS. In the present case, considering the risk of subsequent development of overt leukemia, we treated the patient with two cycles of AML type combination chemotherapy and he has remained free of disease 15 months after treatment. A few patients with nonleukemic GS also underwent allogeneic or autologous bone marrow transplantation (10). However, the efficacy of allogeneic or autologous bone marrow transplantation in the therapy of nonleukemic GS has not been defined.

In conclusion, nonleukemic GS is frequently misdiagnosed as other more common malignancies because of its rarity and clinico-pathological features mimicking other malignancies. With a high index of suspicion, the application of immunohistochemical techniques enables the differential diagnosis from aggressive lymphoma that represents the commonest misdiagnosis. Considering the poor outcome after local treatment for nonleukemic GS, the patients with nonleukemic GS should be treated with intensive AML type systemic chemotherapy early in the course of the disease.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Abdominal computed tomography demonstrating thickening of common bile duct wall, luminal narrowing at common hepatic duct level (A), and mild, diffuse dilatation of intrahepatic duct (B).

Fig. 2

Magnetic resonance cholangiography showing dilatation of both intrahepatic duct and right posterior duct.

Fig. 3

The great majority of the cells in the infiltrate consists of myeloid precursors with large round to oval cells with slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm and round to oval vesicular nuclei, admixed with a minor population of more mature myeloid forms including eosinophils (hematoxilin-eosin, ×400).

References

1. Neiman RS, Barcos M, Berard C, Bonner H, Mann R, Rydell RE, Bennett JM. Granulocytic sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 61 biopsied cases. Cancer. 1981. 48:1426–1437.

2. Eshghabadi M, Shojania AM, Carr I. Isolated granulcytic sarcoma: Report of a case and review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 1986. 4:912–917.

3. Meis JM, Butler JJ, Osborne BM, Manning JT. Granulocytic sarcoma in nonleukemic patients. Cancer. 1986. 58:2697–2709.

4. Menasce LP, Banerjee SS, Beckett E, Harris M. Extra-medullary myeloid tumour (granulocytic sarcoma) is often misdiagnosed: a study of 26 cases. Histopathology. 1999. 34:391–398.

5. Yamauchi K, Yasuda M. Comparison in treatments of nonleukemic granulocytic sarcoma: report of two cases and a review of 72 cases in the literature. Cancer. 2002. 94:1739–1746.

6. Matsueda K, Yamamoto H, Doi I. An autopsy case of granulocytic sarcoma of the porta hepatis causing obstructive jaundice. J Gastroenterol. 1998. 33:428–433.

7. Bayle C, Romdhane NB, Bastard C, Vannier JP, Hayat M, Lemerle J, Bernard A. Acute leukemia with extramedullary presentation and mixed myeloid and lymphoid expression. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1986. 3:293–296.

8. Spahr J, Behm FG, Schneider V. Preleukemic granulocytic sarcoma of cervix and vagina: initial manifestation by cytology. Acta Cytol. 1982. 26:55–60.

9. Krause JR. Granulocytic sarcoma preceding acute leukemia: a report of six cases. Cancer. 1979. 44:1017–1021.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download