Abstract

Langerhans cell sarcoma (LCS) is a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that have overtly malignant cytologic features. It is a very rare disease and theoretically, it can present de novo or progress from an antecedent Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). However, to our knowledge, LCS arising from an antecedent LCH has not been reported on. We present here a case of LCS arising from a pulmonary LCH. A 34 yr-old man who was a smoker, had a fever and a chronic cough. Computed tomographic (CT) scan revealed multiple tiny nodules in both lungs. The thoracoscopic lung biopsy revealed LCH. The patient quit smoking, but he received no other specific treatment. One year later, the follow up chest CT scan showed a 4 cm-sized mass in the left lower lobe of the lung. A lobectomy was then performed. Microscopic examination of the mass revealed an infiltrative proliferation of large cells that had malignant cytologic features. Immunohistochemical stains showed a strong reactivity for S-100 and CD68, and a focal reactivity for CD1a. We think this is the first case of LCS arising from LCH.

Langerhans cell sarcoma (LCS) is a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that have overtly malignant cytologic features (1,2). It is a very rare disease (2-11) and theoretically, it can present de novo or it can progress from an antecedent Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) (1). However, to our knowledge, LCS arising from an antecedent LCH has not been reported on. We present here a case of LCS arising from pulmonary LCH.

The patient was a 34-yr-old man who presented with complaints of fever and a chronic cough. He was a smoker and had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis that had been treated and cured. A computed tomographic (CT) scan revealed multiple tiny nodules in both lungs. A thoracoscopic lung biopsy was taken from the right upper lobe. The microscopic examination revealed a typical LCH. The tumor cells had vesicular and grooved nuclei, and they formed small aggregations around the bronchioles (Fig. 1). The tumor cells were strongly positive for S-100 protein, vimentin, CD68 and CD1a. There were infiltrations of lymphocytes and eosinophils around the tumor cells. With performing additional radiologic examinations, no other organs were thought to be involved. He quit smoking, but he received no other specific treatment. He was well for the following one year. After this, a follow-up CT scan was performed and it showed a 4 cm-sized mass in the left lower lobe, in addition to the multiple tiny nodules in both lungs (Fig. 2). A needle biopsy specimen revealed the possibility of a sarcoma; therefore, a lobectomy was performed.

Grossly, a 4 cm-sized poorly-circumscribed lobulated gray-white mass was found (Fig. 3), and there were a few small satellite nodules around the main mass. Microscopically, the tumor cells were aggregated in large sheets and they showed an infiltrative growth. The cytologic features of some of the tumor cells were similar to those seen in a typical LCH. However, many tumor cells showed overtly malignant cytologic features such as pleomorphic/hyperchromatic nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Fig. 4), and multinucleated tumor giant cells were also found. There were numerous mitotic figures ranging from 30 to 60 per 10 high power fields, and some of them were abnormal. A few foci of typical LCH remained around the main tumor mass.

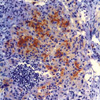

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were strongly positive for S-100 protein (Fig. 5) and vimentin; they were also positive for CD68 (Dako N1577, Clone KPI), and focally positive for CD1a (Fig. 6), and they were negative for cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen, CD3, CD20 and HMB45. The ultrastructural analysis failed to demonstrate any Birbeck granules in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells.

Now, at five months after lobectomy, the patient is doing well with no significant change in the radiologic findings.

The clinical spectrum of LCH varies from the indolent lesion to the more aggressive and often fatal disease. Researches attempting to relate the histological findings to the prognosis have generally been unrewarding (12,13). Mild atypia and a high proliferative rate were not always associated with unfavorable prognosis (12) and these features did not indicate malignancy. Instead, the prognosis was best predicted by the clinical parameters. In one report (14), disease free survival was achieved in all the patients having isolated bone lesions. By contrast, 20% of the patients with multisystem involvement had a progressive disease course despite extensive treatment. However, the marked atypia was generally associated with an aggressive clinical course and distant metastasis (2-6,9-11). Therefore, the cases of LCH with markedly atypical tumor cells should be called LCS, and these cases should be considered as a separate entity apart from LCH (1,2,9).

Langerhans cell sarcoma is an exceedingly rare cancer, and we found only 18 cases in the English-language literature. These were 9 cases (7 cases had aggressive clinical course and 2 cases had a benign clinical course.) reported on by Ben-Ezra et al. (2), and 9 isolated cases (3-11). Of the 19 cases, including our case, the skin was involved at the time of diagnosis in 9 cases, and the skin was the only organ involved in 3 of the cases. The lymph nodes, spleen, liver, bone marrow, thymus, lung and kidney were the other organs frequently involved. The heart was involved in two cases (2,3). The age at the time of diagnosis ranged from newborn (2) to 76 yr (7) with the average age being 37. Eleven patients were male and 8 were female. Of the 19 patients, 11 died within 2 yr, and one died at 40 months. Of the remaining 8 patients who survived their disease, the skin was the only organ involved in 3 patients, and 4 of the patients had been followed-up for less than 1 yr.

Tani et al. (9) suggested the following criteria for the diagnosis of malignant neoplasm of Langerhans cells: 1) proliferation of the typical Birbeck granule-containing tumor cells, and 2) such malignant cytological features as atypia and frequent mitotic figures. Although we could not demonstrate Birbeck granules, we were not dissuaded from making the diagnosis of LCS. Cells may lose their ultrastructural characteristics or their immunophenotype as they become less differentiated and more atypical. In fact, Ben-Ezra et al. (2) could demonstrate Birbeck granules in only 3 of the nine cases they reported on. Histiocytic sarcoma and other dendritic cell tumors should be included in the differential diagnoses. These tumors were excluded because our case was focally, yet definitely positive for CD1a (15,16).

It has been said that LCS can present de novo or progress from an antecedent LCH (1). However, to our knowledge, LCS arising from an antecedent LCH has not been reported on. Two of the patients reported on by Ben-Ezra et al. (2) had benign Langerhans cells in one organ, and they had atypical ones in other organs. However, the tumors arose from different organs and the relation between the tumors was not stated.

We think our case is the first case of LCS arising from LCH in that 1) it was preceded by a typical LCH in the same organ, 2) the tumor cells were markedly atypical, but they had some features of LCH remaining, and 3) the tumor cells were positive for S-100 protein, CD68 and CD1a.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Many tumor cells show grooved nuclei. There is an infiltration of lymphocytes and eosinophils around the tumor cells (H-E stain, ×200).

Fig. 2

A CT scan shows multiple tiny nodules in both lungs and a lobulated mass in the left lower lobe.

References

1. Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW. WHO classification of tumours: Pathology and genetics of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 2001. Lyon: IARCPress;283.

2. Ben-Ezra J, Bailey A, Azumi N, Delsol G, Stroup R, Sheibani K, Rappaport H. Malignant histiocytosis X. A distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1991. 68:1050–1060.

3. Imamura M, Sakamoto S, Hanazono H. Malignant histiocytosis: a case of generalized histiocytosis with infiltration of Langerhans' granule-containing histiocytes. Cancer. 1971. 28:467–475.

5. Wood C, Wood GS, Deneau DG, Oseroff A, Beckstead JH, Malin J. Malignant histiocytosis X. Report of a rapidly fatal case in an elderly man. Cancer. 1984. 54:347–352.

6. Bonetti F, Knowles DM, Chilosi M, Pisa R, Fiaccavento S, Rizzuto N, Zamboni G, Menestrina F, Fiore-Donati L. A distinctive cutaneous malignant neoplasm expressing the Langerhans cell phenotype: synchronous occurrence with B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 1985. 55:2417–2425.

7. Goldberg NS, Bauer K, Rosen ST, Caro WA, Marder RJ, Zugerman C, Rao S, Variakojis D. Histiocytosis X. Flow cytometric DNA-content and immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1986. 122:446–450.

8. Delabie J, De Wolf-Peeters C, De Vos R, Vandenberghe E, Kennes K, De Jonge I, Desmet V. True histiocytic neoplasm of Langerhans' cell type. J Pathol. 1991. 163:217–223.

9. Tani M, Ishii N, Kumagai M, Ban M, Sasase A, Mishima Y. Malignant Langerhans cell tumor. Br J Dermatol. 1992. 126:398–403.

10. Itoh H, Miyaguni H, Kataoka H, Akiyama Y, Tateyama S, Marutsuka K, Asada Y, Ogata K, Koono M. Primary cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis showing malignant phenotype in an elderly woman: report of a fatal case. J Cutan Pathol. 2001. 28:371–378.

11. Misery L, Godard W, Hamzeh H, Levigne V, Vincent C, Perrot JL, Gentil-Perret A, Schmitt D, Cambazard F. Malignant Langerhans cell tumor: a case with a favorable outcome associated with the absence of blood dendritic cell proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003. 49:527–529.

12. Risdall RJ, Dehner LP, Duray P, Kobrinsky N, Robison L, Nesbit ME Jr. Histiocytosis X (Langerhans' cell histiocytosis). Prognostic role of histopathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1983. 107:59–63.

13. Frederiksen P, Thommesen P. Histiocytosis X: II. Histologic appearance correlated to prognosis and extent of disease. Acta Radiol Oncol Radiat Phys Biol. 1978. 17:10–16.

14. Howarth DM, Gilchrist GS, Mullan BP, Wiseman GA, Edmonson JH, Schomberg PJ. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: diagnosis, natura history, management, and outcome. Cancer. 1999. 85:2278–2290.

15. Shinzato M, Shamoto M, Hosokawa S, Kaneko C, Osada A, Shimizu M, Yoshida A. Differentiation of Langerhans cells from interdigitating cells using CD1a and S-100 protein antibodies. Biotech Histochem. 1995. 70:114–118.

16. Lee JR, Choi GS, Koo SW, Lee SC, Kim YK. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as a solitary nodule. Korean J Dermatol. 2001. 39:459–462.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download