Abstract

Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (CPAN) is an uncommon form of vasculitis involving small and medium sized arteries of unknown etiology. The disease can be differentiated from polyarteritis nodosa by its limitation to the skin and lack of progression to visceral involvement. The characteristic manifestations are subcutaneous nodule, livedo reticularis, and ulceration, mostly localized on the lower extremity. Arthralgia, myalgia, peripheral neuropathy, and constitutional symptoms such as fever and malaise may also be present. We describe a 34-yr-old woman presented with severe ischemic change of the fingertip and subcutaneous nodules without systemic manifestations as an unusual initial manifestation of CPAN. Therapy with corticosteroid and alprostadil induce a moderate improvement of skin lesions. However, necrosis of the finger got worse and the finger was amputated.

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is an aggressive, often fatal form of necrotizing vasculitis associated with multiorgan involvement. However, cutaneous polyartetitis nodosa (CPAN) is a more benign form of disorder, which affects the small and medium sized arteries, confined to the skin (1). For a long time, it has been a matter of debate whether CPAN is a distinct clinical entity or a mere early phase of PAN. Recently, several studies with long term follow up have shown that CPAN rarely progress into PAN (2, 3). Therefore CPAN is considered to be a distinct entity characterized by the rarity of systemic involvement, chronic disease course, and good prognosis (2, 4, 5). Subcutaneous tender nodule, livedo reticularis, and ulceration are the hallmarks of the disease. Arthralgia, myalgia, neuropathy, and constitutional symptoms such as fever and malaise may also be present (2, 4). Although the etiology is still unknown, an immune mediated mechanism has been postulated. Various factors have been implicated including drugs, tuberculosis, hepatitis, and streptococcal infections (2, 6, 7). This disorder represents a chronic and benign course that exhibits a tendency towards relapses and remissions (2, 8).

We present the case of a patient with severe ischemic loss of fingertip as an unusual initial manifestation of CPAN.

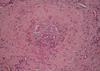

A 34-yr-old woman was admitted to the hospital because of multiple painful nodules in both legs and bluish hue in the left 4th fingertip, which was first recognized few days before admission. She did not smoke, and there was no history of Raynaud's phenomenon, frostbite, or recurrent fetal loss. About one month prior to admission, she had a sore throat. Physical examination revealed blood pressure of 100/70 mm Hg, pulse of 68/min, respiratory rate of 22/min, and the temperature was 36.5℃. Multiple erythematous tender nodules on both legs and palms with shallow ulcers over the lateral malleolus were found. Necrotic change of the left 4th finger tip up to distal interphalangeal joint area was found (Fig. 1). Radial pulses were symmetric and strong. Allen's test was normal. Cardiac and abdominal examinations were normal. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasonography were normal findings. Transthoracic echocardiography showed neither valvular abnormality nor vegetation. Laboratory test showed hemoglobin 11.2 g/dL, WBC 17,910/µL, platelet 396,000/µL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 60 mm/hr, antistreptolysin O (ASO) 378 IU/mL (normal range, 0-200), and C-reactive protein 14.1 mg/dL (normal range <0.5). Renal and liver function tests were normal. Urinalysis showed negative for occult blood or protein. The complement levels, partial thromboplastin time, and prothrombin time were within normal ranges. The levels of anticardiolipin and antiphospholipid were normal. Antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and cryoglobulin were negative. Antibodies against syphilis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or human immunodeficiency virus were not detected. Biopsy from subcutaneous nodule showed necrotizing vasculitis of muscular artery with massive cellular infiltrate consisting mostly of polymorphonuclear cells (Fig. 2).

From these findings, a diagnosis of CPAN with vasculitic arterial occlusion of finger was made. She had received prednisolone 60 mg/day and alprostadil infusion. After 2 months, subcutaneous nodules and ulcers on the skin gradually disappeared. But the gangrenous change of the finger progressed, so the finger was amputated. Histologic finding of amputated specimen showed massive fibrinoid necrosis and thrombotic occlusion of the arterial lumen (Fig. 3).

CPAN is a form of necrotizing vasculitis involving small and medium sized arteries. Deep dermal and subcutaneous vessels are predominantly compromised but visceral involvement does not occur (1, 2). Painful subcutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, and ulceration are common features, which are preferentially affecting the lower extremities (2, 4). But necrosis of the finger, as in this case, is a very uncommon finding (9). Several cases of CPAN have been described in Korea, and none of them presented with digital gangrene (10, 11).

The precise etiology of CPAN remains to be unknown. However, an immune mediated mechanism has been postulated. Several infectious and noninfectious conditions have been associated both to initiation and relapse of the disease (2, 5, 7). Among them, streptococcal infection has been commonly implicated (6, 8). Although some evidence of streptococcal infection as an initiating factor for CPAN is present, caution must be exercised when interpreting elevations in the serologic markers of streptococcal infection in the absence of an appropriate clinical presentation. We found the increased ASO level and history of preceding sore throat that might support this hypothesis. Beside Streptococcus, other infectious agent, such as hepatitis viruses (B and C) and Mycobacterium have been implicated in the pathogenesis of CPAN (2, 4).

The characteristic pathologic feature is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis localized at the dermal-pannicular junction. The histopathologic findings can be divided into four stages; degenerative stage with degeneration of arterial wall and deposition of fibrinoid material and partial or complete destruction of internal and external elastic laminae; acute inflammatory stage with an infiltrate mostly composed of neutrophils with some eosinophils around and within the arterial wall; granulation tissue stage with an infiltrate also containing lymphocytes and macrophages and intimal proliferation and thrombosis with occlusion of the lumen leading to ulceration; and healed end-stage with fibroblastic proliferation extending in the perivascular area (4, 12, 13). Immunoglobulin M or C3 deposition in the vessel walls has been found in occasionally. Increased sedimentation rate is the most common laboratory abnormality, whereas other serologic or immunologic markers are not impressive (2).

Because of the favorable course of disease, CPAN usually does not require the intense treatment. Mild forms can be managed with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, salicylates or colchicine. Corticosteroids used in most severe cases (3, 4). If there is no response, immunosuppressive agent such as, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or methotrexate have been used with good responses (2, 4, 14). Stussi et al. (9) described a case of CPAN with digital necrosis, but unlike our case, responded to therapy with prostaglandin I2, calcium channel blocker, and corticosteroid.

CPAN is a benign disease, however, it may a prolonged course with relapses (6). Some cases have been described which had begun with a skin manifestation and progressed to systemic manifestation 19 yr after the onset of the disease (15). Hence, long follow up is essential to exclude systemic involvement.

We present a case of CPAN with digital gangrene as an unusual initial manifestation of CPAN. CPAN should be considered as a causative disease that can lead to gangrene of the digits.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Erythematous nodules on palm and ischemic change of the distal phalanx of the left 4th finger.

References

1. Crowson AN, Mihm MC Jr, Magro CM. Cutaneous vasculitis: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2003. 30:161–173.

2. Daoud MS, Hutton KP, Gibson LE. Cutaneous periarteritis nodosa: a clinicopathological study of 79 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1997. 136:706–713.

3. Gushi A, Hashiguchi T, Fukumaru K, Usuki K, Kanekura T, Kanzaki T. Three cases of polyarteritis nodosa cutanea and a review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2000. 27:778–781.

5. Misago N, Mochizuki Y, Sekiyama-Kodera H, Shirotani M, Suzuki K, Inokuchi A, Narisawa Y. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: therapy and clinical course in four cases. J Dermatol. 2001. 28:719–727.

6. Till SH, Amos RS. Long-term follow-up of juvenile-onset cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa associated with streptococcal infection. Br J Rheumatol. 1997. 36:909–911.

7. Dohmen K, Miyamoto Y, Irie K, Takeshita T, Ishibashi H. Manifestation of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa during interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 2000. 35:789–793.

8. Albornoz MA, Benedetto AV, Korman M, McFall S, Tourtellotte CD, Myers AR. Relapsing cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa associated with streptococcal infections. Int J Dermatol. 1998. 37:664–666.

9. Stussi G, Schneider E, Trueb RM, Seebach JD. Acral necrosis of the fingers as initial manifestation of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. Angiology. 2001. 52:63–67.

10. Yoon CH, Lee CW. Clinical patterns of cutaneous lesions on the legs in patients with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. Korean J Dermatol. 2003. 41:869–872.

11. Bang KT, Herr H, Kim MJ, Lee BH, Bae KW, Kim YC, Chang HK. Three cases with cutaneous polyareritis nodosa. J Korean Rheum Assoc. 2004. 11:447–452.

14. Schartz NE, Alaoui S, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Cordoliani F, Fermand JP, Morel P, Rybojad M. Successful treatment in two cases of steroid-dependent cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa with low-dose methotrexate. Dermatology. 2001. 203:336–338.

15. Dewar CL, Bellamy N. Necrotizing mesenteric vasculitis after long-standing cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. J Rheumatol. 1992. 19:1308–1311.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download