Abstract

Plasma cell granuloma (PCG) of the lung is a rare disease that usually presents as a pulmonary nodule or mass on incidental radiographic examination without symptoms. Although the etiology of PCG is still controversial, many findings have lent support to the lesion being a reactive inflammatory process rather than a neoplastic one. We describe a 53-yr-old male who presented with a hemoptysis and have a lung mass at the left upper lobe on chest radiograph. The lung mass was primarily diagnosed as PCG by percutaneous needle aspiration and biopsy, and the patient was treated with oral steroid because he and relatives refused the operation. However, the size of the lung mass did not change and open thoracotomy and lobectomy were done therefore. He was confirmed as having pulmonary actinomycosis with PCG after surgery. To our knowledge, this is the first report of PCG associated with actinomycosis in Korea.

Plasma cell granuloma (PCG) is uncommon lesion consisting of spindle cells and mononuclear inflammatory cells (1). The lung is the most common site of such lesions, which are frequently detected incidentally on chest radiograph as a solitary lung mass or nodule in asymptomatic patients. Symptomatic patients may complain of cough, chest pain, fever, hemoptysis, and dyspnea (2). PCGs of the lung can occur in any age group, but over half of the patients are less than 40 yr of age. Usually, PCG has been confirmed after surgery for the treatment of lung mass. It most likely represents a non-neoplastic inflammatory reaction to a previous pulmonary infection, but no specific infectious agent has yet been directly linked to PCG (1, 3). Pulmonary actinomycosis is also rare chronic suppurative inflammatory disease that is caused by Actinomyces species.

We herein present an interesting and very rare case of PCG probably associated with pulmonary actinomycosis.

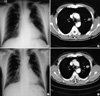

A 53-yr-old male visited the emergency room with hemoptysis of 10 days' duration. He had type II diabetes and had been treated with oral hypoglycemics for one year. He had a personal smoking history of 60 pack years. His vital signs and routine blood tests were nonspecific. Simple chest radiograph and computerized tomography demonstrated a well demarcated 3×2 cm-sized heterogeneous mass with central cavity and peripheral spiculation in the left upper lobe (Fig. 1A, B). The bronchoscopic findings were nonspecific except for the blood clots impacted into the lingular opening. Percutaneous needle aspiration and biopsy were done for tissue diagnosis, and the findings were compatible with PCG (Fig. 2). The patient and relatives refused the operation and he was treated with oral prednisolone at the dose of 1 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks. However, the size of the pulmonary mass did not change after the steroid therapy (Fig. 1C, D). Open thoracotomy and lobectomy were done thereafter. The surgical specimen showed a 2×2.5 cm-sized lesion in the resected left upper lobe that was composed of central solid components with surrounding necrotic and fibrotic tissues. The lesion demonstrated the characteristic sulfur granule peripherally lined with squamous epithelium and the neutrophils. Gomori methenamine silver staining showed lots of dark-stained and rod-shaped Actinomyces (Fig. 3). The peripheries of the specimens obtained by lobectomy was microscopically composed of spindle-shaped cells and inflammatory cells. Immunohistochemical studies of the lung tissues were performed to clarify the nature of the spindle-shaped cells, which were positive for CD68 and negative for muscle specific actin.

The patient was confirmed as having pulmonary actinomycosis with PCG, and he was treated with 20 million units of penicillin G per day for 4 weeks and then oral amoxicillin for 6 months. He completely recovered without any complication.

Actinomycosis is a chronic suppurative infection due to Gram positive, nonspore-forming, anaerobic or microaerophilic bacteria, Actinomyces species (4-7). Although Actinomyces can be a part of the normal oral flora, these are considered to be pathogenic if they invade beyond the mucosal barrier. Pulmonary actinomycosis is a rare condition, but it is an important and challenging diagnosis to make. Even when the clinical suspicion is high, the disease is commonly confused with other chronic suppurative lung diseases and with malignancy (4). Sputum and bronchoscopic diagnostic work up for the pulmonary actinomycosis can not be useful. Tissue diagnosis is usually needed and the sulfur granule needs to be demonstrated. If early diagnosis and treatment with proper antibiotics are established, cure and prevention of serious complications can be achieved.

PCGs of the lung include a spectrum of lesions ranging from benign masses to frankly malignant sarcomas (8). The most consistent pathological feature of these lesions is a background proliferation of spindle cells associated with a variable density of polymorphic infiltrate of mononuclear inflammatory cells. Several findings support a reactive inflammatory process as the most probable pathogenesis rather than a neoplastic process. Consistently with this hypothesis, it has been observed that as many as one third of these lesions have developed after a respiratory infection (2, 9, 10). Most of the infectious organisms that were associated with PCG are uncommon and fastidious. These organisms include Norcardia nova, Mycobacterium malmoense, Elikenella corrodens, Pseudomonas veronii, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (11-15). Previous studies have suggested that the infection-associated PCG is a spindle cell lesion with histocytic or follicular dendritic, rather than a myofibroblastic immunophenotype (16, 17). Consistently with these findings, in this case the immunohistochemical studies of the lung tissues showed that the spindle cells had the phenotype of histiocytes. How an initial infection might develop into PCG is not well understood and no specific infectious agent that directly linked to PCG has yet been.

The association of Actinomyces with plasma cells has been demonstrated in the murine model. The histopathologic features of experimental actinomycotic lesions that were produced in mice by Actinomyces have contained lobulated advancing fronts as well as areas of resolution showing heavy penetration by phagocytic cells, and the main cells involved are polymorphonucleocytes and plasma cells (18).

Radhi et al. reported on a case of a 7-yr-old boy who presented with a retroperitoneal mass which biopsy results showed features consistent with PCG and actinomycosis (7). Dweik et al. suggested that chronic inflammation such as Actinomyces infection might be cause of PCG in a case of pulmonary actinomycosis that presented with what appeared to be a PCG (19).

In our case, fine needle aspiration and biopsy demonstrated that abundant plasma cells, inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, and muscle fibers were mainly observed, which was compatible to the diagnosis of PCG. In addition, the surgical specimen showed typical sulfur granule and Actinomyces on the special staining. These different histologic findings between the find needle biopsy and the surgical resection can be resulted from the inadequate targeting of the approach of the fine needle biopsy, or another suggestion that chronic infection such as Actinomyces infection may be closely associated with PCG. The association of pulmonary actinomycosis with PCG raises the possibility that Actinomyces may be a cause of PCG. Other possibilities may be that the presence of the plasma cells is part of the pathology of pulmonary actinomycosis, or a coincidence.

Although the etiology and pathophysiology of PCG require further investigation, we suggest that a reactive inflammatory process secondary to chronic infection, particularly actinomycosis, may be cause of PCG.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of PCG associated with actinomycosis in Korea.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Chest PA (A) and chest CT (B) at admission demonstrate a well demarcated 3×2 cm-sized heterogeneous mass with central cavity and peripheral spiculation in the left upper lobe. Chest PA (C) and chest CT (D) after one-month steroid treatment show a similar or mildly increased size of the mass. |

| Fig. 2The tissue obtained by percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy shows spindle cells (A) and plasma cells (B) (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×400). |

| Fig. 3(A) The 2×2.5 cm-sized mass in the resected left upper lobe is composed of central solid components with surrounding necrotic and fibrotic tissues. (B) notes the sulfur granule (arrowheads) in the cavity lined with squamous epithelium (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×100). (C) Gomori methenamine silver staining shows a lot of dark-stained and rod-shaped Actinomyces (×400). (D) shows the peripheries of the specimens obtained by needle biopsy and lobectomy, respectively. The microscopic finding consists of spindle-shaped cells and inflammatory cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200). |

References

1. Anthony PP. Inflammatory pseudotumour (plasma cell granuloma) of lung, liver and other organs. Histopathology. 1993. 23:501–503.

2. Kim JH, Cho JH, Park MS, Chung JH, Lee JG, Kim YS, Kim SK, Kim SK, Shin DH, Choi BW, Choe KO, Chang J. Pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor- a report of 28 cases. Korean J Intern Med. 2002. 17:252–258.

3. Matsubara O, Tan-Liu NS, Kenney RM, Mark EJ. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the lung: progression from organizing pneumonia to fibrous histiocytoma or to plasma cell granuloma in 32 cases. Hum Pathol. 1988. 19:807–814.

5. Baik JJ, Lee GL, Yoo CG, Han SK, Shim YS, Kim YW. Pulmonary actinomycosis in Korea. Respirology. 1999. 4:31–35.

6. Tastepe AI, Ulasan NG, Liman ST, Demircan S, Uzar A. Thoracic actinomycosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998. 14:578–583.

7. Radhi J, Hadjis N, Anderson L, Burbridge B, Ali K. Retroperitoneal actinomycosis masquerading as inflammatory pseudotumor. J Pediatr Surg. 1997. 32:618–620.

8. Gal AA, Koss MN, McCarthy WF, Hochholzer L. Prognostic factors in pulmonary fibrohistiocytic lesions. Cancer. 1994. 73:1817–1824.

9. Fiocchi A, Mirri GP, Santini I, Rottoli A, Bernardo L, Riva E. Progression from bronchopneumonia to inflammatory pseudotumor in a seven-year-old girl. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999. 27:138–140.

10. Nonomura A, Mizukami Y, Matsubara F, Shimizu J, Oda M, Watanabe Y, Kamimura R, Takashima T, Kitagawa M. Seven patients with plasma cell granuloma (inflammatory pseudotumor) of the lung, including two with intrabronchial growth: an immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study. Intern Med. 1992. 31:756–765.

11. Azouz S, Bousquet C, Vernhet H, Lesnik A, Senac JP. Pseudotumor form of pulmonary nocardia infection (Nocardia nova) in a renal transplant patient. Rev Mal Respir. 1996. 13:513–515.

12. Yoganathan K, Elliott MW, Moxham J, Yates M, Pozniak AL. Pseudotumour of the lung caused by Mycobacterium malmoense infection in an HIV positive patient. Thorax. 1994. 49:179–180.

13. Lee SH, Fang YC, Luo JP, Kuo HI, Chen HC. Inflammatory pseudotumour associated with chronic persistent Eikenella corrodens infection: a case report and brief review. J Clin Pathol. 2003. 56:868–870.

14. Cheuk W, Woo PC, Yuen KY, Yu PH, Chan JK. Intestinal inflammatory pseudotumour with regional lymph node involvement: identification of a new bacterium as the aetiological agent. J Pathol. 2000. 192:289–292.

15. Park SH, Choe GY, Kim CW, Chi JG, Sung SH. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the lung in a child with mycoplasma pneumonia. J Korean Med Sci. 1990. 5:213–223.

16. Perez-Ordonez B, Rosai J. Follicular dendritic cell tumor: review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1998. 15:144–154.

17. Dehner LP. The enigmatic inflammatory pseudotumours: the current state of our understanding, or misunderstanding. J Pathol. 2000. 192:277–279.

18. Behbehani MJ, Heeley JD, Jordan HV. Comparative histopathology of lesions produced by Actinomyces israelii, Actinomyces naeslundii, and Actinomyces viscosus in mice. Am J Pathol. 1983. 110:267–274.

19. Dweik RA, Goldfarb J, Alexander F, Stillwell PC. Actinomycosis and plasma cell granuloma, coincidence or coexistence: patient report and review of literature. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1997. 36:229–233.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download