Abstract

This study was conducted to evaluate the mid-term results of cervical esophagogastric anastomosis using a side-to-side stapled anastomosis method for treatment of patients with malignant esophageal disease. A total of 13 patients were reviewed retrospectively from January 2001 to November 2005 who underwent total esophagectomy through a right thoracotomy, gastric tube formation through a midline laparotomy and finally a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. Average patient age was 62.6 yr old and the male to female ratio was 11:2. The mean anastomosis time was measured to be about 32.5 min; all patients were followed for about 22.8±9.9 months postoperatively. There were no early or late mortalities. There were no complications of anastomosis site leakage or conduit necrosis. A mild anastomotic stricture was noted in one patient, and required two endoscopic bougination procedures at postoperative 4th month. Construction of a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis by side-to-side stapled anastomosis is relatively easy to apply and can be performed in a timely manner. Follow up outcomes are very good. We, therefore, suggest that the side-to-side stapled anastomosis could be used as a safe and effective option for cervical esophagogastric anastomosis.

Because early complications such as anastomosis site leakage can be disastrous and cause significant morbidity and mortality to patients undergoing esophageal reconstruction, the successful esophagogastric anastomosis is closely related to early patient outcome (1). Cervical esophagogastric anastomosis (CEGA) is a widely accepted procedure despite criticisms from some authors (2-4). Many surgeons prefer this technique due to better tumor eradication, and reduced morbidity and mortality associated with anastomotic breakdown (1, 5, 6) despite known risks of leakage, stricture formation and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury (3, 7, 8). Currently, CEGA is becoming an increasingly common procedure (9).

CEGA consists partly of a hand-sewn procedure and partly of a method that employs mechanical suturing devices. Although there has been one prospective randomized trial advocating the hand-sewn technique in fashioning cervical esophagogastric anastomoses (10), there are disagreements in the literature (11). Kim and colleagues (12) and Orringer and associates (9) have reported the usefulness of endo-GIA stapler devices in esophago-enteric anastomosis. Orringer and associates (9) introduced the CEGA technique incorporating both the hand sewn technique and that using endo-GIA (side-to-side stapled anastomosis); this method has been reported to reduce the incidence of anastomosis related complications.

In this study, we evaluated the mid-term results of CEGA using side-to-side stapled anastomosis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Retrospective medical records review was conducted for 13 of 18 patients who underwent esophagogastrostomy from January 2001 to November 2005. All 13 patients were diagnosed with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and underwent curative CEGA. Patients diagnosed with non-squamous cell carcinoma, who underwent palliative surgery, or thoracic esophagogastrostomy were excluded from the study. The male to female ratio was 11:2 with an average age of 62.6 yr (47-79 yr). The most common presenting symptom was dysphagia, and chest pain. Tumor location was diverse; 8 patients had midthoracic esophageal tumors, 2 patients had tumors in the upper thoracic esophagus, 1 patient had lower thoracic esophageal carcinoma, and 2 patients had dual locations (upper and mid thoracic esophagus, and mid and lower thoracic esophagus, respectively) The two patients diagnosed with dual esophageal cancer had celiac lymph node metastasis and was diagnosed as stage IVB (Table 1).

All patients underwent diagnostic and metastatic workup under a preset protocol including endoscopy with endoscopic ultrasonography, upper gastrointestinal series with or without colon studies, CT scans (neck, chest, and abdomen), bone scan, optional brain CT, and optional PET-CT. After such evaluation, the patients were grouped into according to the presence or absence of distant metastasis; M0 group-immediate surgery, M1 group-neoadjuvant chemo- or radiotherapy before surgery. The two pati- ents in the M1 group received neoadjuvant chemotherapy before operation.

The operative technique consisted of a total thoracic esophagectomy with mediastinal lymphadenectomy via a right thoracotomy and gastric tube construction via a midline laparotomy incision with preservation of the right gastroepiploic artery. Celiac lymph node dissection was also conducted during the laparotomy phase. Gastric drainage procedures were performed in all patients; Heller's pyloromyotomy (4 patients), pylorus fracture by manipulation (9 patients). The gastric tube was pulled up through the posterior mediastinum to the left cervical area for side-to-side CEGA. CEGA was performed according to the method introduced by Orringer and colleagues (9). Their technique recommends a side-to-side anastomosis with an endo-GIA 30 mm stapler on the anterior stomach wall. The endo-GIA II 30-3.5 mm stapler (Autosuture®, Norwalk, CT, U.S.A.) was used in the first phase of the CEGA, with care taken to avoid involvement of the conduit tip. The second phase of the CEGA, the anterior closure of the anastomosis site contained within the hood of the overlying esophagus, was performed by a hand-sewn method using Vicryl 5-0 (Ethicon®, Piscateway, NJ, U.S.A.) in interrupted sutures. In patients showing no cervical lymph node metastasis on neck CT (all of the patients in this study), cervical lymph node dissection was not performed.

Postoperative esophagography was performed on the 7th postoperative day to evaluate functional results and to identify anastomosis site complications. All patients received endoscopic examination 2 months after surgery (Fig. 1); neck, chest, and abdominal CT scans were performed routinely 6 months after the operation.

The mean operation time was 10.7 hr with a mean anastomosis tome of 32.5 min. All patients received mechanical ventilation during the immediate postoperative period for an average of 15.2 hr to reduce pulmonary complications. Postoperative intensive care unit stay was 61.2±20.5 hr.

The mean hospital stay was 33.3 days and patients were followed up for 22.8±9.9 months postoperatively. There were no early or late mortalities related to the procedure. We experienced no respiratory or cardiovascular complications throughout this study. Two patients complained of postoperative voice hoarseness and intermittent episodes of aspiration. Laryngoscopic evaluation revealed vocal cord palsies, but these were transient symptoms and both patients recovered fully by 2 months after surgery.

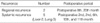

There were no cases of anastomosis site leakage or conduit necrosis. A mild anastomosis site stricture was noted in one patient and he received two endoscopic bougienations four months after surgery. Postoperative staging and operative data are summarized in Table 1.

Cancer recurrences were noted in 7 patients (Table 2) during follow up. Two patients confirmed with regional recurrences had mediastinal and celiac lymph node metastases.

Esophageal anastomosis site complications are important causes of postoperative morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy. Cervical esophagogastric anastomosis is preferred by many surgeons because of larger resection margins and less dangerous anastomosis leakage (5, 6), although it has an increased risk for recurrent laryngeal nerve injury (8).

Anastomosis techniques, both the hand-sewn and mechanical stapling procedures, have been evaluated by many investigators. Gandhi and Naunheim (13) reported a 5-26% incidence of anastomosis leak, and 10-15% incidence of benign anastomosis site strictures after hand-sewn CEGA. In another study, Fok and associates (14) reported a 5% incidence of anastomosis leakage in hand-sewn CEGA versus a 3.8% incidence in a group using a circular stapler for gatro-enteric anastomosis. However, a greater number of stapled anastomoses resulted in strictures. In general, stapled anastomosis is a safe and effective technique (15-18).

Although Hsu and colleagues (19) reported that the circular stapler is a feasible option for CEGA, the application of these devices in the cervical region is technically complicated (10, 11). Many investigator, therefore, discourage the use of circular stapling devices (10). Kim et al. (12) and Orringer et al. (9) have reported on the usefulness of Endo-GIA 30 mm stapler in CEGA. They found that Endo-GIA was easy to handle in the cervical region and with a generous 3 cm anastomosis there was a reduction in anastomosis site stricture and postoperative dysphagia compared to circular staplers. Also, anastomosis leak was uncommon.

Collard and associates (20) have reported on a side-to-side stapled CEGA with an Endo-GIA stapler using the tip of the mobilized stomach. This, in effect, creates a functional end-to-end esophagogastric connection. Orringer and colleagues report that gastroesophageal refulx was less common when the anastomosis is performed using the anterior wall of the stomach. We conducted CEGA according to Orringer's method and confirmed the benefits of this approach. The CEGA technique was associated with gastric conduit tip necrosis, a rare but very serious problem (4, 9). Fortunately, we did not experience any cases of graft failure or conduit tip necrosis in our study.

Although Orringer's technique requires manual sewing in the final anterior closure of the CEGA, this did not increase leakage rates after esophageal resection of squamous cell carcinomas. The benign stricture rate, surgical outcome and long-term results were satisfactory. In conclusion, side-to-side stapled anastomosis according to the technique introduced by Orringer and colleagues is the preferred procedure for CEGA because it is relatively easy to perform and therefore less operator dependent, and requires less time to perform hand sewn method (11).

Figures and Tables

References

1. Urschel JD. Esophagogastrostomy anastomotic leaks complicating esophagectomy: a review. Am J Surg. 1995. 169:634–640.

2. Lam TC, Fok M, Cheng SW, Wong J. Anastomotic complications after esophagectomy for cancer. A comparison of neck and chest anastomoses. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992. 104:395–400.

3. Chasseray VM, Kiroff GK, Buard JL, Launois B. Cervical or thoracic anastomosis for esophagectomy for carcinoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989. 169:55–62.

4. Iannettoni MD, Whyte RI, Orringer MB. Catastrophic complications of the cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995. 110:1493–1500.

5. Muller JM, Erasmi H, Stelzner M, Zieren U, Pichlmaier H. Surgical therapy of oesophageal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1990. 77:845–857.

6. Patil PK, Patel SG, Mistry RC, Deshpande RK, Desai PB. Cancer of the esophagus: esophagogastric anastomotic leak--a retrospective study of predisposing factors. J Surg Oncol. 1992. 49:163–167.

7. Dewar L, Gelfand G, Finley RJ, Evans K, Inculet R, Nelems B. Factors affecting cervical anastomotic leak and stricture formation following esophagogastrectomy and gastric tube interposition. Am J Surg. 1992. 163:484–489.

8. Fok M, Law S, Stipa F, Cheng S, Wong J. A comparison of transhiatal and transthoracic resection for oesophageal carcinoma. Endoscopy. 1993. 25:660–663.

9. Orringer MB, Marshall B, Iannettoni MD. Eliminating the cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leak with a side-to-side stapled anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000. 119:277–288.

10. Laterza E, de' Manzoni G, Veraldi GF, Guglielmi A, Tedesco P, Cordiano C. Manual compared with mechanical cervical oesophagogastric anastomosis: a randomised trial. Eur J Surg. 1999. 165:1051–1054.

11. Urschel JD, Blewett CJ, Bennett WF, Miller JD, Young JE. Hand-sewn or stapled esophagogastric anastomoses after esophagectomy for cancer: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dis Esophagus. 2001. 14:212–217.

12. Kim IH, Kim KT, Park SM, Lee SY, Baek MJ, Sun K, Kim HM, Lee IS. Cervical esophago-enteric anastomosis with straight endostapler. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999. 32:924–929.

13. Gandhi SK, Naunheim KS. Complications of transhiatal esophagectomy. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1997. 7:601–610.

14. Fok M, Ah-Chong AK, Cheng SW, Wong J. Comparison of a single layer continuous hand-sewn method and circular stapling in 580 oesophageal anastomoses. Br J Surg. 1991. 78:342–345.

15. Law S, Fok M, Chu KM, Wong J. Comparison of hand-sewn and stapled esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal resection for cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 1997. 226:169–173.

16. Beitler AL, Urschel JD. Comparison of stapled and hand-sewn esophagogastric anastomoses. Am J Surg. 1998. 175:337–340.

17. Honkoop P, Siersema PD, Tilanus HW, Stassen LP, Hop WC, van Blankenstein M. Benign anastomotic strictures after transhiatal esophagectomy and cervical esophagogastrostomy: risk factors and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996. 111:1141–1146.

18. Wong J, Cheung H, Lui R, Fan YW, Smith A, Siu KF. Esophagogastric anastomosis performed with a stapler: the occurrence of leakage and stricture. Surgery. 1987. 101:408–415.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download