Abstract

This study evaluated the prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections in Korea. Pooled estimates of the anti-HCV positivity were calculated using the data published in 15 reports on the general population and health check-up examinees. The overall pooled estimate of the prevalence of HCV among middle-aged adults (40 yr old and above) was 1.68% (95% confidence interval: 1.51-1.86%) during the year of 1990-2000 among the general population. Most of the published data indicated that the prevalence of anti-HCV increased with age. The anti-HCV positivity was significantly higher in females than in males. Because the risk of HCV exposure in blood recipients has decreased remarkably, the spread of HCV through means other than a transfusion must be prevented.

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and hepatitis B virus (HBV) are the leading causes of chronic liver disease and liver cancer in Korea. Many studies on the prevalence of HBV or HCV infection have been performed using non-representative samples or small samples from a selected population. Regarding the prevalence of the HBV, the National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHNS) in 1998 included some serologic markers for HBV infection (1). Unfortunately, there is no population-based serologic study that has estimated the prevalence of a HCV infection. In this study, we investigated the pooled estimates of HCV prevalence using data from 15 reports. In recent years, the pooled-analysis using published reports has been increasing for epidemiological study (2).

Publications on the HCV antibody and its relationship with epidemiology (prevalence, risk factors) were obtained from PubMed and KoreaMed (www.pubmed.gov and www.koreamed.org) (1990-2004) and by checking the reference lists to find other reports. These reports cover the prevalence of anti-HCV in the general population, the distribution of risk factors, and the transmission route of the HCV infection. Reference lists of publications were examined to identify studies. The data from 15 reports were included in this paper. These reports had more than 500 subjects and the number of subjects that were positive for HCV according to age and gender were listed.

The following information was extracted: the study area, study year, method of the anti-HCV test, the distribution of study subjects according to age and gender (if available) from 15 reports on the general population (Table 2).

We studied 146,561 subjects from 15 publications and 1,275 subjects were positive for HCV. HCV prevalence was estimated by multiple logistic regression analysis and is expressed as a percentage according to age and gender. The HCV prevalence by time and age was estimated with the model, logit (p)=β0+β1 time+β2 age, where p is probability that the subject was positive for HCV, time variable was categorized by 1990-1994, 1995-2000 and age variable was categorized by 40-49, 50-59, 60+ yr. The HCV prevalence by time and gender was estimated with the model logit (p)=β0+β1 time+β2 gender, where gender variable was categorized by male and female.

The pooled estimates of the prevalence of HCV were calculated as a truncated prevalence among adults 40 yr and older due to the rarity of cases in those under 40 yr of age. The pooled estimates were calculated by standardizing the estimated HCV prevalence in the Korean population (Resident registration population from Korea National Statistical Office) by time and age.

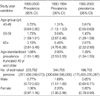

In the 1990s, the overall anti-HCV prevalence was approximately 0.68-3.54% among health check-up middle-aged examinees (age 40 yr and over) and 0.42-1.45% among healthy people with a normal ALT level (Table 1). In the pooled analysis, the age-standardized prevalence truncated to those 40 yr and older was 1.68% (95% CI 1.51-1.86) (Table 3). During 1990-1994, the prevalence was 2.90% (95% CI 2.53-3.33), and was different from 1.39% (95% CI: 1.24-1.55) during 1995-2000. Some of the published data showed that the prevalence of anti-HCV in males was similar to that in females. However, a pooled estimate of the HCV prevalence in males (0.77%, 95% CI: 0.72-0.83) was significantly lower than in females (1.06%, 95% CI: 0.97-1.16) (Table 3).

The important goal of this study was to calculate a quantitative pooled estimate of the prevalence of HCV. Even though there were limitations in the publication bias and the heterogeneity between the studies in the pooled-analysis, our estimates of the prevalence are believed to be conservative.

The overall HBsAg prevalence was 5% in the NHNS (Korea National Health & Nutrition Survey, 2002). HBV is by far a more important risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea. A HCV infection shows a stronger association with hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients (3). In Korea, the surveillance program for anti-HCV positive people 40 yr and older was introduced by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the National Cancer Center in 2003.

There are few papers that have reported the prevalence among children and young adults. The prevalence of anti-HCV in children (6-11 yr old) was 0.81% (17/2,080) in Seoul in 1995 (4) and 0.4% (5/1,350) among young adults (16-24 yr old) (5).

Most HCV infected persons in Korea are elderly. However, more attention should be paid to whether new infections occur in groups besides the elderly. Some of the published data showed a similar prevalence of the anti-HCV in males and females, but two reports indicated that the anti-HCV prevalence among females was higher than that among males in the rural population (6, 7). These two reports are from the same area. Therefore, the regional variation in the prevalence of the HCV should be clarified in future studies.

Most of the published data showed that the frequency of anti-HCV increased with age. The high prevalence of anti-HCV among older persons is most likely due to a cohort effect of the risk of acquiring a HCV infection being higher in the distant past than currently. Because HCV is rarely transmitted by a blood transfusion in Korea since the introduction of the HCV antibody test to screen blood donors (April 1991), the risk of HCV exposure among blood recipients has decreased. Therefore, an evaluation of the behavioral risk factors other than blood transfusions is important in terms of the transmission of the HCV infection.

Although the anti-HCV positive prevalence has reduced in recent years, the HCV RNA positive rates must be closely monitored in the future to determine the actual risk of HCV infection and further study for reduction of the anti-HCV positive prevalence is needed.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Studies of the prevalence of anti-HCV among the general population or health examinees in Korea during 1992-2003

References

1. Blettner M, Sauerbrei W, Schlehofer B, Scheuchenpflug T, Friedenreich C. Traditional reviews, meta-analyses and pooled analyses in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1999. 28:1–9.

2. Lee DH, Kim JH, Nam JJ, Kim HR, Shin HR. Epidemiological findings of hepatitis B infection based on 1998 National Health and Nutrition Survey in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2002. 17:457–462.

3. Lee HS, Han CJ, Kim CY. Predominant etiologic association of hepatitis C virus with hepatocellular carcinoma compared with hepatitis B virus in elderly patients in a hepatitis B-endemic area. Cancer. 1993. 72:2564–2567.

4. Lee JM, Yoo HS, Jang UK, Kim DJ, Kim YB, Kim HY, Park CK, Yoo JY. The prevalence of anti-HCV positivity in healthy Korean children. Korean J Hepatol. 1996. 2:160–165.

5. Ju YH, Shin HR, Oh JK, Kim DI, Lee DH, Kim BK, Kim JI, Jung KY. A seroepidemiological study of hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV) infection in the young population in parts of Busan, Korea. Korean J Prev Med Public Health. 2004. 37:253–259.

6. Shin HR, Kim JY, Ohno T, Cao K, Mizokami M, Risch H, Kim SR. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus infection among Koreans in rural area of Korea. Hepatol Res. 2000. 17:185–196.

7. Shin HR, Kim JY, Kim JI, Lee DH, Yoo KY, Lee DS, Franceschi S. Hepatitis B and C virus prevalence in a rural area of South Korea: the role of acupuncture. Br J Cancer. 2002. 87:314–318.

8. Shin KK, Yoon JD, Yoo JC, Kim MB, Kim KS, Suh SD. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibody in Korea. J Korean Soc Virol. 1993. 23:203–214.

9. Kim YS, Pai CH, Chi HS, Kim DW, Min YI, Ahn YO. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibody among Korean adults. J Korean Med Sci. 1992. 7:333–336.

10. Oh W. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis C virus among middle-aged men. Clin Path Qual Assur. 1993. 15:229–235.

11. Yoon DK, Cho KW, Hong MH, Kwon SY, Byun KS, Lee CH. Prevalence of antibody to hepatitis C virus in Korean adults. Korean J Infect Dis. 1994. 26:237–247.

12. Seo TS, Lee SS. A study on positive rate of HBsAg, HBsAb and anti-HCV in Korean adults. Korean J Blood Transfus. 1998. 9:259–272.

13. Han SW, Park YU, Kim SM, Shin DH, Seo SP, Ryang DW, Kim SJ. A study on positive rate of anti-HCV in Korean adults. Korean J Med. 1994. 47:744–749.

14. Kim MS, Seo KS, Kim NJ, Choi SK, Suh SP, Choi JS, Kim SJ. A study on the positivities of anti-HCV by second-generation ELISA in rural area of Chonnam Province. Korean J Med. 1997. 53:741–746.

15. Na HY, Park MH, Park KS, Sohn YH, Joo YE, Kim SJ. Geographic characteristics of positivity of anti-HCV and Chonnam Province: Survey data of 6,790 health screenees. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2001. 38:177–184.

16. Park KS, Lee YS, Lee SG, Hwang JY, Chung WJ, Cho KB, Hwang JS, Ahn SH, Park SK. A study on markers of viral hepatitis in adults living in Daegu and Gyungbuk area. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2003. 41:473–479.

17. Kim WS, Dam DO, Shin HR, Jung KY, Kim JY. Epidemiologic study of hepatitis B and C among adults in Pusan. J Pusan Med Assoc. 1995. 31:18–28.

18. Shin HR, Kim JY, Jung KY, Kim WS, Hong YS, Kim BK, Kim SR, Lee BO, Park TS, Lee YH, Ok ID, Ryan MK, Taniguchi M, Kim MM, Kim KI. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infection among adults in Korea. Hepatol Res. 1997. 7:213–225.

19. Jung JI, Sohn SH, Cho WH, Jung JH, Kim YL, Lee JK. Prevalence of anti-HCV in healthy subjects in Ulsan area. Korean J Med. 1993. 45:322–327.

20. Jeong TH, Jeon TH. PCR prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus infection in the adult population of Ulsan. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 1998. 19:364–373.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download