Abstract

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) plays an important role in immune defense. This study was undertaken to investigate the association between hepatitis B virus infection and polymorphisms of MBL gene. We assessed the single nucleotide polymorphism at codon 54 in exon 1 of MBL in patients with hepatitis B virus infection and HBsAg negative controls in Korean population. A total of 498 enrolled subjects was classified into four groups. Group 1; Clearance, Group 2; Inactive healthy carrier, Group 3; Chronic hepatitis, Group 4; Liver cirrhosis. MBL gene polymorphisms at codon 54 led to three genotypes (G/G, G/A, A/A). When we divided subjects into clearance group (group 1) and persistence group (group 2-4), G/G genotype and A-allele carrier were observed in 55.6% and 44.4% in clearance group, 64.8% and 35.2% in persistence group (p=0.081), respectively. When hepatitis B virus persistent cases were divided into inactive healthy carrier (group 2) and disease progression group (group 3 and 4), MBL gene polymorphisms at codon 54 were not related to disease progression (p=0.166). MBL gene polymorphism at codon 54 was not associated with the clearance of hepatitis B virus infection nor progression of disease in chronic hepatitis B virus infection.

Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) may result in various conditions ranging from inactive healthy carrier to chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and sometimes may progress to hepatocellular carcinoma (1). The reasons for this variation in the natural history of HBV infection are unknown but are probably related to host immune factors. Chronic infection develops in approximately 5% of immunocompetent adults, but up to 90% of newborns may become HBV carriers if the mothers are seropositive for hepatitis B virus e antigen (HBeAg). In hepatitis endemic area such as China and Korea, vertical transmission is the most important cause of hepatitis B persistence (2), but this cannot completely explain the persistence of HBV infection.

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) is an acute-phase protein involved in activation of the classical complement pathway (3). MBL acts as a direct opsonin by binding to collectin receptors through its collagen domain (4). The middle surface protein of the HBV envelope contains a mannose-rich oligosaccharide to which MBL could bind (5). MBL is an important component of the human innate immune system and may play a role in HBV infection.

To date three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been well characterized in exon 1 at codons 52 (CGT→TGT), codon 54 (GGC→GAC) and codon 57 (GGA→GAA), and these differ considerably in their frequencies in different populations (6). It is well known that MBL gene mutation leads to low serum MBL level, which in turn makes affected individuals more prone to infection. SNPs in codon 54 and 57 of the MBL gene are related to low serum MBL levels (7). Several investigators reported the association between MBL gene polymorphism and HBV or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (8-11). However, reports concerning the role of MBL in HBV infections are conflicting. Furthermore, there are no data available regarding the prevalence of MBL gene SNPs in the Korean population and the role of these SNPs in the natural course of HBV infection.

Therefore, we have investigated the genotype frequencies at codon 54 in the coding region of the MBL gene in Korean patients with chronic hepatitis B, liver cirrhosis, and who recovered infection, and have tried to find any association between MBL gene SNPs and natural history of HBV infection.

Between March 2002 and September 2002, a total of 498 subjects was enrolled prospectively, from out-patient clinic of the Gastroenterology Department of Ajou University Hospital, Suwon, Korea. They were classified into four groups according to the various status of HBV infection. Group 1; HBV Clearance group [n=126, HBsAg (-), AntiHBc (+), AntiHBs (+), who recovered from HBV infection], Group 2; Inactive healthy carrier group [n=58, HBsAg (+) and HBeAg (-), sustained normal transaminase level], Group 3; Chronic hepatitis [n=239, HBsAg (+), elevated transaminase (≥2 times the upper limit of normal at least one time during the follow-up period], Group 4; Liver cirrhosis [n=75, typical morphologic findings on computed tomography/ultrasound and corresponding laboratory features or evidence of portal hypertension]. Among them, group 2, 3 and 4 were classified into "HBV persistence group".

The diagnostic criteria for chronic HBV infection were seropositivity for HBsAg for more than 6 months, seronegativity for anti-HBs and presence of anti-HBc, and were followed up for disease progression. Inactive healthy carrier and chronic hepatitis patients had no evidence of portal hypertension and/or liver cirrhosis. None of enrolled patients had hepatocellular carcinoma. The chronic hepatitis (group 3) and liver cirrhosis patients (group 4) were considered to have chronic progressive liver disease, classified as "progressive group" when compared with inactive healthy carriers (group 2).

Patients who were positive for anti-HBs and negative for anti-HBc IgG (vaccinated subjects), and patients with other types of chronic liver disease such as alcoholic liver disease, chronic hepatitis C, steatohepatitis, Wilson's disease, were excluded from this study. All the subjects were Korean, a single ethnic population. Informed consents were obtained from each subject, and the Institutional Review Board of Human Research of Ajou University Hospital approved the study protocol.

Before the analysis, we tested MBL gene polymorphism at codon 52, 54 and 57 in 100 healthy Korean populations. In this pilot assay, we could not find any polymorphism at codon 52 and codon 57 in Korean population. The only MBL gene SNP found in our Korean population was that at codon 54 of exon 1. MBL gene polymorphism was identified only at codon 54 (Glycine→Aspartate, GGC→GAC), leading to three genotype (G/G, G/A, A/A genotype). Therefore, we assessed the genetic polymorphism at codon 54 of MBL in 372 patients with HBV infection, and in 126 HBsAg negative controls who had eliminated HBV.

Genomic DNA was extracted from 300 µL whole blood using a DNA Purification kit (GENTRA, Minneapolis, MN, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The SNP of MBL gene codon 54 was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. The parameters for thermocycling were as follows: An initial activation step of 95℃ for 10 min preceded the cycling program; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95℃; annealing at 72℃ for 1 min; and final extension at 72℃ for 7 min. Each PCR products were purified by a Qiagen PCR purification kit, and the polymorphisms were detected by single base primer extension assay (SNP IT™). Briefly, the assay is to anneal a detection primer to the nucleic acid sequence immediately 3' of the nucleotide position to be analyzed and to extend this primer with a single labeled nucleoside triphosphate that is complementary to the nucleotide to be detected using a DNA polymerase.

For univariate analysis, χ2 test was used for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium of alleles at MBL gene loci and independent sample t test for normally distributed continuous variables. The analysis was carried out using the statistical computer software SPSS11.0/Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). All p values were two-tailed, and p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance throughout the study.

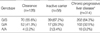

Demographic characteristics of the subjects with HBV clearance vs. persistence groups and inactive carrier vs. progression groups, were shown in Table 1. Differences between clearance and persistence groups in aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase (AST/ALT), platelet, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) were observed. The serum levels of AST, ALT, AFP at baseline were significantly higher in HBV persistence group. The platelet count was lower in HBV persistence group. Age was younger in persistence group, but no significant differences in the distributions of their gender were detected between clearance group and persistence group. Concerning the comparison of inactive carrier and HBV progression group, male sex was the risk factor for HBV progression, but there was no difference in age distribution.

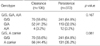

Genotype data were complete for the MBL gene markers in all of the subjects. The frequencies of the genotypes of the MBL codon 54 in enrolled patients are summarized in Table 2. Allelic frequencies in codon 54 of MBL gene are as follows. In group 1, G/G genotype was 55.6% of patients, G/A genotype was 41.3%, A/A genotype was 3.2%. In group 2, G/G, G/A, A/A genotype frequencies were 67.2%, 29.3% and 3.4%, respectively. In group 3, G/G, G/A, A/A genotype frequencies were 63.6%, 32.6% and 3.8%, respectively. In group 4, G/G, G/A, A/A genotype frequencies were 66.7%, 32.0% and 1.3%.

MBL gene SNPs at codon 54 were analyzed in patients with chronic HBV infection ("persistence") and healthy individuals who recovered from HBV infection ("clearance") (Table 3). Since specific MBL genotype has been linked to MBL protein production and phenotype, we repeated the analysis of data comparing G/G genotype and A-allele carrier among the different groups. The frequencies of G/G genotype and A-allele carrier (G/A, A/A) were observed in 55.6% and 44.4% in HBV clearance group, 64.8% and 35.2% in persistence group. Comparison of genotype frequencies showed no significant differences between the clearance and persistence group (p=0.081).

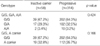

We evaluated whether MBL gene polymorphism is related to disease progression in HBV infection by comparing the genotype frequency between inactive carriers (group 2) and progressive group (group 3 and 4). No significant differences were detected between two groups in the distributions of MBL gene genotype at codon 54 (G/G:67.2%, A allele carrier:32.8% in HBV healthy carrier, G/G:64.3%, A-carrier:35.7% in HBV progression group) (p=0.166) (Table 4).

The persistent HBV infection is a major public health problem, particularly in the hepatitis endemic areas such as Korea, Taiwan and China (12). Elimination of HBV after infection depends on the activities of the patients' immune systems. It is well established that several host factors, including age at the time of infection, sex, immune status and possibly ethnic origin, are important in promoting development of chronic hepatitis B infection. These factors may have confounding impacts on this study. The family history of HBV infection was not completely evaluated and it was hard to presume the onset of HBV infection. Therefore, we were not able to compare the effect of the polymorphism on the risk for chronic HBV infection to that of the age at which the subject is infected. However, considering the finding that perinatal or early childhood infections of HBV, particularly mother-to-child transmission of the virus, is the most common source of chronic infection in the endemic area, most HBV persistent subjects in this study are considered to be infected in this manner. Moreover, our study included single ethnic population. Therefore, we have minimized the confounding factors affecting the course of HBV infection.

The host genetic factors involving genetic polymorphisms are reported to play a key role in influencing clinical outcomes of infectious disease. A number of studies have identified polymorphisms that influence susceptibility to persistent HBV infection (9, 13, 14). Previous reports suggest that DRB1*1301 and *1302 allele are both protective against development of chronic HBV infection (15). A protective effect of DRB1*1301, *1302 against the development of HBV persistence has been suggested in a study on an ethnically heterogeneous group of west Africans (13). Cytokine polymorphisms such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) or interleukin-10 (IL-10) were investigated. Recently, Kim et al. reported that TNF-α promoter allele associated with higher-plasma TNF-α levels was strongly associated with the resolution of HBV infection in Korean population (14).

MBL is a Ca2+ dependent serum lectin specific for mannose and N-acetylglucosamine (4). MBL has been known to have an important role in innate immunity and has been shown to have complement dependent bactericidal activity (3). The middle envelope protein of HBV has an asparagine residue at position 4. This residue is glycosylated with an oligosaccharide, which is, in part, mannose-terminated. Therefore, opsonization of viral particle by normal serum MBL is possible.

MBL serum levels are profoundly reduced by polymorphisms in the coding region of the MBL gene (7). Concerning the relationship between natural history of HBV infection and MBL gene SNPs, many reports showed conflicting results. Yuen et al. showed that codon 54 mutation of MBL gene was associated with progression of disease in chronic hepatitis B infection in Chinese population. According to their reports, in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, the codon 54 mutation rate was greatly increased. And they found that spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) patients had marked increase in codon 54 mutation rate and decrease in serum MBL level when compared with those without SBP (8). In Caucasian population, mutant allele at codon 52 of MBL gene was reported to be associated with chronic hepatitis B infection. But, they failed to reveal the association between SNP at codon 52 and HBV persistence in Asian population. Furthermore, there was no association of the codon 54 or codon 57 mutant alleles with acute or chronic hepatitis B (11). Therefore, the role of MBL in the outcome of HBV infection still remains unclear.

Our study demonstrated that the SNP at the second position of codon 54 of MBL was not associated with HBV persistence. This result was consistent with the previous report, which showed that this polymorphism have no association with HBV clearance (16). We included more than 100 individuals who were completely recovered from HBV infection as control. Furthermore, we believe that the controls in our study were more relevant to evaluate the role of host genetic factor in determining viral clearance of HBV.

We found no association of MBL gene SNP at codon 54 with disease progression. There are a few studies suggesting the relationship of the polymorphism with the disease progression of HBV infection (8). In the present study, the number of subjects with A/A genotypes at codon 54 of MBL gene was limited, so we had difficulty in assessing any possible association between the genotypes and clinical features. Such ethnic differences in the distribution of the polymorphisms may account for the lack of the correlation in our study, which was not in agreement with other studies. In addition, the number of the patients who undergone liver biopsy during the study period was limited in the study so that we might under- or overestimate the stage of disease progression in some of patients with chronic HBV infection. It might miss possible association between the polymorphisms and disease progression in HBV infection.

Although several studies have suggested that the MBL gene SNP alter MBL production, it was mostly based on in vitro experiments. The results would be different according to the type of the stimuli or experimental conditions. MBL expression may also be disease stage-specific, and serum levels may not necessarily correlate with the local MBL levels in liver. Further studies are needed to evaluate the exact functional consequences of MBL polymorphisms on MBL level in both peripheral blood and liver cells at various stages of disease progression.

In conclusion, this study suggested that polymorphism at codon 54 of MBL gene is not associated with HBV clearance nor disease progression in Korean population. Further studies should continue to address the effect of these polymorphisms on HBV infection.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Hoofnagle JH, di Bisceglie AM. The treatment of chronic viral hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1997. 336:347–356.

2. Lai CL, Lok AS, Lin HJ, Wu PC, Yeoh EK, Yeung CY. Placebo-controlled trial of recombinant alpha 2-interferon in Chinese HBsAg-carrier children. Lancet. 1987. 2:877–880.

3. Matsushita M, Fujita T. Activation of the classical complement pathway by mannose-binding protein in association with a novel C1s-like serine protease. J Exp Med. 1992. 176:1497–1502.

4. Ikeda K, Sannoh T, Kawasaki N, Kawasaki T, Yamashina I. Serum lectin with known structure activates complement through the classical pathway. J Biol Chem. 1987. 262:7451–7454.

5. Gerlich WH, Lu X, Heermann KH. Studies on the attachment and penetration of hepatitis B virus. J Hepatol. 1993. 17:Suppl 3. S10–S14.

6. Lipscombe RJ, Sumiya M, Hill AV, Lau YL, Levinsky RJ, Summerfield JA, Turner MW. High frequencies in African and non-African populations of independent mutations in the mannose binding protein gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1992. 1:709–715.

7. Madsen HO, Garred P, Thiel S, Kurtzhals JA, Lamm LU, Ryder LP, Svejgaard A. Interplay between promoter and structural gene variants control basal serum level of mannan-binding protein. J Immunol. 1995. 155:3013–3020.

8. Yuen MF, Lau CS, Lau YL, Wong WM, Cheng CC, Lai CL. Mannose binding lectin gene mutations are associated with progression of liver disease in chronic hepatitis B infection. Hepatology. 1999. 29:1248–1251.

9. Song le H, Binh VQ, Duy DN, Juliger S, Bock TC, Luty AJ, Kremsner PG, Kun JF. Mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphisms and hepatitis B virus infection in Vietnamese patients. Mutat Res. 2003. 522:119–125.

10. Matsushita M, Hijikata M, Ohta Y, Iwata K, Matsumoto M, Nakao K, Kanai K, Yoshida N, Baba K, Mishiro S. Hepatitis C virus infection and mutations of mannose-binding lectin gene MBL. Arch Virol. 1998. 143:645–651.

11. Thomas HC, Foster GR, Sumiya M, McIntosh D, Jack DL, Turner MW, Summerfield JA. Mutation of gene of mannose-binding protein associated with chronic hepatitis B viral infection. Lancet. 1996. 348:1417–1419.

12. Stevens CE, Beasley RP, Tsui J, Lee WC. Vertical transmission of hepatitis B antigen in Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 1975. 292:771–774.

13. Thursz MR, Kwiatkowski D, Allsopp CE, Greenwood BM, Thomas HC, Hill AV. Association between an MHC class II allele and clearance of hepatitis B virus in the Gambia. N Engl J Med. 1995. 332:1065–1069.

14. Kim YJ, Lee HS, Yoon JH, Kim CY, Park MH, Kim LH, Park BL, Shin HD. Association of TNF-alpha promoter polymorphisms with the clearance of hepatitis B virus infection. Hum Mol Genet. 2003. 12:2541–2546.

15. Hohler T, Gerken G, Notghi A, Lubjuhn R, Taheri H, Protzer U, Lohr HF, Schneider PM, Meyer zum, Rittner C. HLA-DRB1*1301 and *1302 protect against chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 1997. 26:503–507.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download