Abstract

We report a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) patient with male gynecomastia and testicular hydrocele after treatment with imatinib mesylate. A 42 yr-old male patient presented for management of hepatic masses. Two years earlier, he had undergone a small bowel resection to remove an intraabdominal mass later shown to be a GIST, followed by adjuvant radiation therapy. At presentation, CT scan revealed multiple hepatic masses, which were compatible with metastatic GIST, and he was prescribed imatinib 400 mg/day. During treatment, he experienced painful enlargement of the left breast and scrotal swelling. Three months after cessation of imatinib treatment, the tumors recurred, and, upon recommencing imatinib, he experienced painful enlargement of the right breast and scrotal swelling. He was diagnosed with male gynecomastia caused by decreased testosterone and non-communicative testicular hydrocele. He was given androgen support and a hydrocelectomy, which improved his gynecomastia. The mechanism by which imatinib induces gynecomastia and hydrocele is thought to be associated with an inhibition of c-KIT and platelet-derive growth factor. This is the first report, to our knowledge, describing concurrent male gynecomastia and testicular hydrocele after imatinib treatment of a patient with GIST.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are usually resistant to conventional chemotherapy. So, in case of unresectable or metastatic GIST, the prognosis was poor. However the prognosis of GIST has been changed dramatically after the introduction of imatinib mesylate (Glivec, previously called STI571). Imatinib inhibits not only bcr-abl tyrosine kinase and platelet-derive growth factor (PDGF), but also c-KIT kinase which is constitutively activated in GISTs. By this reason, imatinib becomes to be wide use for the treatment of GIST as well as chronic myeloid leukemia. Imatinib is relatively safe drug comparing with conventional cytotoxic drugs. Its adverse events were reported from several clinical trials. Common adverse events were usually mild and included nausea, edema, cramps, diarrhea, vomiting, rash, headache, fatigue, and arthralgia (1-5). In addition, severe or rare adverse events of imatinib have been reported, including severe skin rash, hair repigmentation, splenic rupture, bone marrow necrosis, and male gynecomastia. We report here a case of male gynecomastia coincident with testicular hydrocele in a patient treated with imatinib for metastatic GIST. Gynecomastia and testicular hydrocele are thought to be induced by imatinib through inhibition of c-KIT and PDGF. We will discuss the possible mechanisms of gynecomastia and testicular hydrocele.

A 42-yr-old man visited our hospital for management of liver masses. Two years earlier, he had undergone small bowel resection for removal of a 20 cm-sized mass, later shown to be a GIST. Following resection, he received postoperative adjuvant radiation therapy, at a total dose of 5,040 cGy. Upon presentation, multiple hepatic masses were revealed by computed tomography (CT). A paraffin block specimen of the previously resected small bowel mass was then reviewed. This tumor consisted of polygonal to spindle cells with moderate cellularity. The tumor cells showed pleomorphism, and necrosis was present. The mitotic figures were not frequent (2/50 high power fields). The tumor cells were immunohistochemically positive for c-Kit and focally positive for SMA, but negative for CD34 and S100, supporting the original diagnosis of GIST of interstitial cells of Cajal origin.

He was prescribed oral imatinib mesylate 400 mg daily. Just after starting drug treatment, the patient complained of periorbital swelling, but no dose reduction was required. Three months later, the hepatic lesions improved, showing a partial response, and nine months after his first visit to our hospital, CT scan and positron-emission tomography showed no evidence of disease. Treatment was discontinued after a further 5 months of imatinib mesylate, but a CT scan performed 3 months after finishing imatinib showed disease progression. A second period of imatinib treatment was started, at the same dose of 400 mg/day. One month later, the patient complained of breast pain and scrotal swelling. Physical examination revealed right gynecomastia and right painless scrotal swelling. A precise medical history was taken, at which point it was learned that left painful gynecomastia and scrotal swelling had developed during the first period of imatinib treatment, but that both had improved after stopping imatinib.

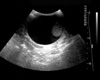

Pain in the right breast began on the 20th day of the second period of imatinib treatment. Decreased libido and impotence were noted. A testicular ultrasonogram showed a large amount of fluid in the right scrotal sac and his right testis was displaced downward (Fig. 1). The left scrotum and testis and the bilateral spermatic cords were normal. The patient was diagnosed with non-communicated testicular hydrocele.

The hormonal status of the patient was evaluated. Thyroid function test was within normal ranges. His serum thyroid stimulating hormone level was 1.1 µU/mL, his free T4 concentration was 1.3 ng/dL, his serum luteinising hormone level was 6.8 IU/L, and his follicle-stimulating hormone level was 14.1 IU/L. His serum testosterone concentration had decreased to 2.3 ng/mL. Androgen support was started and hydrocelectomy was performed. Pathologic examination of the hydrocele specimen showed it to be fibroadipose tissue without lining mesothelium. His gynecomastia improved after androgen support.

The most common adverse events of imatinib mesylate include edema, diarrhea, myelosupression, muscle cramps, skin rash, and conjunctival inflammation, most of which are mild (3, 6). In addition, rare or severe adverse events were reported. There have been case reports of severe skin rash, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and an acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis in patients treated with imatinib (7, 8), and 9 patients (5 men and 4 women) with gray hair before treatment had progressive repigmentation during imatinib treatment (9). In contrast to the repigmentation, imatinib mesylate-induced hypopigmentation was also reported (10-12). Among the more than 10,000 chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients treated with imatinib, there have been 3 reported cases of splenic rupture (13), and bone marrow necrosis (14), possibly due to increased apoptosis and the release of prothrombotic cellular material, has been reported. Imatinib was originally developed for inhibition of bcr-abl tyrosine kinase. However it is known that imatinib can also inhibit c-KIT tyrosine kinase and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) tyrosine kinase. The inhibition of c-KIT or PDGF is thought to be responsive for some of these adverse events.

A recent report has described seven cases of gynaecomastia (one grade 1 and six grade 2) in 38 CML patients treated with imatinib (15). PDGF signaling is important in testes organogenesis and Leydig cell differentiation (16). Also, PDGF-A is obligatory for adult Leydig cell recruitment and spermatogenesis (17). c-Kit activity is modulated by stem cell factor which in combination with insulin-like growth factor had effect on leuteinizing hormone receptor and increased the expression of StAR, CYP11A, CYP17, and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase mRNA expression (18). Therefore, imatinib can reduce testosterone biosynthesis by inhibiting c-KIT and PDGFR in the testis, and male gynecomastia can result from decreased testosterone (19, 20). In previous report, rise of progesterone and 17-hydroxyprogesterone could represent the accumulation of testosterone precursors as a consequence of impairment of key enzymes in the steroidogenic cascade (15). In our report, decreased testosterone was detected during gynecomastia, and testosterone supply improved gynecomastia and libido.

In our patient, the relationship between imatinib therapy and testicular hydrocele is evident by the fact that testicular hydrocele was repeatedly developed during imatinib therapy and improved after ceasing imatinib. The mechanism by which imatinib induces testicular hydrocele, however, is not clear, although it may arise through same mechanism of edema or fluid retention. Edema is the one of the most frequently reported adverse events, most of which are well tolerated. Unusual or severe cases of edema after imatinib such as cerebral edema, pleural effusion and severe periorbital edema were also reported (21-23). The mechanism of edema induced by imatinib is thought to be related with PDGFR. Signaling through PDGF-β receptors increases interstitial fluid pressure in the dermis (24, 25). On the contrary, inhibition of PDGF reduces interstitial hypertension and increases transcapillary transport in colonic carcinoma model (26). These studies suggested that the inhibition of PDGFR by imatinib is the possible mechanism of localized edema. Further investigation of the ability of imatinib to induce testicular hydrocele is warranted. To our knowledge, this is the first report of male gynecomastia and concurrent testicular hydrocele following imatinib treatment of a patient with GIST.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, Kantarjian H, Resta DJ, Reese SF, Ford JM, Capdeville R, Talpaz M. Activity of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in the blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Philadelphia chromosome. N Engl J Med. 2001. 344:1038–1042.

2. Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford JM, Lydon NB, Kantarjian H, Capdeville R, Ohno-Jones S, Sawyers CL. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001. 344:1031–1037.

3. Kantarjian H, Sawyers C, Hochhaus A, Guilhot F, Schiffer C, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Niederwieser D, Resta D, Capdeville R, Zoellner U, Talpaz M, Druker B, Goldman J, O'Brien SG, Russell N, Fischer T, Ottmann O, Cony-Makhoul P, Facon T, Stone R, Miller C, Tallman M, Brown R, Schuster M, Loughran T, Gratwohl A, Mandelli F, Saglio G, Lazzarino M, Russo D, Baccarani M, Morra E. Hematologic and cytogenetic responses to imatinib mesylate in chronic myelogenous leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2002. 346:645–652.

4. Sawyers CL, Hochhaus A, Feldman E, Goldman JM, Miller CB, Ottmann OG, Schiffer CA, Talpaz M, Guilhot F, Deininger MW, Fischer T, O'Brien SG, Stone RM, Gambacorti-Passerini CB, Russell NH, Reiffers JJ, Shea TC, Chapuis B, Coutre S, Tura S, Morra E, Larson RA, Saven A, Peschel C, Gratwohl A, Mandelli F, Ben-Am M, Gathmann I, Capdeville R, Paquette RL, Druker BJ. Imatinib induces hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in myeloid blast crisis: results of a phase II study. Blood. 2002. 99:3530–3539.

5. Talpaz M, Silver RT, Druker BJ, Goldman JM, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Guilhot F, Schiffer CA, Fischer T, Deininger MW, Lennard AL, Hochhaus A, Ottmann OG, Gratwohl A, Baccarani M, Stone R, Tura S, Mahon FX, Fernandes-Reese S, Gathmann I, Capdeville R, Kantarjian HM, Sawyers CL. Imatinib induces durable hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with accelerated phase chronic myeloid leukemia: results of a phase 2 study. Blood. 2002. 99:1928–1937.

6. Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, Van den Abbeele AD, Eisenberg B, Roberts PJ, Heinrich MC, Tuveson DA, Singer S, Janicek M, Fletcher JA, Silverman SG, Silberman SL, Capdeville R, Kiese B, Peng B, Dimitrijevic S, Druker BJ, Corless C, Fletcher CD, Joensuu H. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002. 347:472–480.

7. Hsiao LT, Chung HM, Lin JT, Chiou TJ, Liu JH, Fan FS, Wang WS, Yen CC, Chen PM. Stevens-Johnson syndrome after treatment with STI571: a case report. Br J Haematol. 2002. 117:620–622.

9. Etienne G, Cony-Makhoul P, Mahon FX. Imatinib mesylate and gray hair. N Engl J Med. 2002. 347:446.

10. Raanani P, Goldman JM, Ben-Bassat I. Challenges in oncology. Case 3. Depigmentation in a chronic myeloid leukemia patient treated with STI-571. J Clin Oncol. 2002. 20:869–870.

11. Tsao AS, Kantarjian H, Cortes J, O'Brien S, Talpaz M. Imatinib mesylate causes hypopigmentation in the skin. Cancer. 2003. 98:2483–2487.

12. Hasan S, Dinh K, Lombardo F, Dawkins F, Kark J. Hypopigmentation in an African patient treated with imatinib mesylate: a case report. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003. 95:722–724.

13. Elliott MA, Mesa RA, Tefferi A. Adverse events after imatinib mesylate therapy. N Engl J Med. 2002. 346:712–713.

14. Burton C, Azzi A, Kerridge I. Adverse events after imatinib mesylate therapy. N Engl J Med. 2002. 346:712–713.

15. Gambacorti-Passerini C, Tornaghi L, Cavagnini F, Rossi P, Pecori-Giraldi F, Mariani L, Cambiaghi N, Pogliani E, Corneo G, Gnessi L. Gynaecomastia in men with chronic myeloid leukaemia after imatinib. Lancet. 2003. 361:1954–1956.

16. Brennan J, Tilmann C, Capel B. Pdgfr-alpha mediates testis cord organization and fetal Leydig cell development in the XY gonad. Genes Dev. 2003. 17:800–810.

17. Gnessi L, Basciani S, Mariani S, Arizzi M, Spera G, Wang C, Bondjers C, Karlsson L, Betsholtz C. Leydig cell loss and spermatogenic arrest in platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-A-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2000. 149:1019–1026.

18. Huang CT, Weitsman SR, Dykes BN, Magoffin DA. Stem cell factor and insulin-like growth factor-I stimulate luteinizing hormone-independent differentiation of rat ovarian theca cells. Biol Reprod. 2001. 64:451–456.

19. Sette C, Dolci S, Geremia R, Rossi P. The role of stem cell factor and of alternative c-kit gene products in the establishment, maintenance and function of germ cells. Int J Dev Biol. 2000. 44:599–608.

20. Basciani S, Mariani S, Arizzi M, Ulisse S, Rucci N, Jannini EA, Della Rocca C, Manicone A, Carani C, Spera G, Gnessi L. Expression of platelet-derived growth factor-A (PDGF-A), PDGF-B, and PDGF receptor-alpha and -beta during human testicular development and disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002. 87:2310–2319.

21. Ebnoether M, Stentoft J, Ford J, Buhl L, Gratwohl A. Cerebral oedema as a possible complication of treatment with imatinib. Lancet. 2002. 359:1751–1752.

22. Goldsby R, Pulsipher M, Adams R, Coffin C, Albritton K, Wagner L. Unexpected pleural effusions in 3 pediatric patients treated with STI-571. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002. 24:694–695.

23. Esmaeli B, Prieto VG, Butler CE, Kim SK, Ahmadi MA, Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M. Severe periorbital edema secondary to STI571 (Gleevec). Cancer. 2002. 95:881–887.

24. Rodt SA, Ahlen K, Berg A, Rubin K, Reed RK. A novel physiological function for platelet-derived growth factor-BB in rat dermis. J Physiol. 1996. 495:193–200.

25. Heuchel R, Berg A, Tallquist M, Ahlen K, Reed RK, Rubin K, Claesson-Welsh L, Heldin CH, Soriano P. Platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor regulates interstitial fluid homeostasis through phosphatidylinositol-3' kinase signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999. 96:11410–11415.

26. Pietras K, Ostman A, Sjoquist M, Buchdunger E, Reed RK, Heldin CH, Rubin K. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor receptors reduces interstitial hypertension and increases transcapillary transport in tumors. Cancer Res. 2001. 61:2929–2934.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download