Abstract

Choroid plexus cysts (CPCs) are the most commom neuroepithelial cysts, occuring in more than 50% of some autopsy series. They are typically small and asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally in older patients, usually in the trigone of the lateral ventricle. Symptomatic CPCs (usually exceptionally large, 2-8 cm) are rare. The authors report a case of large symptomatic choroid plexus cyst, located in the trigone of the right lateral ventricle in a 26-yr-old man who presented with headache and vomiting. The patient underwent endoscopic removal through a burr hole placed 3 cm from the midline and just behind the hair line. The histological examination of the cyst wall was consistent with choroid epithelium. Despite of postoperative intraventricular hemorrhage and catheter infection, he discharged home without neurologic deficits. The endoscopic fenestration rather than excision should be considered as the first surgical procedure because the goal of treatment is shrinkage of the cyst until normal cerebrospinal fluid flow is restored.

Different cystic lesions may occur both in the brain parenchyma and in the ventricular system, alone or in association to hydrocephalus. These include porencephalic cysts, ependymal cysts, cysts arising from a defect in the hemispheric cleavage and from the choroid plexus (1).

Choroid plexus cysts (CPCs) are the most commom neuroepithelial cysts. They are typically small and asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally in older patients, usually in the trigone (also known as atrium) of the lateral ventricle. Symptomatic CPCs (usually exceptionally large, 2-8 cm) are rare (2).

Symptomatic CPCs were treated to date either by direct surgical fenestration or excision through a craniotomy or by a cyst-peritoneal shunt. The development of endoscopic techniques has provided a new modality of surgical treatment of these cysts, which allows one to avoid further treatment in most cases (3).

We report on a case of a large symptomatic CPC, located in the trigone of the right lateral ventricle resulting in an blockage of the right foramen of Monro in a 26-yr-old man who underwent endoscopic removal. A brief review of the literature is included.

A 26-yr-old man, with no other medical history, complained of progressive headache and vomiting for 3 months. A neurological and physical examination revealed no abnormal findings. Laboratory findings including karyotyping were normal.

Computed tomographic (CT) scans demonstrated only asymmetry of the lateral ventricles, with enlargement of the right lateral ventricle (Fig. 1). Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large, cystic, nonenhancing lesion with a thin wall in the right lateral ventricle. The cyst contents had the same signal intensity as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on MRI (Fig. 2).

The patient underwent endoscopic transventricular cyst resection. The patient was positioned supine with head in neutral position and the thorax elevated 15 degree. A linear incision on the right frontal scalp, parallel to the sagittal suture, was applied to the pericranium. A 15-mm burr hole was placed 3 cm from the midline and just behind the hair line. The dura was incised in cruciate fashion. A 12-French introducer sheath was inserted into the frontal horn of the right lateral ventricle under freehand-guidance. A 2.7 mm rigid telescope was introduced, and the cyst wall obstructing the right foramen of Monro was identified (Fig. 3A). An avascular area in the midportion of the cyst wall above the foramen of Monro was chosen for fenestration. The cyst wall was punctured by gentle pushing the tip of the probe. With microscissors and forceps, the cyst wall was opened as widely as possible (Fig. 3B). CSF in the cyst was expelled and the foramen of Monro was opened. The shrunken cyst was separated from the ventricle around the foramen of Monro. We drew the margin of opening with forcep carefully. The cyst was removed totally with no resistance (Fig. 4). At that time, subsequent intraventricular hemorrhage was identified, so continuous irrigation of lactated Ringer's solution was done because the bleeding focus could not be found. After identifying no active bleeding, the neuroendoscope was then withdrawn remaining the external ventricular drainage catheter. A small piece of Gelfoam was placed in the cortical chimney, and the wound was closed in a routine fashion.

Histological examination revealed a fibrous vascular stroma covered by cuboidal epithelium. The appearance was that of choroid plexus neuroepithelial cells (Fig. 5).

Immediately after surgery, he complained headache with no neurologic deficit. Intraventricular hemorrhage was detected on CT scan obtained at that time. External ventricular drainage catheter was changed due to catheter infection at 8 days after surgery and it was removed at 14 days after surgery. A CT scan performed 14 days after endoscopic removal of the cyst showing no intraventricular hemorrhage (Fig. 6). Infection was controlled soon. He was discharged home at 37 days after the first surgery with no neurologic deficit. His headache significantly improved on follow-up visits.

Netsky and Shuangshoti have reported cysts of the choroid plexus in 38% of the telencephalic choroid plexuses in their 124 autopsy cases (4). Small CPCs are usually asymptomatic and are usually incidentally encountered at autopsy (5). Their size usually does not extend beyond 1.5-2 cm in diameter at the most (4, 5). Exceptionally, however, they may be large enough to cause symptoms. They are most frequently found in children with a preponderance for the male sex and account for approximately 3% of all pediatric cerebral pathological entities (6). These cysts may occur in any ventricular cavity. They can be uni- or bilateral, single or multiple. In the lateral ventricle, they usually congregate at and around the trigone (6).

The presence of CPC on prenatal screening has been associated with trisomy 18 and possibly trisomy 21, but the majority of cysts are asymptomatic incidental findings. The majority of these cysts spontaneously resolve by birth or early infancy. Very few reports exist of CPCs persisting into adulthood (7).

When present, symptoms are secondary to the obstruction of CSF, particularly at the foramen of Monro. Patients frequently present with intermittent worsening of their symptoms, which implies a mobile cyst with a ball-and-chain configuration. Imaging of symptomatic patients usually reveals dilated ventricle. Patients with unilateral lesions above the third ventricle can present with asymmetrical dilatation of the lateral ventricle. Other possible clinical manifestations of large cysts may range from increased pressure to epilepsy (7).

Histologically, CPCs are consist of a fibrous outer membrane and an inner layer of cuboidal choroid plexus epithelium, often with ciliated cells (6, 8). These lesions have been related to the histogenesis of the choroid plexus. Most authors believe the origin of these lesions is the primitive neuroepithelium that lines the neural tube. The most unifying theory about their pathogenesis suggests that a neuroepithelial tube or a small cyst is formed by a folding of the neuroepithelium into the choroid's matrix and of stroma into the ventricle (evagination and invagination). It occurs as finger-like projections to create choroidal villi. The neck of the folded epithelial sacs occasionally may be pinched off and become separated from the ventricle. The accumulation of secretions from the secretory activity of these epithelial cells in the congenitally formed cyst and the fluid activity transported from the exterior will produce a clear CSF-like substance (1).

Computerized tomography most often reveals a focal enlargement of the trigone with a well-defined low density mass in the lateral ventricle of similar density to CSF. The cyst does not enhance after administration of contrast material, whereas the enhancing choroid plexus is usually displaced. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates the precise location of the cyst in the lateral ventricle. The cyst wall can be easily identified, even though it is very thin and closely applied to the ventricular lining. The content of the cyst has a signal on both T1- and T2-weighted MR images, corresponding to CSF (2).

The differential diagnosis of intraventricular cysts includes colloid cysts, ependymal cysts, arachnoid cysts, Rathke cyst, cysticercosis, and histocytosis X. Immunohistochemical studies are useful in differentiating between these different types of cysts. The epithelium of choroid and ependymal cysts shows immunoreactivity for markers of normal neuroepithelial structures of the CNS. Choroid plexus epithelium has a positive result with transhyretin, and ependymal epithelium has a positive result with glial fibrillary acidic protein. On the contrary, the epithelial walls of colloid cysts and Rathke cleft cysts express epithelial markers, such as mucin (mucicarmin). These markers support the theory of a neuroepithelial origin of a CPC or ependymal cyst and an ectodermal origin of a colloid cyst or Rathke cleft cyst (9).

Regarding treatment, it should be emphasized that the majority of these cysts are asymptomatic and only require periodic observation. Spontaneous regression of CPCs has also been described. There are several surgical options for treating symptomatic CPCs: 1) creation of communication of the cyst cavity with the ventricle, either by open surgery or through ventriculoscopy; 2) placement of ventriculocystoperitoneal shunt; 3) stereotactic evacuation of the cyst content; and 4) direct surgical approach with total or partial resection of the lesion (6).

CPCs represent an ideal indication to the endoscopic surgery. In fact, the endoscopic approach to the cyst is a scarcely invasive technique, which allows us to avoid the direct approach by craniotomy or the insertion of a shunt in most cases. However, the surgical approaches and the technique of endoscopic treatment are rather variable, according to the location of the cyst, and are today debated (3).

CPCs develop near the foramen of Monro, thus producing monoventricular hydrocephalus (10). The endoscopic approach to the CPCs should be different, according to the size and the residual lateral ventricle. The burr hole must be performed at the level of the more superficial point of the cyst and according to an easy and direct trajectory, as defined by MRI sequence. Large and multiple fenestrations are necessary to avoid closure of the stomy and recurrence of the cyst (3). In our case, burr hole was placed 3 cm ipsilateral from the midline and 5 cm anterior to the coronal suture. However, Gangemi et al. advised to approach large choroid plexus cysts through a contralateral occipital burr hole and to perform the fenestration from the contralateral not enlarged ventricle to the cyst, because when the cyst is large and occupies almost completely the enlarged lateral ventricle, the cannulation of the ipsilateral ventricle is difficult or even impossible (3).

Total resection of these lesions was recommended when the cyst can be easily separated from the ependymal walls like our case. When the cyst is firmly adherent to surrounding brain close to the choroid plexus, it is better to leave a strip of the cyst wall undisrupted rather than risk of injury to important fine vessels (6). There must be a caution in dissecting cyst from the ventricular wall because of such a narrow surgical field like endoscopic approach.

Symptomatic large CPC is very rare. The endoscopic surgery plays a very important role in the treatment of symptomatic CPC and may replace the microsurgical approach and shunting in most cases. The endoscopic fenestration rather than excision should be considered as the first surgical procedure because the goal of treatment is shrinkage of the cyst until normal CSF flow is restored.

Figures and Tables

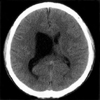

Fig. 1

Preoperative computed tomographic scan demonstrating only asymmetry of the lateral ventricles, with enlargement of the right lateral ventricle.

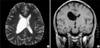

Fig. 2

Preoperative MR images demonstrate a large cystic lesion occupying almost completely the enlarged right lateral ventricle with CSF-like signal intensity and a unilateral right-sided hydrocephalus with deviation of the septum pellucidum to the left. (A) T2-weighted axial image. (B) T1-weighted coronal image.

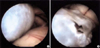

Fig. 3

(A) Intraoperative image reveals whitish wall of cyst obstructing the right foramen of Monro completely. (B) After the midportion of the cyst wall above the foramen of Monro was fenestrated, cystic fluid was expelled.

References

1. Odake G, Tenjin H, Murakami N. Cyst of the choroid plexus in the lateral ventricle: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1990. 27:470–476.

2. Pelletier J, Milandre L, Peragut JC, Cronqvist S. Intraventricular choroid plexus "arachnoid cyst". MRI findings. Neuroradiology. 1990. 32:523–525.

3. Gangemi M, Maiuri F, Godano U, Mascari C, Longatti PL, Marzucco M. Endoscopic treatment of para- and intraventricular cerebrospinal fluid cysts. Minim Invas Neurosurg. 2000. 43:153–158.

4. Netsky MG, Shuangshoti S. The choroid plexus in health and disease. 1975. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press;351.

5. Choi JH, Kim SH, Koh HS, Youm JY, Song SH, Kim Y. A symptomatic choroid plexus cyst in the lateral ventricle: case report. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 1998. 27:1283–1287.

6. Hanbali F, Fuller GN, Leeds NE, Sawaya R. Choroid plexus cyst and chordoid glioma: report of two cases. Neurosurg Focus. 2001. 10:1–6.

7. Heilman CB, Zerris VA. Transient choroid plexus cysts and benign asymmetrical ventricles: a case suggesting a possible link: case report. Neurosurgery. 2003. 52:213–215.

8. Martinez-Lage JF, Poza M, Sola J, Puche A. Congenital arachnoid cyst of the lateral ventricles in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 1992. 8:203–206.

9. Radaideh MM, Leeds NE, Kumar AJ, Bruner JM, Sawaya R. Unusual small choroid plexus cyst obstructing the foramen of Monroe: case report. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002. 23:841–843.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download