Abstract

The Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale (IIRS) measures illness-induced disruptions to 13 domains of lifestyles, activities, and interests. A stable three-factor structure has been well documented; however, the cross-cultural validity of this scale needs to be tested. This study investigated the factor structure of the Korean version of IIRS in 712 outpatients at a university medical center. A predominant diagnosis of the patients was rheumatoid arthritis (47%). The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), and Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) were also administered. Exploratory Principal Component Analysis identified a two-factor structure, "Relationships and Personal Development (RPD)" and "Instrumental", accounting for 57% of the variance. Confirmatory analyses extracted an identical factor structure. However, a goodness-of-the fit test failed to support two-factor solution (χ2=138.2, df=43, p<.001). Two factors had high internal consistency (RPD, α=.89; Instrumental, α=.75) and significantly correlated with scores of HAQ (RPD, r=.53, p<.001; Instrumental, .r=44, p<.001) and CES-D (RPD, .r=55, p<.001; Instrumental, .r=43, p<.001). These findings supported construct validity of the Korean version of IIRS, but did not support cross-cultural equivalence of the factor structure.

Individuals with chronic disease suffer from life style disruption and difficulty with every day activities or interests (1-3). This is largely due to a devastating illness itself (e.g., pain, physical disability) but in part also due to treatment-related factors such as adverse effects (3). Devins and his colleagues termed this illness-induced lifestyle disruption as "illness intrusiveness" (4). It was suggested illness intrusiveness stands as a common underlying determinant of quality of life in chronic disease or a mediator of psychosocial impact of illness (3, 5).

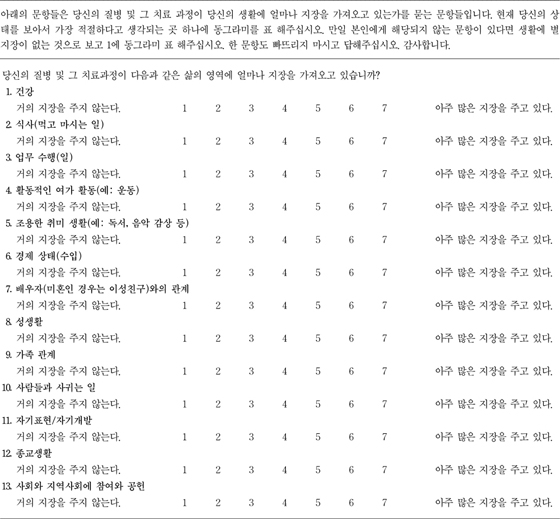

They also developed a thirteen-itemed self-report scale called the Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale (IIRS), which defines illness intrusiveness as lifestyle and activity disruptions that arise as a result of an illness and/or its treatment (4). Specifically, IIRS measures illness-induced interference in 13 life domains important to quality of life; health, diet, work, active recreation (sports), passive recreation (reading, listening to music), finances, relationship with partner, sex life, family relations, other social relations, self-expression/self-improvement, religious expression, and community and civic involvement (4). This scale has been widely used in a various population of chronic diseases including end-stage renal disease (4, 6), multiple sclerosis (5), rheumatoid arthritis (2), cancer (7), hyperhidrosis (8), lupus (9), and transplant population (10) and more recently in psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorder (11), bipolar disorder (12), and sleep disorder (13).

Moderate to high reliability and validity of IIRS was reported through a number of studies (e.g., see review by Devins [3]). IIRS also showed a stable and common three factor solution across diverse patient populations further enabling its comparison among different disease groups (14).

Despite the rigorous attention in psychosomatic research and the degree of examination of the psychometric properties this scale has received, one area needing further evaluation is the cross-cultural adaptation of IIRS (14). Even the psychological instrument with excellent psychometric properties in the original language sometimes yields the poor construct validity in different language versions (15). To our best knowledge, French and Chinese language versions are currently being investigated but have not yet been published and a Korean version had been developed but its validity has never been tested (16).

In order to examine this issue, we developed a Korean version of IIRS and tested its cross-cultural adaptation through investigating construct validity (i.e., factor analysis, internal consistency, and correlation with other scores of functional disability and depressive symptoms).

Subjects were 712 outpatients diagnosed with a variety of medical diagnoses. Diagnostic distribution included sero-positive rheumatoid arthritis (46.5%); end-stage renal disease under current dialysis (14.5%), either peritoneal or hemodialysis; diabetes (13.1%); hypertension (11.7%); cancer (9.4%) and others (4.9%). The sample was predominantly women (65.6%), married (77.9%) and completed high school or higher education (62.5%). Mean age was 49.6 yr (SD=14.75) and mean duration of illness was 8.3 yr (SD=5.2).

All the patients were recruited from the outpatient units of the Department of Internal Medicine and Hospital for Rheumatic disease at Hanyang University Medical Center in Seoul during one month period. Research associates approached candidate patients after reviewing the medical charts for the above mentioned five diseases and obtained informed consent to participate in the survey. By convenient sampling, 827 patients were approached and 115 either refused to participate or did not complete the questionnaire, leaving 712 as a final sample. The study was approved by the ethics review board at the Hanyang University Medical Center.

Subjects were asked to complete the Korean version of the IIRS (IIRS-K), Korean Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and the Korean version of The Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale (CES-D). Cross-cultural validation data are available for HAQ (17) and CES-D (18). Additionally, clinical and socio-demographic information was obtained from the patients and their medical records.

The IIRS captures 13 domains of everyday functioning and asks the respondents how illness or its treatment interferes with each domain. Respondents rate along a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1=not very much to 7=very much [4]. A total score can range from 13 to 91. Authors of this study agreed on a Korean language version (IIRS-K) after a translation and back-translation process.

Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) (19), widely used self-rating instrument to measure functional disability in chronic illnesses and the Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale (CES-D), a self-reporting depression scale composed of 20 items were also administered (20). Previous literature supports the association of IIRS total score with disability and depressive symptoms (2, 9, 21).

Initial factor structure of IIRS-K was examined by exploratory principle component analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation in randomly split cases (n=356). This exploratory method was chosen because our objective of this study was to validate the Korean version of IIRS, although a three factor solution and its stability among diagnostic groups is known for original English version (4).

To further corroborate the stability of factor structure, remaining cases (n=356) were analyzed by confirmatory PCA with oblique rotation. Maximum likeliness factor analysis was also employed to test the goodness-of-fit of the model. We conducted Pearson correlation among total or factor scores of IIRS, HAQ and CES-D scores. Finally, we calculated the internal consistency of the items and factors. All data analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 10.0 for Windows.

Exploratory PCA with Varimax rotation in the exploratory sample (n=356) extracted two factors, of which the number was determined by size of eigenvalue, variance explained, and the scree test. Items with factor loading exceeding 0.40 and no cross-loadings were assigned to factors.

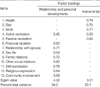

As shown in Table 1, Factor 1 labeled "Relationships and Personal Development" included eight items: financial situation, relationship with spouse, sex life, family relations, other social relations, self-expression/self improvement, religious expression, community and civic involvement. Factor 2, termed "Instrumental" included four items: health, diet, work, and passive recreation. This two-factor solution accounted for 57% of the total variance. Item 4, active recreation had cross loadings (0.40 or greater on two-factors) and was excluded for subsequent statistical analyses.

As the two factors in exploratory analysis were intercorrelated (0.70), a confirmatory PCA with oblique rotation was used for the remaining half of the cases (n=356). The same two-factor structure was extracted. This result was replicated for total subjects (n=712). However, when we employ maximum likelihood factor analysis with oblique rotation to test the goodness-of-fit of the two factor model, statistically significant chi-square test resulted suggesting more factors are needed (χ2=138.2, df=43, p<0.001).

We calculated reliability (alpha coefficient) of two subscales in the entire sample (n=712). The alpha coefficients for Relationships and Personal Development subscale were 0.89 and Instrumental 0.75. Each item of IIRS-K had coefficients ranging 0.48-0.74; total items 0.92. Thus, reliability was high for both factors and also for total items.

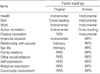

This study examined the factor structure of IIRS-K in a sample of chronic medical diseases, predominantly rheumatoid arthritis. Exploratory PCA and further confirmatory factor analysis extracted two factor structure, "Relationships and Personal Development" and "Instrumental". This result is comparable to original IIRS with three-factor solution; instrumental, intimacy, and relationships and personal development (14).

Overall speaking, more relational aspects were emphasized in the factor structure of IIRS-K when compared with the original IIRS (Table 2). For example, Intimacy (Item 7.8) in the original IIRS submerged in Relationships and Personal Development (Item 6-13) in IIRS-K. These two items (relationship with spouse and sex life) may be seen as a part of private and intimate sector distinct from relationship with others by North Americans, but Koreans may see that relationship and involvement with partners as a continuum of relations with others. This value of interdependence and harmony with others rather than individualism was described for Asians (22) and sometimes explained in the Confucian ideal (23).

Even Item 6, financial situation was loaded under factor "Relationships and Personal Development", not "Instrumental". It is not uncommon in Korea many patients with chronic illnesses depend financially on their family or relatives for medical expenditure because of incomplete coverage by medical insurance and welfare system. One research shows that Asian Americans are more likely to seek social support for their stress compared with European Americans (24).

Items on Instrumental (item 1, 2, 3, 5) of IIRS-K bear some differences to original Instrumental (item 1, 3, 4, 6). Item 2, diet had cross-loading and was excluded in IIRS but included in this study. Besides, Item 4, active recreation included as Instrumental in IIRS was dropped in IIRS-K. This item had cross loading on both Instrumental and Relationships and Personal Development. Koreans seem to foster more interpersonal aspects of exercises, which was shown as an example in the questionnaire. Item 5, passive recreation belonged to Instrumental, which was under Relationships and Personal Development in original IIRS. Once again, examples for passive recreation were reading and listening to music, which may be seen as mechanical and daily activities.

Therefore, we suggest that difference of factor structure from the original IIRS is in fact, reflection of cultural emphasis on relation with others and difference in life styles.

The limitation of corroborating two-factor solution in IIRS-K is that confirmatory maximum likelihood method failed to support the goodness-of-fit of the model. It generally means more factors are needed to account the structure but also may reflect sensitivity to sample size. Moreover, two factors had moderate to high internal consistency and correlated with disease characteristics (i.e., functional disability) and emotional distress (i.e., depression) well demonstrating the construct validity of two factors.

Other weakness of this study includes convenient sampling method and disproportion of diagnostic distribution may hazard the representativeness of the subjects. Taken together, these findings suggest construct validity of IIRS-K; however, corroborating two-factor solution needs further investigation. Likewise, we did not find cross-cultural equivalence of three-factor structure of IIRS.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thank Mr. Adam Turner, the Director of English Writing Center, Hanyang University and the staff at the Department of Internal Medicine and the Hospital for Rheumatic Disease, Hanyang University Medical Center.

References

1. Devins GM, Seland TP. Emotional impact of multiple sclerosis: recent findings and suggestions for future research. Psychol Bull. 1987. 101:363–375.

2. Devins GM, Edworthy SM, Guthrie NG, Martin L. Illness intrusiveness in rheumatoid arthritis: Differential impact on depressive symptoms over the adult life span. J Rheumatol. 1992. 19:709–715.

3. Devins GM. Illness intrusiveness and the psychosocial impact of lifestyle disruptions in chronic life-threatening disease. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1994. 1:251–263.

4. Devins GM, Binik YM, Hutchinson TA, Hollomby DJ, Barre PE, Guttmann RD. The emotional impact of end-stage renal disease: importance of patients' perception of intrusiveness and control. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1983. 13:327–343.

5. Devins GM, Styra R, O'Conor P, Gray T, Seland TP, Klein GM, Shapiro CM. Relationship and Personal Developments impact of illness intrusiveness moderated by age in multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health Med. 1996. 1:179–191.

6. Devins GM, Mandin H, Hons RB, Burgess ED, Klassen J, Taub K, Schorr S, Letourneau PK, Buckle S. Illness intrusiveness and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: comparison and stability across treatment modalities. Health Psychol. 1990. 9:117–142.

7. Devins GM, Stam HJ, Koopmans JP. Psychosocial impact of laryngectomy mediated by perceived stigma and illness intrusiveness. Can J Psychiatry. 1994. 39:608–616.

8. Cinà CS, Clase CM. The illness intrusiveness rating scale: a measure of severity in individuals with hyperhidrosis. Qual Life Res. 1999. 8:693–698.

9. Devins GM, Edworthy SM. Illness intrusiveness explains race-related quality-of-life differences among women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2000. 9:534–541.

10. Schimmer AD, Elliott ME, Abbey SE, Raiz L, Keating A, Beanlands HJ, McCay E, Messner HA, Lipton JH, Devins GM. Illness intrusiveness among survivors of autologous blood and marrow transplantation. Cancer. 2001. 92:3147–3154.

11. Antony MM, Roth D, Swinson RP, Huta V, Devins GM. Illness intrusiveness in individuals with panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or social phobia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998. 186:311–315.

12. Robb JC, Cooke RG, Devins GM, Young LT, Joffe RT. Quality of life and lifestyle disruption in euthymic bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 1997. 31:509–517.

13. Devins GM, Edworthy SM, Paul LC, Mandin H, Seland TP, Klein G, Costello CG, Shapiro CM. Restless sleep, illness intrusiveness, and depressive symptoms in three chronic illness conditions: rheumatoid arthritis, end-stage renal disease, and multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 1993. 37:163–170.

14. Devins GM, Dion R, Pelletier LG, Shapiro CM, Abbey S, Raiz LR, Binik YM, McGowan P, Kutner NG, Beanlands H, Edworthy SM. Structure of lifestyle disruptions in chronic disease: a confirmatory factor analysis of the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale. Med Care. 2001. 39:1097–1104.

15. Zheng YP, Wei LA, Goa LG, Zhang GC, Wong CG. Applicability of the chinese beck depression inventory. Compr Psychiatry. 1988. 29:484–489.

16. Suh M, Noh S, Devins GM, Kim K, Song J, Cho N, Hong Y, Kim I, Choi H, Jung S, Kim E. Readjustment and social support of the post hospitalized stroke patients. J Korean Acad Nurs. 1999. 29:639–655.

17. Bae SC, Cook EF, Kim SY. Psychometric evaluation of a Korean Health Assessment Questionnaire for clinical research. J Rheumatol. 1998. 25:1975–1979.

18. Cho MJ, Kim KH. Use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale in Korea. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998. 186:304–310.

19. Pincus T, Summey JA, Soraci SA Jr, Wallston KA, Hummon NP. Assessment of patient satisfaction in activities of daily living using a modified Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum. 1983. 26:1346–1353.

20. Radoff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measurement. 1977. 1:385–401.

21. Devins GM, Edworthy SM, Paul LC, Mandin H, Seland TP, Klein GM. Illness intrusiveness and depressive symptoms over the adult years: is there a differential impact across chronic conditions? Can J Behav Sci. 1993. 25:400–413.

22. Chang SC. The self: a nodal issue in culture and psyche-an Eastern perspective. Am J Psychother. 1982. 36:67–81.

23. Cheung P. Culture and behaviour of East Asians. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1991. 25:14–16.

24. Talyor SE, Sherman DK, Kim HS, Jarcho J, Takagi K, Dunagan MS. Culture and social support: who seeks it and why? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004. 87:354–362.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download