Abstract

Melioidosis is an infection of the Gram-negative bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei. While it is known as an important cause of sepsis or chronic abscess-forming disease in Southeast Asia and northern Australia, no case has yet been reported in Korea. A 50-yr-old man visited our hospital for intermittent fever associated with dry cough and sputum. Roentgenographic examination showed migrating pulmonary infiltration. Symptoms and chest radiograph and computed tomography (CT) image findings did not improve despite use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Gram-negative bacteria were isolated on bronchoscopic washing culture and were identified as B. pseudomallei on DNA sequencing of 16S ribosomal RNA with 100% homology. Treatment for melioidosis was commenced with high dose ceftazidime, and the patient's fever, cough, and sputum were improved and the lesion on chest radiograph and CT almost disappeared.

Melioidosis is predominantly a tropical disease and most cases are reported during the rainy season in endemic area. It is characterized by abscess-formation in the lung, liver, spleen, skeletal muscle and prostate with the lung being the most commonly involved organ. The clinical features are variable from rapidly progressing septicemia to chronic debilitating abscess-forming disease. Understanding about melioidosis is important in tuberculosis endemic areas, because its progression and roentgenographic findings are so similar to tuberculosis that it is not rare for melioidosis to be misdiagnosed as tuberculosis. We report a case of melioidosis presenting as intermittent fever and migrating pulmonary infiltration. The patient was a 50-yr-old man who was diagnosed with melioidosis on bronchoscopic washing culture and whose symptoms improved after treatment with high dose ceftazidime.

A 50-yr-old man visited our hospital because of intermittent fever associated with cough, sputum, generalized myalgia and general weakness for about four weeks. He had lived in Indonesia for twenty years for business, and visited a local hospital in Indonesia and was treated for typhoid fever without improvement of symptoms. He was previously healthy and had no history of diabetes. Initial chest radiograph and computed tomography (CT) images showed multiple satellite nodules in the left lower and upper lobes, and judging from that roentgenographic examination, tuberculosis was the most probable diagnosis (Fig. 1). Bronchoscopy showed no endobronchial lesion and washing cytology and culture were also negative. We prescribed moxifloxacin but his symptoms showed no improvement. Three months later we rechecked chest radiograph and CT findings, and found new infiltration in the left lower lobe and improvement of lesions in the left upper and lower lobes (Fig. 2). So he was admitted to our hospital for further evaluation. On physical examination initial body temperature was 38℃ and there was no other abnormal finding. Laboratory findings included white blood cell count of 5,240/µL and hemoglobin value of 11.6 g/dL. Hepatic function and renal function were normal. IgA was 227 mg/dL (normal range: 90-400 mg/dL) and anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies with cytoplasmic staining pattern (CANCA) was negative.

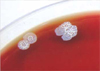

Bronchoscopy was done once more and no endobronchial lesion was found. However, secretion was seen in left lower lobe, so washing cytology and culture was done. Cytology was negative but a species of bacteria grew on blood agar media (Fig. 3). It was Gram-negative, non-spore forming and showed as a safety pin shaped organism on microscopic examination (Fig. 4). By biochemical examination of API20NE strip and VITEK GNI card (BioMerieux, Inc., Hazelwood, U.S.A.), the organism was identified as Burkholderia pseudomallei (1). On DNA sequencing of 16S ribosomal RNA, it was compatible with B. pseudomallei with 100% homology and formed a characteristic rugose colony on blood agar.

We prescribed ceftazidime 2 g intravenously every 8 hr and he did not complain of intermittent fever any more. The cough, sputum and general condition improved slowly. After one week of intravenous ceftazidime, he was discharged with oral amoxicillin-clavulanate (750 mg every 8 hr). One month later the cough and sputum were almost disappeared but his general weakness persisted although it was also improving.

Four months later we rechecked chest CT to show an improvement of infiltration in left lower lobe. He said his condition was as good as his previous state before suffering from melioidosis. One month later, we stopped administrating oral antibiotics to him, which resulted in him taking amoxicillin-clavulanate for total five months.

This is the first case report of melioidosis in Korea. The endemic area includes Southeast Asia, North Australia, Madagascar, and Guam (2). In northeast Thailand, melioidosis accounts for 20% of all community-acquired septicemias, and causes death in 40% of treated patients.

Melioidosis was first described by Whitmore in 1911 and more than 100 cases had been reported by 1917 (3). Since then, with sporadic cases being reported during and after World War II and many soldiers fighting in Vietnam suffering from this disease, Western countries began to take an interest in melioidosis.

B. pseudomallei is a motile aerobic, non-spore-forming and Gram-negative bacillus. The colonies develop a rugose appearance, and take up crystal violet dye from the medium. Gram stain shows Gram-negative rods with bipolar staining. It is resistant to many antibiotics. Although it is Gram-negative bacterium, it is usually resistant to aminoglycoside, 1st & 2nd cephalosporin, macrolide, rifamycin and colistin, but is susceptible to ampicillin/sulbactam, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, bactrim, 3rd cepha and carbapenem (4). B. pseudomallei is a soil saprophyte and can be recovered readily from water and wet soils in rice paddy fields. For example, in Thailand the organism can be cultured readily from more than 50% of rice paddies (5).

Melioidosis is acquired by inoculation or inhalation, but not by ingestion. Vertical transmission at childbirth and sexual transmission have also been reported (6). Melioidosis has a wide range of clinical manifestations. It presents as a febrile illness, ranging from an acute fulminant sepsis to a chronic debilitating localized infection. The disease is characterized by abscess formation. The lung is the most commonly affected organ, either presenting with cough and fever resulting from a primary lung abscess or pneumonia. Seeding and abscess formation can arise in any organ, and the liver, spleen, skeletal muscle and prostate are common sites.

Localized pulmonary melioidosis often cannot be differentiated from tuberculosis on clinical and chest radiography findings. However, melioidosis differs from tuberculosis in the following ways. First, some melioidosis cases have rapid clinical and roentgenographic progression within a few days. Second, melioidosis usually responds to treatment well and has apparent roentgenographic improvement within 1-2 weeks. Third, parapneumonic effusion develops in 5-15% of cases, but the amount is not large and associated pulmonary infiltration is always present. In contrast, tuberculosis pleurisy in which a large amount of pleural fluid is present without underlying pulmonary infiltration is common. Fourth, hilar adenopathy is very rare in melioidosis (7).

Diagnosis of melioidosis is made by isolation of B. pseudomallei from any site; for example blood, sputum, abscess fluid and throat swab. The organism is not carried asymptomatically (8). Abdominal ultrasound should be done in all suspected cases. Since splenic abscess is much less common in other diseases, its presence is more likely to suggest melioidosis. Serologic test is nonspecific but can be used to exclude this disease.

The antibiotic of choice is ceftazidime (40 mg/kg intravenous injection every 8 hr), while other 3rd generation cephalosporin is less effective (9). Intravenous antibiotic is usually given for more than 10 days until clinical improvement. After clinical improvement, patients can take oral antibiotics. Four-drug combination is usually recommended as oral antibiotics, and those are chloramphenicol (40 mg/kg per day in four divided doses), doxycycline (4 mg/kg per day in two divided doses), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (10 mg and 50 mg/kg per day, respectively, in two divided doses). But in case of children and women, amoxicillin-clavulanate is recommended. Oral treatment is usually continued for twenty weeks. In brief, high dose ceftazidime followed by long term oral antibiotics is considered to be most effective treatment. The abscess should be drained if it is accessible and large.

The distribution and frequency of melioidosis is probably greatly underestimated (10). In tuberculosis endemic areas, it is important to understand melioidosis and differentiate this disease from tuberculosis because the treatment of the two diseases is completely different.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Three months later, a new infiltration appears in the left lower lobe and lesions in the left upper and lower lobes improved.

References

1. Coenye T, Goris J, Spilker T, Vandamme P, LiPuma JJ. Characterization of unusual bacteria isolated from respiratory secretions of cystic fibrosis patients and description of Inquilinus limosus gen. nov., sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 2002. 40:2062–2069.

2. Currie BJ, Fisher DA, Howard DM, Burrow JN, Lo D, Selva-Nayagam S, Anstey NM, Huffam SE, Snelling PL, Marks PJ, Stephens DP, Lum GD, Jacups SP, Krause VL. Endemic melioidosis in tropical northern Australia; a 10 year prospective study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000. 31:981–986.

3. Krishnaswami CS. Morphia injectors septicemia. Indian med Gaz. 1917. 52:296–299.

4. Jenney AW, Lum G, Fisher DA, Currie BJ. Antibiotic susceptibility of Burkholderia pseudomallei from tropical northern Australia and implications for therapy of melioidosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001. 17:109–113.

5. Wuthiekanun V, Smith MD, Dance DA, White NJ. The isolation of Pseudomonas pseudomallei from soil in Northeastern Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995. 89:41–43.

6. Abbink FC, Orendi JM, de Beaufort AJ. Mother-to-child transmission of Burkholderia pseudomallei. N Engl J Med. 2001. 344:1171–1172.

7. Kiatboonsri Sumalee. Melioidosis. Lung Disease in the Tropics. 1990. 51:135–155.

9. White NJ, Dance DA, Chaowagul W, Wattanagoon Y, Wuthiekanun V, Pitakwatchara N. Halving of mortality of severe melioidosis by ceftazidime. Lancet. 1989. 2:697–701.

10. Angus BJ, Smith MD, Suputtamongkol Y, Mattie H, Walsh AL, Wuthiekanun V, Chaowagul W, White NJ. Pharmacokinetic-, pharmacodynamic evaluation of ceftazidime continuous infusion versus intermittent bolus injection in septicaemic melioidosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000. 50:184–191.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download