Abstract

We report a case of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in a 30-yr-old female housewife caused by Penicillium species found in her home environment. The patient was diagnosed according to history, chest radiograph, spirometry, high-resolution chest CT, and transbronchial lung biopsy. To identify the causative agent, cultured aeromolds were collected by the open-plate method. From the main fungi cultured, fungal antigens were prepared, and immunoblot analysis with the patient's serum and each fungal antigen was performed. A fungal colonies were isolated from the patient's home. Immunoblotting analysis with the patient's sera demonstrated a IgG-binding fractions to Penicillium species extract, while binding was not noted with control subject. This study indicates that the patient had hypersensitivity pneumonitis on exposure to Penicillium species in her home environment.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is caused by inhaled antigens that elicit lymphocytic inflammation in the peripheral airways and surrounding interstitial tissue of lung. HP is most often due to an occupational exposure (1-3). However, HP can be induced by exposure in a home environment to mould-contaminated air (4). Contamination of homes by Trichosporon cutaneum has been described with Japanese summer-type HP and heated swimming pool at home has also been associated with HP (5, 6). In Korea, there have been a few reports of HP caused by household exposure to Trichosporum cutaneum (7), Penicillium expansum (8), and Fusarium napiforme (9). In this paper, we report a case of HP caused by mold exposure (Penicillium species) in a home environment, which was confirmed by immunoblot analysis based upon Penicillium species isolated from the patient's home.

The patient was a 30-yr-old, non-smoking female housewife. She had been in excellent health. However, 2 months ago, she began to experience shortness of breath, coughing, and febrile sense at night and her symptoms were progressively aggravated. She has lived at old house for 8 months and the ceilings and walls of her bedroom, living room, and bathroom had been covered with moulds since 3 months ago. Initial physical examination showed inspiratory crackles in both basal lung fields. Her leukocyte count was 6,300/µL (neutrophil: 52.6%, lymphocyte: 33.8%, monocyte: 8.6%, eosinophil: 5%). On the chest radiograph, there were diffuse small nodular densities with increased haziness on both lower lung fields. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) revealed wide disseminated poorly defined nodules and ground glass opacities in both lung fields. Arterial blood gas analysis were pH of 7.43, PCO2 of 33 mmHg, PaO2 of 84.6 mmHg, HCO3 of 22.6 mM/L, and O2 saturation of 95.7%. Spirometry showed FVC of 2.2 L (60% predicted), FEV1 of 1.87 L (60 % predicted), FEV1/FVC of 85%, and DLCO of 7.23 mL per min/mmHg (28% predicted). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 44 mm/hr and complement C3 and C4 levels were normal. Serum IgG (872 mg/dL), IgA (297 mg/dL), and IgM (372 mg/dL) levels were normal. Skin prick tests with 80 common inhalant and food allergens showed all negative responses and total IgE by UniCap (Pharmacia, Upsala, Sweden) was 110 IU/mL. Sputum stainings for Mycobacterium tuberculosis were negative. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis revealed that lymphocytes were increased up to 89% of collected cells and CD4+/CD8+ ratio was reversed (0.19). The pathologic findings of specimens obtained by transbronchial lung biopsy demonstrated lymphocytic infiltration within alveolar wall and interstitium without an evidence of granuloma. At 5 day's admission, her symptoms were improved with corticosteroid therapy. Under the diagnosis of HP, she was advised to move to another house and take oral corticosteroid for 3 weeks. Her clinical symptoms, chest radiograph, and spirometry were normalized after 2 months.

Saboraud glucose agar (Difco, Detroit, MI, U.S.A.) plates containing 0.06 g/L of chloramphenicol were left open for 2 hr on floor in the patient's bedroom, living room and bathroom, and then incubated at 28℃ and 37℃ for 10 days. Colonies appearing on the plates were subcultured and identified morphologically.

Penicillium species was the predominant isolate (70-80 colonies per plate) from all sites of the air in the patient's home. A few colonies of Alternaria sp., Cladosporium sp., and Scopulariopsis sp. were noted.

Each fungal isolate was cultured in Saboraud glucose agar for 3 days and incubated in Czapek-Dox broth media (Sigma, St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Incubated broth media were kept at 37℃ for 4 days on a gyratory shaker. Fungal mycelia were separated from the broth media by passing through Whatmann filter paper. Mycelial extract was separated in liquid nitrogen containing sea sand. After shaking for 12 hr at 4℃ in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Triton X-100, the extract was separated again ultrasonically. The supernatant obtained through centrifugation and dialysis against distilled water was lyophilized.

SDS-PAGE was performed by the method of Laemmli (10). Mycelial extract antigens were dissolved in a sample buffer (Novex, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) and boiled for 5 min. Standard markers (3-185 kDa) (Novex, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) and antigens were applied to a Novex precast NuBis-Tris gel (4-12%) for the separation of fungal antigens. Electrophoresis was performed with a Novex X cell II mini-cell for 40 min at 200 constant voltage. The gel was fixed and stained with 0.1% Coomassie brilliant blue. By the method previously described by Tsang et al. (11), electroblotting was carried out for 60 min at 30V in Tris-glycine transfer buffer with 10% MeOH with a Novex X cell II blot module. After transfer, the nitrocellulose membrane was blocked with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 5% skim milk. The patient and control sera were diluted to 1:100 v/v with 5% skim milk/TBS. The membrane was then incubated with the patient and control sera for 1 hr at room temperature. It was then washed with TBS. Peroxidase-conjugated goat antihuman IgG was diluted to 1:1,000 with 5% skim milk/TBS and used as a secondary antibody solution. The membrane was then incubated with the secondary antibody for 1 hr at room temperature and washed again as above. To detect immobilized specific antibodies, enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (ECL, Amersham) was applied according to the instruction manual. Mixed an equal volume of detection solution 1 with detection solution 2, added to the protein site of the membrane and incubated for one min at room temperature. And then the membrane was exposed to the film in the film cassette for 10 sec and developed.

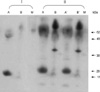

To determine the protein components of a fungal extract, the extract was analyzed by a 4-12% gradient SDS-PAGE. Fig. 1 demonstrates the binding of specific IgG in patient and control sera on the blotted nitrocellulose membrane. Only a band of 43 kDa was bound to Penicillium species extracts, while no specific binding was found in other fungal extract and sera from control subject.

Penicillium sp. have been reported to be responsible for HP in association with a variety of exposures to mould-contaminated wood work (12, 13). It has also been reported to cause HP in a cheese worker (14) and in an entomologist (15).

The diagnosis of HP requires a constellation of clinical, radiographic, physiologic, pathologic, and immunologic criteria, each of which is rarely pathognomic alone (16). In general, the environmental history often provides a clue as to the potential etiologic agent. In the study, episodes of recurrent fever with breathlessness, cough, and malaise that follow a home environmental exposure are typical of extrinsic allergic alveolitis. The chest roentgenogram showed ground glass-like appearances, CT showed interstitial pneumonia, and spirometry showed restrictive ventilatory impairment with decreased diffusion capacity. Moreover, the pathologic findings of a specimen obtained by transbronchial lung biopsy showed interstitial lymphocytic infiltration. All of these characteristics are consistent with the diagnosis of HP.

Inhaled mold spores could provoke production of specific antibodies. The detection of these antibodies plays an important role in the diagnosis of HP. Although Ouchterlony's double immunodiffusion is the classical test to investigate specific antibodies, other studies such as counterimmunoelectrophoresis, radioimmunoassay, ELISA, crossed radioimmunoelectrophoresis, or immunoblotting can also be used (17). This study describes a patient having clinical and immunological features of HP resulting from mould exposure (Penicillium sp.) in her home environment. Although we did not perform an inhalation challenge, many elements of the history and laboratory findings support the diagnosis of HP. In this study, Penicillium sp. was isolated from the patient's home environment and IgG immunoblotting demonstrated specific IgG-binding components to Penicillium sp. extract. The presence of serum specific IgG antibody to the Penicillium sp. antigen isolated from the patient's home provides additional support for the diagnosis of HP and suggests that Penicillium sp. was the causative agent.

In conclusion, this is a case of HP occurring in the home and caused by the fungus, Penicillium sp. This case report emphasizes the need to be aware of the clinical presentation of HP after mold exposure in a home environment.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Immunoblot analysis of fungal antigen from patient's home environment. IgG immunoblotting with sera of healthy control (I) and patient (II). Isolated fungal antigens are Alternaria sp. (A, A') and Penicillium sp. (B, B'). A' and B' serum collected 30 days after follow-up. Molecular size marker (M).

References

1. Erkinjuntti-Pekkanen R, Rytkonen H, Kokkarinen JI, Tukiainen HO, Partanen K, Terho EO. Long-term risk of emphysema in patients with farmer's lung and matched control farmers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998. 158:662–665.

2. Lee MW, Jung WJ, Lee JA, Lee JH, Choe KH, Kim MK. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis induced by oyster mushroom spores. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998. 18:84–89.

4. Do YK, Kim YJ, Kang HJ, Yu KS, Yun HJ, Jun JH, Lee BK, Song DY. A case of hypersensitivity pneumonitis by Alternaria as a suspected etiology. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2003. 54:338–345.

5. Park JW, Hong CS, Jee YK, Park JS, Lee KY, Kim KY, Jun Y, Hwang YJ, Oh HT, Lyu S. A case of hypersensitivity pneumonitis with positive precipitin antibody to Trichosporon cutaneum. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999. 19:969–973.

6. Moreno-Ancillo A, Vicente J, Gomez L, Martin Barroso JA, Barranco P, Cabanas R, Lopez-Serrano MC. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis related to a covered and heated swimming pool environment. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997. 114:205–206.

7. Yoo CG, Kim YW, Han SK, Nakagawa K, Suga M, Nishiura Y, Ando M, Shim YS. Summer-type hypersensitivity pneumonitis outside Japan: a case report and the state of the art. Respirology. 1997. 2:75–77.

8. Park HS, Jung KS, Kim SO, Kim SJ. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis induced by Penicillium expansum in a home environment. Clin Exp Allergy. 1994. 24:383–385.

9. Lee SK, Kim SS, Nahm DH, Park HS, Oh YJ, Park KJ, Kim SO, Kim SJ. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis caused by Fusarium napiforme in a home environment. Allergy. 2000. 55:1190–1193.

10. Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970. 227:680–685.

11. Tsang VC, Peralta JM, Simons AR. Enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot techniques (EITB) for studying the specificities of antigens and antibodies separated by gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 1983. 92:377–391.

12. Belin L. Clinical and immunological data on "wood trimmer's disease" in Sweden. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1980. 107:169–176.

13. van Assendelft AH, Raitio M, Turkia V. Fuel chip-induced hypersensitivity pneumonitis caused by Penicillium species. Chest. 1985. 87:394–396.

14. Campbell JA, Kryda MJ, Treuhaft MW, Marx JJ Jr, Roberts RC. Cheese worker's hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983. 127:495–496.

15. Solley GO, Hyatt RE. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis induced by Penicillium species. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1980. 65:65–70.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download