Abstract

Most of the interstitial lung diseases are rare, chronic, progressive and fatal disorders, especially in familial form. The etiology of the majority of interstitial lung disease is still unknown. Host susceptibility, genetic and environmental factors may influence clinical expression of each disease. With familial interstitial lung diseases, mutations of surfactant protein B and surfactant protein C or other additional genetic mechanisms (e.g. mutation of the gene for ATP-binding cassette transporter A3) could be associated. We found a 21 month-old girl with respiratory symptoms, abnormal radiographic findings and abnormal open lung biopsy findings compatible with nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis that is similar to those of her older sister died from this disease. We performed genetic studies of the patient and her parents, but we could not find any mutation in our case. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone and oral hydroxychloroquine were administered and she is still alive without progression during 21 months of follow-up.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is defined as a specific form of chronic fibrosing interstitial pneumonitis limited to the lung. It is a rare, chronic, progressive, usually fatal interstitial lung disorder (1-3). In children, interstitial pneumonitis (IP) presents with a wide spectrum of histologic abnormalities that usually do not fit the classification for IP used in the adult population (4). IP is a group of very rare diseases in childhood (5).

The familial form can be described, as IP occurred in at least two members of a family (2, 3, 6). The proportion of familial ILD is unknown, and a genetic basis of it is estimated to be 0.5-2.2% of cases (6). In approximately half of the clinically unaffected family members, it is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait with reduced penetrance but autosomal recessive pattern is not excluded (3, 6-8).

Although the etiology of the majority of ILDs is still unknown, there is increasing understanding of the cellular and cytokine interactions associated with inflammation and fibrosis. Host susceptibility, genetic factors and environmental cofactors may influence clinical expression of each disease (9). The inflammatory process of ILD begins with an initial injury to the alveolar and interstitial structures (alveolitis), which is followed by a stage of tissue repair and variable degrees of fibrosis, and an alveolar infiltrate with variable amounts of proteinaceous material (4, 10). The accumulation of proteinaceous material in the alveolar space is a characteristic finding in lung diseases associated with surfactant system abnormalities (4). There are reports that mutations in surfactant protein B (SP-B) and surfactant protein C (SP-C) are associated with familial usual interstitial pneumonitis in adults and with cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis (NSIP) in children (6). Recently, a mutation in the gene encoding the hydrophobic, lung-specific SP-C was discovered in association with a decrease in the level of SP-C in familial ILDs (4, 10, 11).

Here we report a very young Korean girl with symptoms and radiological findings of ILD similar to those of her older sister who died from this disease. Open lung biopsy showed that the patient had NSIP. Chest computed tomography (CT) scans of both sisters were compared and the findings, etiology and treatment of this disease are discussed.

A 21 month-old girl was brought to Asan Medical Center suffering fever, cough and tachypnea for 4 months. Abnormal lung findings were first noted by a chest radiography taken due to fever when she was 8 months old. No further evaluation was performed at that time. The symptoms of the patient at 21 months of age were the same as those that her sister had shown at age 4 yr.

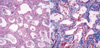

Physical examination of the patient revealed tachypnea at rest (beyond 60/min) and chest retraction without rales or wheezing, but no digital clubbing. On arrival at the hospital, the Denver symptom score (12) of ILD gave a value of 2 points meaning the patient showed respiratory symptoms but oxygen saturation was normal in room air under all conditions. Blood, urine, sputum and stool studies revealed no evidence of acute viral or bacterial infection. Neither virus (adenovirus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, cytomegalovirus) nor bacteria was found in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The chest radiography showed a dense hazy area at the central region of both lungs and blunting on the left costophrenic angle. Chest CT (Fig. 1A) demonstrated diffuse fibrosis on the medial portion of both lung fields and subpleural consolidation along both lateral pleura. Based on the similar findings from chest CT (Fig. 1B), the sister of the patient had been diagnosed with uncharacterized ILD, and died 5 months after diagnosis. Surgical open lung biopsy (Fig. 2) was performed at 22 months of age. A diagnosis of NSIP was made based on the findings of diffuse, uniform thickening of the interstitium with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and collagen fibrosis. Some alveoli contain accumulation of intra-alveolar macrophages, while some alveoli had hyperplastic type II alveolar pneumocytes. Genetic studies were performed with the lung biopsy specimens and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. These revealed no identifiable mutation in the genes encoding surfactant proteins. Examination of peripheral blood cells from the patient's parents also showed no evidence of mutations in these genes. The patient was treated with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg/day, 3 doses every other day, monthly) and oral hydroxychloroquine (daily).

During treatment, tachypnea and dyspnea on exertion were still evident and the Denver symptom score was 2 points at follow-up. Follow-up high resolution CT (HRCT) showed that there was no further disease progression after 21 months.

There have been previous reports of familial ILD, and infants with this disease can become symptomatic in the first 6 weeks of life (1). Such patients have tachypnea and respiratory distress with grunting, intercostal and subcostal retraction, and cyanosis. The mortality rate is high, especially in children younger than 1 yr (1). The ILD of unknown origin which was developed in the present patient's sister progressed quickly and she died at 4 yr of age, 5 months after she had been diagnosed.

Risk factors for ILD are virus (adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, influenza virus, cytomegalovirus), mycoplasma or other infectious agents, drugs, chronic aspiration, environmental factors like metal dust and wood dust, and genetic predisposition (5, 13). Given that investigations on the etiology of the present patient ruled out any environmental or infectious causes, we examined genetic factors. There were analyses of candidate loci near the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region of chromosome 6 to suggest a genetic basis for ILD in familial cases (6). In addition, an association has been established between interstitial pulmonary fibrosis and α1-antitrypsin inhibition alleles present on chromosome 14 (2). Recently, several investigators reported that multiple heterozygous mutations in the surfactant protein C gene were associated with ILD (10). Triggers such as infection or toxins may contribute to the wide diversity in clinical presentation of surfactant protein C gene-associated pulmonary fibrosis (6). In our case, the pathological findings were compatible with NSIP but we did not find a surfactant protein gene mutation in lung biopsy samples or peripheral blood cells from the patient, or in peripheral blood cells from her parents. There was a report of fatal respiratory diseases in full-term infants with symptoms of surfactant deficiency in whom a deficiency of surfactant protein B was excluded. It suggested that the mutation of the genes for ATP-binding cassette transporter A3 (ABCA3) that were involved in the transport of phospholipids and sterols could be associated with unexplained surfactant deficiency in full-term infants (14).

HRCT allows early diagnosis of ILD and commonly shows patchy, predominantly peripheral, subpleural, bibasilar reticular abnormalities (15). The extent of pulmonary infiltration on CT is an important predictor of survival (2). We had two similar HRCT images, one from the patient and the other from her sister whose disease had progressed further.

The diagnosis of ILD can be confirmed by open lung biopsy (16). The chronic pneumonitis in infancy is characterized by interstitial thickening with mesenchymal cells rather than inflammatory cells and by an alveolar infiltration with variable amounts of proteinaceous material (10, 15). The findings of the lung biopsy specimen from the present patient also showed mild, diffuse, and uniform thickening of the interstitium with mild fibrosis, consistent with the diagnosis of NSIP.

Corticosteroid administration (1, 16, 17) has been the mainstay of therapy for ILD, and chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine (1, 17) have also been used successfully in the treatment of childhood IP. However the exact mechanism of action of this treatment is unknown. For the present patient, treatment with methylprednisolone and hydroxychloroquine was initiated soon after ILD diagnosis due to her family history. The Denver symptom score was used to evaluate the symptoms, and continued use of this system indicated that patient's disease was not progressing during 21 months of follow-up.

In summary, we have described an infant with NSIP whose sibling died from a similar disease. The need of early diagnosis and treatment with corticosteroids in combination with hydroxychloroquine for the familial ILD could be considered. Trying to determine the etiology of the familial form of this disease is likely to result in better treatment for these patients.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Computed tomography (CT) scans of the patient (A) and the patient's sister (B), showing diffuse fibrosis and subpleural consolidations in both lungs. |

| Fig. 2Interstitial pneumonia with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and variable amount of collagen fibrosis resulted in the thickening of the interstitium. Most alveoli also show variable amount of intra-alveolar macrophage accumulation and hyperplasia of the alveolar pneumocytes. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin stain, ×100, (B) Masson's trichrome stain, ×100. |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. LM Nogee (Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, U.S.A.) for helping us with genetic studies of our patient and her parents.

References

1. Balasubramanyan N, Murphy A, O'Sullivan J, O'Connell EJ. Familial interstitial lung disease in children: response to chloroquine treatment in one sibling with desquamative interstitial pneumonitis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1997. 23:55–61.

2. American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000. 161:646–664.

3. Bitterman PB, Rennard SI, Keogh BA, Wewers MD, Adelberg S, Crystal RG. Familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence of lung inflammation in unaffected family members. N Engl J Med. 1986. 314:1343–1347.

4. Amin RS, Wert SE, Baughman RP, Tomashefski JF Jr, Nogee LM, Brody AS, Hull WM, Whitsett JA. Surfactant protein deficiency in familial interstitial lung disease. J Pediatr. 2001. 139:85–92.

5. Chernick V. Interstitial lung disease in children: an overview. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999. 27:Suppl 18. 30s.

6. Thomas AQ, Lane K, Phillips J III, Prince M, Markin C, Speer M, Schwartz DA, Gaddipati R, Marney A, Johnson J, Roberts R, Haines J, Stahlman M, Loyd JE. Heterozygosity for a surfactant protein C gene mutation associated with usual interstitial pneumonitis and cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis in one kindred. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002. 165:1322–1328.

7. Solliday NH, Williams JA, Gaensler EA, Coutu RE, Carrington CB. Familial chronic interstitial pneumonitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973. 108:193–204.

8. Hodgson U, Laitinen T, Tukiainen P. Nationwide prevalence of sporadic and familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence of founder effect among multiplex families in Finland. Thorax. 2002. 57:338–342.

9. Verleden GM, du Bois RM, Bouros D, Drent M, Millar A, Müller-Quernheim J, Semenzato G, Johnson S, Sourvino G, Olivier D, Pietinalho A, Xaubet A. Genetic predisposition and pathogenetic mechanisms of interstitial lung disease of unknown origin. Eur Respir J. 2001. 32:17–29.

10. Nogee LM, Dunbar AE III, Wert SE, Askin F, Hamvas A, Whitsett JA. A mutation in the surfactant protein C gene associated with familial interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2001. 344:573–579.

11. Whitsett JA, Weaver TE. Hydrophobic surfactant proteins in lung function and disease. N Engl J Med. 2002. 347:2141–2148.

12. Fan LL, Kozinetz CA. Factors influencing survival in children with chronic interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997. 156:939–942.

13. Stern RC. Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Idiopathic diffuse interstitial fibrosis of the lung. Nelson's Textbook of Pediatrics. 2003. 16th de. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders;1299.

14. Shulenin S, Nogee LM, Annilo T, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Dean M. ABCA3 gene mutations in newborns with fatal surfactant deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2004. 350:1296–1303.

15. Lee KS, Chung MP. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: clinical findings, pathogenesis, pathology and radiologic findings. J Korean Med Sci. 1999. 14:113–127.

16. Chung JH, Ha SJ, Kim BS, Hong SJ. Clinical spectrum and lung pathology in children with interstitial lung disease. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 2002. 45:79–87.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download