Abstract

Pulmonary metastases of uterine endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) are uncommon. The patterns of uterine ESS metastasis to the lung are multiple pulmonary nodules, single nodule, or cystic lesions. Pulmonary intraalveolar micronodular metastases of uterine ESS are unusual and have not been reported. We experienced a case of metastatic uterine ESS presenting as pulmonary diffuse micronodules with ground glass opacities on chest computed tomography of a 37-yr-old woman who previously underwent hysterectomy due to low grade ESS of the uterus four years ago. The histologic findings of video assisted thoracotomy biopsy showed numerous intraalveolar polypoid micronodules protruding from the alveolar septums. All tumor nodules were composed of short spindle cells arranged in ill-defined whorls, and nuclear feature and sparse cytoplasm were seen in uterine ESS. Immunohistochemically, these cells showed strong nuclear staining for estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor, and diffuse cytoplasmic staining for CD10.

Distant metastases of uterine endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) are uncommon. The most commonly affected site is the lung, with a reported incidence ranging from 7% to 28% (1). Multiple pulmonary nodules are common patterns of metastases of uterine ESS. Unusual presentations included bilateral spontaneous pneumothoraces with predominantly cystic lesions (2-4). Metastatic uterine ESS presenting as a solitary lung nodule is also unusual and only a few cases were documented histologically (1, 5). A case of bilateral reticulonodular infiltrates corresponding to a lymphangitic growth pattern was documented (1). We experienced a case of pulmonary metastases of uterine ESS that presented intraalveolar micronodules, which is a rare pattern of metastasis not described in English literature.

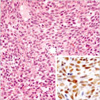

A 37-yr-old woman with increased extent of small random micronodules and ground glass opacities (GGO) in both lungs with dyspnea visited the hospital. She had been diagnosed with ESS in the uterus which had been removed due to postpartum bleeding 4 yr ago. One year later, both of her ovaries and vaginal stump were removed due to the recurred uterine ESS. At that time, chest computed tomography (CT) showed miliary pattern of micronodules in both lung fields with symptom of dyspnea American Thoracic Society (ATS) grade I. Chemotherapy with Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) protocol and ifosphamide were performed. During the 3 yr follow-up period, no significant change was found in pulmonary micronodular densities, but occasionally, GGO was found on chest CT with symptoms of dyspnea ATS grade II and fever (Fig. 1). These GGO and her symptoms improved after corticosteroid therapy and the nature of GGO was clinically regarded as alveolar hemorrhage or intraalveolar fibroblastic polyps. Video assisted thoracotomy biopsy was performed to evaluate the pulmonary micronodules and GGO. Under gross examination, numerous round or ovoid gray white sandlike granular lesions were apparent. Histologic sections showed numerous micronodules in the alveolar spaces (Fig. 2). These nodules consisted of short spindle cells arranged in ill-defined whorls and the neoplastic cells had bland nuclear features and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3). Mitotic figures were less than 2 per 10 high power fields. The histologic features of the lung nodules were identical to that of low grade uterine ESS obtained from hysterectomy specimen. Immunohistochemically, these neoplastic cells showed strong nuclear staining for estrogen receptor (Novocastra, Newcastle, U.K., 1:100 dilution) (Fig. 3, inset) and progesterone receptor (Novocastra, 1:40 dilution), and diffuse cytoplasmic staining for CD10 (Novocastra, 1:40 dilution). The patient was well and asymptomatic when last seen, 8 months post thoracotomy, and the GGO was improved with repeated tamoxifen and ifosphamide therapies.

ESS represents approximately 15-25% of all uterine sarcomas and are separated into high and low grades, depending primarily on the mitotic index (more or less than 10 mitoses per 10 high power fields, respectively). Low grade ESS is the most common and has a favorable prognosis. Recurrence is not uncommon and tends to be limited to the pelvis. Distant metastases may develop after long tumor-free intervals and the lung is the most commonly affected site. The most common growth pattern of pulmonary metastatic ESS, previously described in the literatures, is well circumscribed nodules with entrapped air spaces lined by non-neoplastic respiratory epithelium (1). The unusual growth patterns are solitary nodule, satellite with infiltrative margins, lymphangitic pattern and bilateral spontaneous pneumothoraces associated with predominantly cystic lesions mimicking lymphangioleiomyomatosis, which can contribute to the diagnostic dilemma (1-5). This is especially true if clinicians and/or pathologists are unaware of a prior diagnosis of uterine ESS. Prior misdiagnosis of a uterine tumor can also be misleading, emphasizing the need to review previous surgical specimens, particularly gynecologic specimen in female patients with unusual mesenchymal lung neoplasms (6, 7).

The micronodules of the present case did not show entrapped respiratory epithelium and were mainly located in the intraalveolar spaces growing out from alveolar walls suggesting hematogeneous spread. This pattern of metastases of uterine ESS is interesting and has been not reported in English literatures. We assumed that the lesions were caused by lodging of microtumor emboli through the pulmonary artery. The metastatic ESS demonstrated the same range of histologic features seen in primary uterine ESS.

The differential diagnosis includes benign metastasizing leiomyoma, sclerosing hemangioma, solitary fibrous tumor, hemangiopericytoma, and lymphangioleiomyomatosis in small biopsies. Immunohistochemical stains can be helpful in differentiation of above diseases. Immunostaining for estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor are positive in nearly all cases of uterine ESS. Immunostaining for keratin and smooth muscle markers are variable. Diffuse immunoreactivity for CD10 in uterine ESS can also be helpful in separating them from uterine smooth muscle neoplasms, which are usually negative.

Here, we report a case of unusual pulmonary metastatic uterine ESS in a 37-yr-old female with a diffuse micronodule and GGO on chest CT. Pulmonary metastases of low grade ESS may have an excellent prognosis and little effect on survival.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Aubry MC, Myers JL, Colby TV, Leslie KO, Tazelaar HD. Endometrial stromal sarcoma metastatic to the lung: a detailed analysis of 16 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002. 26:440–449.

2. Mahadeva R, Stewart S, Wallwork J. Metastatic endometrial stromal sarcoma masquerading as pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J Clin Pathol. 1999. 52:147–148.

3. Itoh T, Mochizuki M, Kumazaki S, Ishihara T, Fukayama M. Cystic pulmonary metastases of endometrial stromal sarcoma of the uterus, mimicking lymphangiomyomatosis: a case report with immunohistochemistry of HMB45. Pathol Int. 1997. 47:725–729.

4. Dines DE, Cortese DA, Brennan MD, Hahn RG, Payne WS. Malignant pulmonary neoplasms predisposing to spontaneous pneumothorax. Mayo Clin Proc. 1973. 48:541–544.

5. Satoh Y, Ishikawa Y, Miyoshi T, Mukai H, Okumura S, Nakagawa K. Pulmonary metastases from a low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma confirmed by chromosome aberration and fluorescence in-situ hybridization approaches: a case of recurrence 13 year after hysterectomy. Virchows Arch. 2003. 442:173–178.

6. Abrams J, Talcott J, Corson JM. Pulmonary metastases in patients with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Clinicopathologic findings with immunohistochemical characterization. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989. 13:133–140.

7. Chang KL, Crabtree GS, Lim-Tan SK, Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR. Primary uterine endometrial stromal neoplasms. A clinicopathologic study of 117 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990. 14:415–438.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download