Abstract

The pathogenic mechanism of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and aplastic anemia are associated with immunologic events which lead to glomerular cell injury or hematopoietic cell destruction. We present an extremely rare case of FSGS with aplastic anemia in a 30-yr-old woman. The laboratory examination show-ed hemoglobin 7.2 g/dL, white blood count of 4,200/µl, platelet count 70,900/µl. Proteinuria (2+, 3.6 g/day) and microscopic hematuria were detected in urinalysis. The diagnosis of FSGS and aplastic anemia were confirmed by renal and bone marrow biopsy. She was treated with immunosuppressive therapy of prednisone 60 mg/day orally for 8 weeks and cyclosporine A 15 mg/kg/day orally. She responded with gradually improving her clinical manifestation and increasing peripheral blood cell counts. Prednisone was maintained at the adequate doses with tapering after 8 weeks and cyclosporine was given to achieve trough serum levels of 100-200 ng/mL. At review ten month after diagnosis and initial therapy, the patient was feeling well and her blood cell counts increased to near normal (Hb 9.5 g/dL, Hct 32%, WBC 8,300/µl, platelet 123,000/µl) and renal function maintains stable with normal range proteinuria (0.25 g/day).

Immunosuppressive agents are the major therapy in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and in aplastic anemia, and therefore it generally believed that immunological mechanisms contribute to both diseases. The pathogenesis of FSGS is unknown but appears to be the result of a lymphokine or cytokine, which leads to glomerular epithelial cell injury resulting in segmental scar formation and finally glomerular destruction (1, 2). Aplastic anemia is manifested as a reduction in the number of pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells, but, why this occurs is still uncertain. Some of the causes include abnormalities of the hematopoietic stem cells, abnormalities in the hematopoietic microenvironment, and immunologically mediated damage to the hematopoietic stem cells (3, 4). Although immune pathophysiology might influence on each disease mechanism, a MEDLINE review of the literature notices there is no previous description involving FSGS with aplastic anemia. Here, we report a case of FSGS associated with aplastic anemia, and summarize the literature in this setting.

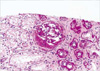

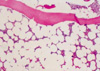

A 30-yr-old woman was admitted to this hospital with symptoms of general weakness and generalized edema lasting for 3 weeks. She had no previous history of drug, chemical exposure, radiation, or infection. The physical findings included pale conjunctiva, marked pretibial edema, and a blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg. A peripheral blood count showed hemoglobin 7.2 g/dL, hematocrit 20.7%, corrected reticulocyte count 0.8%, white blood count of 4,200/µL (39% polymorphonuclear cells, 45% lymphocytes, 12% monocytes), and platelet count 70,900/µL. In blood smear, normochromic, normocytic anemia without polychromatophilia was found, no schistocytes were present, and white cells and platelets were decreased without abnormal cells. The direct Coombs test was negative. Proteinuria (2+, 3.6 g/day) and microscopic hematuria were detected by urinalysis. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was 25 mg/dL, creatinine 0.8 mg/dL, serum cholesterol 292 mg/dL and serum protein 7.0 g/dL with albumin 3.2 g/dL. Serum electrolytes and serum IgG, IgM, and IgA were unremarkable. A renal ultrasound found normal sized and echogenic kidneys in each. A percutaneous renal needle biopsy was taken four days after admission. Twenty-two glomeruli were present in the specimen for light microscopy. Kidney biopsy revealed obliteration of the glomerular capillary lumen in segmental parts of some of the glomeruli (12%), establishing the diagnosis of FSGS (Fig. 1). Tubules exhibited focal moderate to severe atrophy or loss with interstitial fibrosis and mononuclear cell infiltration. Blood vessels were unremarkable. The immunofluorescence revealed segmental IgM deposits in one of the visualized glomeruli. Electron microscopy showed marked foot process fusions of the podocytes in a microscopically normal glomerulus. Simultaneously, we performed a bone marrow (BM) biopsy for pancytopenia study. Biopsy confirmed severe hypocellular BM (10%), with increased fatty areas and a few hematopoietic cells with normal appearance, and negative cytogenetic studies (Fig. 2). Finally, we diagnosed FSGS associated with mild aplastic anemia. In addition, we excluded any other secondary causes of FSGS and aplastic anemia. No clinical or serological evidence for parvovirus B19, Ebstein Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B or C infection and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was obtained. Other immunological tests showed C3 112 mg/dL (normal 62-99 mg/dL), C4 32.5 mg/dL (normal 19-36 mg/dL) and antinuclear antibody or RA factor within the normal range. Furthermore, there was no radiological evidence for reflux nephropathy or renal agenesis.

She was treated with immunosuppressive therapy of prednisone 60 mg/day orally for 8 weeks and oral cyclosporine 15 mg/kg/day. Additionally, supportive therapy including ACE inhibitor and protein restriction (<0.8 g/kg/day) were given. After 2 months, she responded with gradually improving her clinical manifestation and increasing peripheral blood cell counts. Prednisone was maintained at the adequate doses with tapering after 8 weeks but cyclosporine was given sufficient to achieve trough serum levels of 100-200 ng/mL. No cyclosporine-associated toxicity occurred. At review ten month after diagnosis and initial therapy, the patient was feeling well and her blood cell counts increased to near normal (Hb 9.5 g/dL, Hct 32%, WBC 8,300/µL, platelet 123,000/µL) and renal function maintained stable (BUN 22 mg/dL, creatinine 1.0 mg/dL) with normal range proteinuria (0.25 g/day).

FSGS is a clinicopathological disease defined by the presence of proteinuria and by segmental glomerular scars involving some glomeruli. Primary FSGS accounts for 7-20% of glomerular lesions in patients presenting with nephrotic syndrome (5, 6). Since the pathogenesis and treatment for primary and secondary FSGS may differ significantly, secondary causes associated with FSGS such as infection with HIV, heroin abuse and reflux nephropathy must be excluded before making the diagnosis of primary FSGS (2).

Aplastic anemia is manifested as a marked reduction in the number of pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells, but why this occurs is still uncertain. Some of the proposed pathogenic mechanisms include intrinsic defects of hematopoietic stem cells, defects in the marrow microenvironment, and abnormal humoral or cellular immune control of hematopoiesis (3, 4, 7). Aplastic anemia is occasionally associated with renal diseases such as, chronic renal failure, chronic glomerulonephritis or nephrotic syndrome. Glomerular involvement is mainly caused by parvovirus B19 with or without renal allograft, organic solvent exposure or autoimmune diseases (8, 9). In particular, in aplastic anemia combined with an autoimmune disease, some reports showed that eosinophilic fasciitis, glomerulonephritis, thymoma or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) were associated with aplastic anemia (10).

Though the association between glomerulonephritis and aplastic anemia has yet not been well established, immunosuppressive agents are often effective in treating FSGS and aplastic anemia. Thus, it is now believed that immunological mechanisms contribute to the disease, with active destruction of blood-forming cells by lymphocytes. Cases have been reported in which cytotoxic T cell clones that damage the autologous hematopoietic precursor cells are present and some have suggested that T cell dysfunction may play a role in the pathogenesis of the glomerular lesion (11). Other proposed mechanisms include the production of circulatory 'permeability' factor (s), possibly cytokines or lymphokine (IFN-γ, TNF) or related substances that could suppress hematopoietic cell proliferation and increase glomerular membrane permeability, resulting in epithelial cell injury, segmental scar formation and ultimately glomerular obsolescence. The aberrant immune response may be triggered by environmental exposure to chemicals, drugs or viral infections, and perhaps, to endogenous antigens generated by genetically altered BM cells (2, 12).

In the case described here, the clinical and pathological features led to a diagnosis of FSGS coexistent with aplastic anemia. In this case of both FSGS and aplastic anemia, each disorder is occasionally associated with autoimmune disease, such as SLE or rheumatoid arthritis (10). Also, although a renal biopsy was not performed, a case was reported by Park et al. that aplastic anemia and nephrotic syndrome was simultaneously diagnosed in SLE (13). In our opinion, this case is suggested that direct immune mechanism, i.e., involving cytotoxic T cells and cytokines, influences both diseases and there was no trigger factor, such as drug and chemical exposure or viral infection.

The treatment of FSGS and aplastic anemia are controversial issues, mostly immunosuppressive therapies and conservative treatments have been used (3, 8, 14). Response to immunosuppressive therapy would suggest a causative or perpetuating role for autoimmunity in the development of these diseases. In aplastic anemia, treatment with immune suppression (cyclosporine A±anti-lymphocyte globulin) and BM transplantation has improved the response rates and survival of patients (3, 8). In fact, various immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroid, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or cyclosporine A have been used in the treatment of FSGS. However, among them, only cyclosporine A is an effective immunosuppressive drug in aplastic anemia. So, in our case, we decided to use high-dose corticosteroids and cyclosporine A and added ACE inhibitors combined with diet therapy for anti-proteinuric effect. At the present time, she is in the ten month of follow-up and her blood cell count increases near to normal and serum creatinine remains stable with near normal proteinuria.

In summary, we describe a rare report showing an association between FSGS and aplastic anemia. Our observations suggest that immune mechanism including T lymphocytes and cytokines could play a role in the development of FSGS and aplastic anemia.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Savin VJ, Sharma R, Sharma M, McCarthy ET, Swan SK, Ellis E, Lovell H, Warady B, Gunwar S, Chonko AM, Artero M, Vincenti F. Circulating factor associated with increased glomerular permeability to albumin in recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1996. 334:878–883.

2. Korbert SM. Clinical picture and outcome of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999. 14:Suppl 3. 68–73.

4. Teramura M, Mizoguchi H. Special education: aplastic anemia. Oncologist. 1996. 1:187–189.

5. Beaufils H, Alphonse JC, Guedon J, Legrain M. Focal glomerulosclerosis: natural history and treatment. Nephron. 1978. 21:75–85.

6. Haas M, Spargo BH, Coventry S. Increasing incidence of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis among adult nephropathies: a 20-year renal biopsy study. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995. 26:740–750.

7. Young NS, Maciejewski J. The pathophysiology of acquired aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 1997. 336:1365–1372.

8. Taylor G, Drachenberg C, Faris-Young S. Renal involvement of human parvovirus B19 in an immunocompetent host. Clin Infect Dis. 2001. 32:167–169.

9. Weiss AS, Markenson JA, Weiss MS, Kammerer WH. Toxicity of D-penicillamine in rheumatoid arthritis. A report of 63 patients including two with aplastic and one with the nephrotic syndrome. Am J Med. 1978. 64:114–120.

10. Stebler C, Tichelli A, Gratwohl A, Dazzi H, Nissen C, Steiger U, Speck B. Aplastic anemia combined with an autoimmune disease (eosinophilic fascitis or glomerulonephritis). Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1991. 121:873–876.

11. Moebius U, Herrmann F, Hercend T, Meuer SC. Clonal analysis of CD4+/CD8+ T cells in a patient with aplastic anemia. J Clin Invest. 1991. 87:1567–1574.

12. Fiser RT, Arnold WC, Charlton RK, Steele RW, Childress SH, Shirkey B. T-lymphocyte subsets in nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int. 1991. 40:913–918.

13. Park JW, Choi SY, Kim HS, Nam DK, Kim HC, Kim HY, Park HS, Nahm DH. Plasmafiltration and synchronized cyclophosphamide therapy in SLE with aplastic anemia. Korean J Intern Med. 1999. 56:129–133.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download