Abstract

We present a Korean case of Hirayama disease with its typical neuroradiological findings of forward displacement of cervical dural sac and compression of the lower cervical cord during neck flexion. A 15-yr-old boy was presented with a one-year history of progressive weakness and atrophy affecting bilateral hands and forearms. The electrodiagnostic findings were compatible with the lesion of the anterior horn cells at the C7, C8, and T1 spinal segments. With neck flexion, cervical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the anterior shifting of the lower cervical dural sac resulting in the cord compression of those segments. Presumably, this disease might have been prevalent in Korea frequently under the diagnosis of "benign focal amyotrophy". In this regard, we discuss the clinical importance of cervical MRI with neck flexion and anticipate the increasing reports of the case substantiated by its characteristic radiological features.

Juvenile muscular atrophy of distal upper extremity, also known as Hirayama disease, has been reported mainly in Asian countries such as Japan, India, Taiwan as well as Korea (1-7). Juvenile muscular atrophy of distal upper extremity is a type of localized motor neuron disease involving predominantly the seventh and eighth cervical, and the first thoracic spinal segments of the distal upper extremities either unilaterally or bilaterally in an asymmetric manner. This disorder, mostly non-familial, is developed in the late teens or early twenties with male preponderance, and typically exhibits an insidious onset, slow progression, and often a self-limiting course.

Although several articles about the patients with the identical features have been reported in Korea (4-7), they have merely dealt with the clinical features of the disease without describing its nearly pathognomonic radiological findings at neck flexion posture. Here, we present an illustrative case of Hirayama disease with its diagnostic magnetic resonance image (MRI), and discuss its clinical implication.

A 15-yr-old boy complained of a one-year history of slowly progressive weakness of the right hand and forearm, which worsened in cold weather. He also sensed intermittent fasciculations in the right-hand and forearm muscles. Besides, he suffered from coarse hand tremor, particularly when writing. Quite recently, he has noted the weakness of the other hand of a similar nature. He has been very athletic in sport activities like basketball, and has grown as much as 30 cm (1 foot) in height over the past two years. His medical history was non-contributory, and he denied any allergic disease. None of his family members reported having similar symptoms.

A neurological examination revealed that he had a bilateral atrophy of intrinsic hand muscles and forearm muscles except for the brachiradialis, and the atrophy was worse in the right hand. However, the weakness was noted only in the right hand and forearm on manual muscle testing (MRC grade IV+) including elbow extension. The other muscles, including the brachioradialis, were normovolemic and exhibited normal power, referred to as "oblique" amyotrophy. The tendon reflexes were normal with flexor plantar responses from both sides. Cranial nerve functions were normal as well. No ataxia, or sensory disturbances, or extrapyramidal signs were noted.

Motor nerve conduction studies of the right median and ulnar nerves, which were recorded at abductor pollicis brevis and abductor digitii minimi, showed normal motor nerve conduction velocities (54 and 59 msec over the segment between wrist and elbow, respectively). CMAP amplitudes were still in the normal range (5.8 and 8.4 mV, respectively) in spite of the atrophy of those recording muscles. But terminal latencies were 4.0 and 3.4 msec when normal limits were 3.6 and 2.5 m/sec, respectively; and F-wave latencies, 29.4 and 33.3 msec when normal limits of both nerves were 28 msec. The measurements in the motor nerve conduction studies of the left arm exhibited the similar features, excepting that the left arm was less affected. Sensory nerve conduction studies of the bilateral median, ulnar, medial, and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerves showed normal conditions. Electromyography illustrated actively denervated and reinnervated patterns in the bilateral triceps brachii, pronator teres, extensor digitorum communis, first dorsal interosseus, or abductor pollicis brevis. Muscles innervated by the fifth and sixth cervical roots, such as the brachioradialis, biceps brachii, or deltoid - as well as lower extremity muscles and the tongue - showed a normal electromyographic pattern. These clinical and electrophysiological findings were suggestive of either anterior horn cell degeneration or root lesions involving the seventh and eighth cervical and first thoracic segments of the cord.

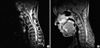

Simple cervical spine radiographs showed neither abnormalities with the exception of a loss of physiologic lordosis, nor a misalignment of the vertebral bodies in the flexed neck position (not shown). T1- and T2-weighted cervical MRI in the neutral position were unremarkable with normal contour and signal intensity of spinal cord (Fig. 1, 3A). With the neck flexion, sagittal and axial cervical MR images showed an anterior shifting of the posterior wall of the cervical dural sac below the third cervical vertebral level compressing the cervical spinal cord from the fifth cervical to the first thoracic vertebral levels (Fig. 2A). The anterior-posterior diameter of the spinal canal was reduced to about 30% of that in the neutral position. On enhancement, the widened posterior epidural space displayed a homogeneous strong enhancement with some signal flow void, suggesting a passively widened epidural venous plexus (Fig. 2B). The sixth and seventh cervical spinal segments were dynamically compressed when the patient flexed his neck forward, and the compression was more pronounced on the right side than on the left (Fig. 3B).

After confirming the compression of cervical cord on neck flexion, motor evoked potentials as well as median and posterior tibial somatosensory evoked potentials were performed both in anteflexion and in the neutral position of the neck. The results were turned out normal without a consistent latency prolongation between these two positions (central motor conduction time [CMCT] in the right abductor digitii quintii=8.1 and 8.6 msec, respectively; CMCT in the right abductor hallucis=16.9 and 16.6 m/sec, respectively).

Since the initial evaluation, two years have elapsed and no further progression has been noticed until now.

First of all, it would be helpful to comment about the nomenclature for this disease. This disease has been called many different names: juvenile asymmetric segmental spinal muscular atrophy (2), segmental muscular atrophy of distal upper extremity with juvenile onset (14), monomelic amyotrophy (15), and benign focal amyotrophy (16). Most of these names refer to the same disease, and the diagnoses have been made on the basis of its clinical features. Meanwhile, the "monomelic amyotrophy" and "benign focal amyotrophy" include the patients also with lower extremity onset, which would have different pathomechanism. Considering the characteristic radiological features as demonstrated in many reported cases including the present one, it seems to be rational to deal with the cases of either upper or lower extremity involvement differentially.

Since its first description by Hirayama in 1959 (1), most cases were reported in East Asia, though occasional cases were reported in the rest of the world. Most of the elucidation of its pathomechanism is attributable to the advent of MRI. It is generally accepted that Hirayama disease is due to compression of the lower cervical spinal cord by the posterior dural sac on neck flexion, leading to microcirculatory changes in the territory of the anterior spinal artery (2, 3, 8, 9). The non-specific ischemic lesions were observed in the anterior portion of the spinal cord at autopsy (10). Toma and Shiozawa proposed the disproportionate shortening of the dorsal roots as the cause of the anterior displacement of the lower cervical cord, which would be accentuated during the juvenile growth spurt (11). The history of striking height growth spurt (30 cm in two years) as shown in the above case supports the hypothesis presented by Toma and Shiozawa. There are a few reports arguing that Hirayama disease is a form of intrinsic motor neuron disease rather than flexion-induced amyotrophic cervical myelopathy (12, 13). These reports pointed out the absence of flexion-induced cord compression in the subjects of the studies. But it is noteworthy that more than 10 yr have passed since the onset of the disease in most patients in the studies. By the time more than 10 yr have passed, the dynamic forward displacements of the dural sac were reported to lessen or even disappear naturally (8). Therefore, the mere absence of the cord compression cannot substantiate as a proof against the "flexion-induced cervical compressive myelopathy" hypothesis.

It can be said that this disease might have been prevalent also in Korea, judging from the several reports regarding "benign focal amyotrophy" in Korea (4-7). But since the authors of these reports included patients with lower extremity onset in their studies, we suspect that they may have intended to present the clinical characteristics of the patient group with overall non-progressive segmental amyotrophy, rather than to identify the specific features of Hirayama disease. On the whole, the forty-one cases reported in these articles exhibited the typical clinical manifestations of Hirayama disease. Yet, its causative mechanisms were not identifiable without performing cervical MRI in the anteflexed neck position, even though the cervical MRI in the neutral position displayed a focal spinal cord atrophy in the sixth and/or seventh cervical segments in some patients with upper extremity involvement. Therefore, this case can serve as the first documented one of Hirayama disease in Korea with its characteristic cervical MRI of dynamic cord compression, emphasizing the clinical utility of the cervical MRI with neck flexion for the diagnosis of the patients with the characteristic clinical features. Specifically in this case, we performed motor and sensory evoked potential with the change of the neck position, that is, both with and without the cervical cord compression, suspecting the transient and reversible compromise of central conduction pathway. The absence of the consistent change in the latency between the neutral and flexed neck position might imply insufficient functional compromise of the sensorimotor central conduction pathway detectible by evoked potential studies or even no compromise at all, even at the face of cord compression with neck flexion. This result is thought to be in accordance with the absence of long tract sign or sensory change in the present case.

In conclusion, the dynamic cervical cord compression with neck flexion should be sought thoroughly with the cervical MRI in the cases of the characteristic clinical features. And we anticipate that an increasing number of the Korean cases of Hirayama disease would be presented substantially with its characteristic radiological features in the near future.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

T2-weighted sagittal images in the neutral position reveals normal contour and signal intensity along the sixth to the eighth cervical segments without cervical cord compression.

Fig. 2

(A) On T2-weighted sagittal images in the anteflexed position, there is an anterior shifting of the posterior wall of the cervical dural sac below the third cervical vertebral level compressing the cervical spinal cord from the fifth cervical to the first thoracic vertebral levels (row of white arrows). (B) On enhancement, the widened posterior epidural space shows a homogenous strong enhancement with some signal flow void, suggesting a passively widened epidural venous plexus.

Fig. 3

(A) The T1-weighted axial image of the sixth cervical cord segment in the neutral position has a normal appearance. (B) There is a striking forward compression by the posterior dural sac in the enhanced axial image of the same cervical cord segment in the anteflexed position (white arrowheads).

References

1. Hirayama K, Toyokura Y, Tsubaki T. Juvenile muscular atrophy of unilateral upper extremity; a new clinical entity. Psychiatr Neurol Jpn. 1959. 61:2190–2197.

2. Pradhan S, Gupta RK. Magnetic resonance imaging in juvenile asymmetric segmental spinal muscular atrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1997. 146:133–138.

3. Chen CJ, Chen CM, Wu CL, Ro LS, Chen ST, Lee TH. Hirayama disease: MR diagnosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998. 19:365–368.

4. Choi IS. Two cases of juvenile muscular atrophy confined to upper limb. J Korean Med Assoc. 1982. 25:669–670.

5. Choi IS. Benign focal amyotrophy. J Korean Med Assoc. 1987. 30:1371–1374.

6. Cheong KH, Cho PZ, Sunwoo IN, Park YK, Lee SA, Kim KW, Park KD. Clinical characteristics of benign focal amyotrophy. Korean J Neurol. 1992. 10:447–456.

7. Kim JY, Lee KW, Roh JK, Chi JG, Lee SB. A clinical study of benign focal amyotrophy. J Korean Med Sci. 1994. 9:145–154.

8. Hirayama K, Tokumaru Y. Cervical dural sac and spinal cord in juvenile muscular atrophy of distal upper extremity. Neurology. 2000. 54:1922–1926.

9. Kohno M, Takahashi H, Yagishita A, Tanabe H. "Disproportion theory" of the cervical spine and spinal cord in patients with juvenile cervical flexion myelopathy-a study comparing cervical magnetic resonance images with those of normal controls. Surg Neurol. 1998. 50:421–430.

10. Hirayama K. Juvenile muscular atrophy of distal upper extremity (Hirayama disease): Focal cervical ischemic poliomyelopathy. Neuropathology. 2000. 20:S91–S94.

11. Toma S, Shiozawa Z. Amyotrophic cervical myelopathy in adolescence. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995. 58:56–64.

12. Schroder R, Keller E, Flacke S, Schmidt S, Klockgether T, Schlegel U. MRI findings in Hirayama's disease: flexion-induced cervical myelopathy or intrinsic motor neuron disease? J Neurol. 1999. 246:1069–1074.

13. Robberecht W, Aguirre T, Van Den Bosch L, Theys P, Nees H, Cassiman JJ, Matthijs G. Familial juvenile focal amyotrophy of the upper extremity (Hirayama disease): Superoxide dismutase 1 genotype and activity. Arch Neurol. 1997. 54:46–50.

14. Saito M. Segmental muscular atrophy of distal upper extremity with juvenile onset. J Nagoya Med Assoc. 1977. 99:82–112.

16. Adornato BT, Engle WK, Kucera J, Bertorini TE. Benign focal amyotrophy. Neurology. 1978. 28:399.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download