INTRODUCTION

Subcutaneous emphysema of the leg is usually associated with gas gangrene following major trauma. However, intraabdominal disease may rarely cause subcutaneous emphysema, which may occur secondary to perforation of the gastrointestinal tract. It is uncommon that the lower extremity is involved in such a process. We were prompted to report our patient and to discuss the etiology, mechanisms, anatomical pathway and treatment.

CASE REPORT

A 38-yr-old man was admitted to the emergency department with a history of pain and swelling of the right thigh of 3 days duration. On admission, his temperature was 39℃, blood pressure 100/60 mmHg, and pulse rate 105/min. A physical examination revealed a painful swelling of the right thigh with subcutaneous crepitus, but tenderness and heat sense were not prominent, and there was no external wound or trauma history. Laboratory studies showed a WBC count of 35,500/µL, CRP 30.0 mg/dL, and an ESR 120 mm/hr. A roentgenogram of the lower extremity demonstrated massive air shadow in the soft tissue (Fig. 1).

Gas gangrene was suspected, accordingly, the patient was given a large dose of penicillin and an emergency operation was performed. No pus collection and no myonecrosis was found on operation, but a large amount of gas was drained and a pseudomembrane was found in the fascia of the thigh. Fasciotomy of the thigh and calf and a microbiologic examination were performed. The Gram-negative intestinal organism (Rahnella aquatilis) was obtained on culture. Three days after the operation, we detected the drainage of fecal materials from the inguinal area of the operation wound. On history re-taking, we found that the patient had received treatment for an ulceration of the rectum one year previously.

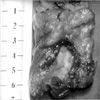

We carried out a barium enema study of the colon and rectum and found a fistula tract from the upper rectum to the thigh (Fig. 2). Sigmoid colonoscopy was done immediately, and the presence of a rectal lesion confirmed by colonofibroscopy, which revealed an ulceroinfiltrative lesion on the rectum about 8×9 cm in size. On biopsy, the lesion was confirmed to be a nonspecific ulceration. Accordingly, a low anterior resection of the fistular mass was performed (Fig. 3). Fecal materials were no longer drained, and the fasciotomy wound was covered with a split thickness skin graft. The patient was discharged three months after admission with a good general condition.

DISCUSSION

The term 'subcutaneous emphysema' has been used, because air or gas is found within the soft tissue (1). Subcutaneous emphysema of the leg is usually associated with gas gangrene following major trauma. However, intra-abdominal disease may only rarely cause subcutaneous emphysema, which may occur secondary to perforation of the gastrointestinal tract. It is uncommon that the lower limb be involved in such a process. Oetting et al. (2) reviewed the literature and documented 36 cases of subcutaneous emphysema originating from a gastrointestinal tract perforation, and only one of these cases reported subcutaneous emphysema of the leg. Shaffer (3) documented 16 cases reported subcutaneous emphysema of the leg arising from gastrointestinal tract perforations in the world literature from 1932 to 1968. Jager et al. reported 3 cases of subcutaneous emphyseam of the lower extremity only one case of which was caused by perforation of the sigmoid colon (1).

In many cases, the prior history and presenting symptoms have not clearly indicated an intra-abdominal origin, and this has often created serious diagnostic problems.

The most common misdiagnosis has been gas gangrene. The prominence of symptoms and signs in an extremity, coupled with meager abdominal or gastrointestinal symptoms and signs, account for these failures (3-5).

Radiologically, air shadow of the soft tissues extends down along the fascial planes between the muscles, which should alert the surgeon of the possibility of a gas gangrene, in which the gas is found in the muscle. Moreover, if the muscle is found to be viable during surgery, the diagnosis of gas gangrene can be practically ruled out (2, 6, 7). Instead, the possibility of a retroperitoneal perforation of the gastrointestinal tract should be suspected. Barium-enema studies and rectosigmoidoscopic examination will usually establish the correct diagnosis. Carcinoma of the colon, diverticulitis, and appendicitis are the most common causes. Other causes include traumatic perforation of the rectum, perforation of the terminal ileum due to foreign body ingestion, ischiorectal abscess, periureteral abscess perforating the cecum, and Crohn's disease (1, 2, 7, 8). The pathways of extrapelvic spread of disease to the lower extremity are discussed by Meyers and Goodman (9). These pathways of disease spread are related to the insertions and fascial investments of the psoas major and iliacus muscles below the inguinal ligament on the lesser trochanter, the pyriformis muscle, through the greater sciatic foramen on the greater trochanter, and the obturator internus muscle, through the lesser sciatic foramen on the greater trochanter. Another important pathway is along the course of the branches of the internal iliac vessels that penetrate the pelvic fascia to reach the gluteal region, particularly the superior gluteal artery that courses through the greater sciatic foramen. Though uncommon, the pelvic floor may be penetrated via the anterior abdominal wall.

The underlying condition of subcutaneous emphysema of the leg is serious. When caused by gastrointestinal perforation and fistulous tract formation, or by direct spread of abscesses, the mortality rate is about 50%. Moreover, in cases of spontaneous myonecrosis the mortality rate is 80% (5, 6). Therefore, prompt diagnosis is important if therapy is to have an chance of success. An aggressive treatment plan is imperative. In addition to the established supportive measures, a wise choice of antibiotics is important, and the enteric Gram-negative flora and specifically the anaerobic group, should be covered. This usually requires the simultaneous use of two or three antibiotics. Prompt attention should be given to the nutritional status of these patients, and intravenous hyperalimentation or tube feedings should be considered. Surgically, in addition to wide incision and drainage, fasciotomies and a diverting colostomy are mandatory.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download