Abstract

Endoscopic hysterectomy is increasingly selected as a current trend to minimize invasion, tissue trauma and early recovery. However it has disadvantages of the difficulty to learn and needs expensive equipments. So we developed a new minimally invasive method of vaginal hysterectomy-minilaparotomically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (MAVH) in order to complement the current laparoscopic surgery. The principle of MAVH is based on suprapubic minilaparotomical incision and uterine elevator that allows access and maximal exposure of the pelvic anatomy and an easy approach to the surrounding anatomy enabling division of round ligaments, Fallopian tubes, tuboovarian ligaments, and dissection of bladder peritoneum. After then, the vaginal phase of MAVH is done by the traditional vaginal hysterectomy. We enrolled 75 consecutive cases and in 73 cases thereof MAVH was accomplished successfully. The technique of MAVH is simple and easy to learn and it involves a small incision causing less pain and complications. This practice does not require expensive equipments. MAVH is considered as a safe and effective alternative method for abdominal hysterectomy in most cases.

Hysterectomy is one of the most frequent operations in the field of gynecology. According to the 1997 report by the Bureau of Statistics, U.S.A., 604,121 hysterectomies were performed. Among them, 64.5% were transabdominal hysterectomy (TAH), and the remaining 35.5% were vaginal hysterectomy (VTH) (1). VTH involves less pain and complications with fast recovery and bowel function (2), whereas the TAH frequently involves complications with slow recovery requiring longer hospitalization (3, 4). Due to these merits, VTH has been preferred whenever there was no contraindications against VTH or TAH (5).

There is no clearly established instruction for choosing a method of hysterectomy. However, the decisions are largely made based upon the surgeon's preference, experience, and subjective point of view (6, 7). The only official opinion suggested by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) is just the size of the uterus as a criterion in making a decision among the methods of hysterectomy. The ACOG suggests to choose VTH when the size of the uterus is smaller than that of 12 weeks pregnancy (280 g), and when the case is a benign disease with the lesion confined in the uterus flexible enough to allow downward movement (8), also referring to the patient's anatomical condition and preference, and the surgeon's level of expertise (9).

The method of hysterectomy should be chosen based on a more objective judgment rather than on a subjective point of view. In this context, a variety of minilaparotomical operations, particularly, laparoscopy-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) is being recognized as a possible alternative of TAH, thus practically reducing TAH (10). However, the LAVH entails a few problems: it requires an expensive equipment, a long learning course, and a good and well equipped operation room setup (11, 12).

Given this, the authors have developed a method of minilaparotomically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (MAVH), which is simple and easy to learn, and studied its safety and effectiveness.

The analysis of the safety and effectiveness of MAVH is based on 75 patients who received the operation from February 1, 2002 to July 10, 2002 in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Gachon Medical University Hospital in Korea.

The subjects were confined to those who had a benign disease that is also suitable for TAH, excluding uterine prolapse. Every patient who met this criterion was included in this study without purposeful selection. For diagnosis, we performed pelvic examination, ultrasonic examination, and general laboratory tests.

Every patient was given the precautions before operation. The enema was given before the day of operation and in the morning of the day of operation, and prophylactic antibiotics were given preoperatively. The operations were performed by the same surgeons.

The items on the checklist included the followings; patient's age, weight, body mass index, obstetrical history, previous pelvic operation history, preoperative diagnosis, operation time, external blood loss, complication, pathologic findings, uterine mass, and recovery time of gastrointestinal function.

In all our patients, we used general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. Foley catheter was placed in the bladder and the patients were set at the lithotomy position. The method of MAVH comprises two phases; the transabdominal phase and the transvaginal phase. The pelvic cavity was accessed by the traditional laparotomy with a suprapubic minilaparotomical incision that is 2-2.5 cm long and parallel to the pubic hair line. Through this incision site, the adnexa on both sides of the uterus and other pelvic organs around the bladder were brought into sight by manipulating the uterine elevator that had been already inserted into the uterine cavity through the vaginal canal. By this method, the round ligament, uteroovarian ligament, and the Fallopian tube were exposed at the incision site, clamped with an Allice, and sutured in the figure-of-eight shape. At an interval, the proximal site of the uterine wall was also clamped and sutured in the figure-of-eight shape by the same method. Then, the site between the ligated regions was cut to separate the round ligament, uteroovarian ligament, and the Fallopian tube from the uterus. These organs on the other side were treated in the same way.

When the ovary and the adnexa also had to be removed, the round ligament, the infundibulopelvic ligament, the parovarium, and the Fallopian tube were clamped, sutured, ligated, and cut.

The dissection of the bladder peritoneum was performed as follows; the uterine elevator was elevated and bent backwards to expose the bladder peritoneum; then, it was held by an Allice and infiltrated with normal saline solution or with dilute epinephrine solution which leads to easy separation of the bladder peritoneum from the cervical wall; infiltration was done by 20 gauge spinal needle inserted transabdominally; and the extension and dissection of it was followed by the transvaginal approach. First, the uterine elevator was removed and the mucosal layer around the vaginal cervix was dissected by the circumferential incision of the uterine cervix. The partially attached bladder was completely dissected from the cervix, and access to the pelvic cavity was gained by dissecting the anterior and posterior vaginal fornix.

Afterwards, the uterosacral ligament, the cardinal ligament, and the uterine vessels were clamped, ligated, and cut to completely separate the uterus and the adnexa from the pelvic wall. Then they were removed through the vaginal canal. Ordinarily, the vaginal approach is easier and safer for the uterine artery ligation.

When the size of the uterus to be removed was large, morcellation of the uterus through vaginal canal or the extraperitoneal abdominal uterine morcellation was performed. Although the morcellations were performed mostly through the vagina, the median episiotomy was performed in some cases to enlarge the vaginal canal and to obtain a wider sight. When the extreme size of a uterus made the vaginal hysterectomy impossible, the extraperitoneal abdominal uterine morcellation was performed. The final steps of the operation involved reconfirmation of the complete hemostasis, the suture of the vaginal stump, and the suture of the suprapubic incision.

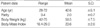

The MAVH was successful in 73 cases (97.3%) out of 75 attempts. In the 2 unsuccessful cases, severe pelvic adhesion was seen through the incision site. Since MAVH was impossible for these 2 cases, we performed abdominal hysterectomy for them. The mean age, parity, weight, and body mass index of the subjects of the 73 cases were 42.6±5.1 yr, 2.0±0.7, 59.5±7.5 kg, and 23.6±2.6, respectively (Table 1). Forty patients (54.8%) had a past history of surgery: 2 patients had 3 previous surgeries, 11 patients had 2 previous surgeries, and 27 patients with 1 surgery, which counts to a total of 55 previous surgeries. The most frequent type of surgery was Caesarean section; 6 patients had a Caesarean section and 8 had repeat cesarean sections, which makes 22 (40%) in total. Other types included 15 tubal ligation (27.2%), 12 adnexectomy (21.8%), and 6 appendectomy (11.0%) (Table 2).

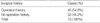

The operational indications were 44 cases (60.3%) of uterine myoma, 19 cases (26.0%) of abnormal uterine bleeding, 7 cases (9.6%) of dysmenorrhea, and 3 other causes (4.1%) (Table 3).

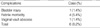

There were 6 cases (8.2%) of cumulative complication; 1 case (1.4%) of bladder injury during the bladder dissection, 1 case of vaginal vault abscess, and 4 cases (5.5%) of febrile morbidity (Table 4). In terms of pathologic diagnosis, there were 54 cases (74.0%) of uterine myoma with adenomyosis, 12 cases (16.4%) of adenomyosis, 2 cases (2.7%) of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer, 2 cases (2.7%) of endometrial polyp, and 3 other cases (4.2%) (Table 5). The uterine mass ranged from 75 g to 1,150 g with an average of 286.8 (±217.5) g. Out of 73 uteri one (1.4%) was measured at less than 80 g, 17 (23.3%) were 81-150 g, 29 (39.7%) were 281-500 g, and 9 (12.3%) were over 500 g. The biggest one was measured at 1,150 g. Morcellation was performed for all uteri measured heavier than 280 g. The extraperitoneal abdominal uterine morcellation was performed in 9 cases where the uterus was heavier than 500 g including the biggest one (Table 6).

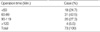

The average operation time for MAVH from skin incision to the completion of suture was 75.8 (±21.8) min. The average bowel function recovery time was 45.9 (±12.9) hr. The external blood loss was 337.0 (±306.8) mL. Eight cases out of 73 required transfusion with an average amount of 1.5 pints (Table 7-1, Table 7-2).

Three decades ago Philip Thorek (13) emphasized the importance of a large incision to secure a good sight for operation, saying "The bigger the surgeon, the bigger the incision. The smaller the surgeon, the smaller the incision."

Such a tradition still seems to hold true for hysterectomy, one of the most frequent operations in the field of gynecology. According to a report (1) in the U.S.A., 64.5% of hysterectomy operations are done transabdominally and the remaining 35.5% transvaginally. The percentage of transabdominal hysterectomy is as high as 93% in Finland (14), 74% in the U.K. (15), and 54% even in the Netherlands that has been famous for a high ratio of vaginal hysterectomy (10). In Australia, the percentage of abdominal hysterectomy decreased from 78% to 57% between 1990 and 1995 due to the increase of laparoscopic hysterectomy (16).

The transabdominal method has many drawlacks compared to the transvaginal method, in terms of pain, scar, morbidity, complication, recovery time, and length of hospitalization. Thus, the latter method has been reported to be more desirable when both methods are possible.

In this context, many minilaparotomical operation methods have been developed. Among them, the laparoscopic operation method has many strong points (17, 18). However, the method also has many weaknesses, such as complicated procedures, longer operation time than in the abdominal approach, high cost, and many contraindications, which lead to its limited application (19). Therefore, development of a simpler method has been suggested.

So the authors have developed a new method of hysterectomy and named it minilaparotomically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (MAVH).

The key point of the MAVH is the suprapubic minilaparotomical incision with the aid of an uterine elevator inserted through the vaginal canal, which makes it possible to bring the uterus and adnexa to the minilaparotomical incision site in association with the evaluation of the pelvic cavity with a dimensional assessment of tissues while watching with eyes, and to facilitate performing bleeding control, clamping, suture, ligation, and dissection of the lesion by a commonly used surgical technique.

Since the minilaparotomy was first introduced by Uchida in 1961 (20), Saunders and Munsick (21) developed a method using a suprapubic minilaparotomy. And Vitoon (22) performed 100 cases of tubal ligation through a minilaparotomical incision of 2.5-3.0 cm parallel to the suprapubic hair line under local anesthesia.

The traditional laparotomical incision inevitably involves separation of the rectus muscle and the sheath leading to the damage of the dermatome of the 12th thoracic nerve that controls the lower abdomen, the ilio-inguinal nerve of the 1st lumbar nerve, and the genitofemoral branch of the 2nd lumbar nerve (23, 24). However, the method of minilaparotomical incision minimizes the damage to those nerves, resulting in less pain and paresthesia after operation. The damage is even less with a horizontal incision.

In terms of the size of incisions, Benadikar (25) performed pelvic surgery with a 1.5-2 inch (3.8-5.1 cm) incision, Hasson et al. (26) performed TAH with a 3-5 cm one, and Johnson (27) performed myomectomy with a 2 cm incision. Bai et al. (22) not only performed tubal ligation but also oophorectomy under general anesthesia through a suprapubic minilaparotomic incision of 2-2.5 cm and by using a uterine elevator. One of the authors of this study, Choi et al. (28) reported a method of tubal ligation through a 2-2.5 cm incision using a uterine elevator under local anesthesia, and have recently performed operations on ovarian cysts and ectopic pregnancy through a suprapubic minilaparotomical incision of 2-2.5 cm using a uterine elevator under general anesthesia.

The uterine elevator inserted into the uterine cavity through the vaginal canal facilitates lifting, extension, flexion, rotation, and lateral movement without damage or perforation of the uterus, which makes it possible to bring and expose the uterus and the adnexa through the incision site for necessary operation. There are many different types of uterine elevators such as Schroder, Vitoon, Semm canula, and Bai type. In this study, a Bai type elevator was used.

The merit of MAVH is that it provides the surgeon with a high visibility even with a minimal incision, which is backed up by the flexibility of the uterine elevator. With the high visibility, actions of operation such as dissection, clamping, ligation, bleeding control, and division can be done perfectly and completely. This effect leads to the decrease in tissue damage, blood loss, and operation time. Minilaparotomy may be a valid alternative to laparoscopy to patients who cannot tolerate abdominal distension. It has all the advantages of a minimally invasive procedure with the availability of tactile feedback and a three dimensional view which the laparoscopic minimal invasive procedure lacks. Moreover, the method is easily reproducible and does not require intense training or expensive equipment; and also it is free from the worries of LAVH such as the damage of blood vessels and intestines by Trochar, accidents by gas, and burns.

The ages of the subjects of this study ranged from 28 to 72 with an average of 42.6 yr, which is comparable to other reports: 41.9 yr for 3,408 cases of VTH (29), 43.1 yr for TAH, 42.6 yr for LAVH, and 40.6 yr for VTH by Kovac (3).

The parity ranged from 0 to 4 (average 2.0). In terms of parity, 1 subject (1.4%) was nulli-parous, and 16 (21.9%) had Caesarean sections. Although these 18 subjects (24.7%) had no experience of vaginal delivery, the MAVH was possible. This fact breaks the prejudice and contraindication against VTH, proving the applicability of the MAVH for women with a history of caesarean section, and also for those nulligravida and nulliparity.

The body weight of the subjects ranged from 42 to 75 kg (average: 59.5 kg), and the body mass index ranged from 18.4 to 29.0 (average: 23.6), which is similar to other reports: 23.1 for 71 cases of LH, and 23.8 for 72 cases of TAH by Olsson et al. (30), and 25.7 for 40 cases of LAVH, and 24.9 for 40 cases of TAH by Kankipati et al. (31) Although obese patients are reported to have high morbidity due to excessive tissue damage, bleeding, and infection, 9 subjects (12.3%) of this study having a BMI over 25 had no problems with the MAVH. This fact eliminates the concerns about performing the MAVH for obese patients.

Among the 73 subjects, 40 had a past history of surgery (Table 2-2). The fact that those 40 (54.8%) subjects had no problems with the MAVH disproves the previous opinion (32) that having a past history of operation is a contraindication against VTH, but supports the opinion of Coulam and Pratt (33) who reported that a past history of operation is not a contraindication against VTH.

In terms of operational indications, 60.3% (44/73) were uterine myoma, followed by 26.0% (19/73) of abnormal uterine bleeding, 9.6% (7/73) of dysmenorrhea, and 4.1% (3/73) of the others. This is largely similar to the previous report by Summitt et al. (6) with their series of 66.7% of uterine myoma, 11.1% of abnormal uterine bleeding, 11.1% of chronic pelvic pain, 3.7% of endometrial hyperplasia, and others (7.4%), showing uterine myoma was the major indication, and was followed by bleeding and pain.

In this study, 6 cases (8.2%) developed surgical complications (Table 4). The ratio of complications is similar to those in other reports of 7.0% by Kovac (3), and 15.8% by Dicker et al. (4). The case complicated by bladder perforation had a past history of repeated Caesarean sections. The bladder perforation was sutured as soon as the leakage of urine was detected, and the patient was discharged in 7 days. The case of vaginal vault abscess readmitted in 2 weeks of fever, diarrhea, and foul odored discharge, which was completely cured after pus drainage. The febrile complications were improved with self-limited conservative treatment.

In the term of pathological diagnosis, myoma with adenomyosis accounted for 74.0% (54/73). In this study the percentage of uterine myoma with adenomyosis was somewhat high. However, the result was basically similar to those in other reports of which the diagnoses were uterine myoma in 23%, endometriosis in 19%, adenomyosis in 16%, adhesive disease in 11%, benign ovarian cyst in 4%, endometrioma in 4%, endometrial adenomatous hyperplasia in 2%, endometrial polyp in 1%, CIN in 1%, others in 1% (34).

The average uterine mass of this study was 286 g. This is somewhat larger than 149 g for 71 cases of LH, 159 g for 72 cases of TAH by Kankipati et al. (32), and 248 g for 77 cases of LH by Robertson and de Blok (10). In this study, the MAVH was successful for the 26 cases (35.6%) with a uterine mass greater than 280 g, which is the size limit according to the instruction given by ACOG (8). Our result indicates that the size of uterus is not a contraindication against MAVH. For the removal of uterus, morcellations were performed for those heavier than 280 g, which is almost the same size of a uterus of 12 weeks pregnancy. For those heavier than 500 g, the extraperitoneal abdominal morcellations were performed because the uterine fundus of these large uteri protruded in the abdominal cavity.

The operation time ranged from 35 to 142 min: 24.7% (18/73) of the patients needed shorter than 60 min; 42.5% (31/73) between 60 and 90 min; 27.3% (20/73) between 90 and 120 min; 5.5% (4/73) over 120 min (Table 7). The average was 75.8 min, which is similar to 93.1 min for 72 cases of TAH by Ellstrom (35), but significantly shorter than that of the endoscope-dependent operation methods. Hidlebaugh and O'Mara (36) spent an average of 139 min for 34 cases of LAVH, and Robertson et al. (10) spent 134 min for 77 cases of LH.

The blood loss ranged from 150 mL to 2,500 mL with an average of 337.0 (±306.8) mL. In 8 cases (11.0%), transfusion was necessary. The range of the amount of blood transfused was 2-8 pints with an average of 1.5 (±2.2) pints.

Five out of the 8 subjects had rather large uteri weighing 825 g, 825 g, 600 g, 320 g, and 280 g, respectively; and they were among the first 20 subjects enrolled for this new operational method. This result illustrates that when the surgeon is less adept and the uterus is too big, severe bleeding can result due to incomplete clamping of uterine vessels.

The bowel function recovery time ranged from 21 to 72 hr with an average of 45.9 (±12.9) hr. This result is similar to 43 hr for 40 cases of VTH, but faster than 54 hr for 40 cases of TAH by Kim et al. (37). For comparison, it took an average of 2.3 days when incisions were smaller than 6 cm, and 2.96 days when incisions were larger than 6 cm (38). A possible explanation would be that fast resumption of the gastrointestinal function is due to less compression, less trauma to the bowel, and no use of abdominal packing gauges. In this study, we did not evaluate the pain and the amount of analgesic needed but nearly all of the subjects of this study were able to move and walk within 24 hr, and were usually hospitalized for 5-7 days for postoperative observations and follow-up. However, a significant number were discharged in 72 hr on requests by patients. This proves that the recovery after MAVH is fast enough.

The above results indicate that MAVH causes relatively minor complications and less bleeding with smaller incisions, less pain, leading to faster recovery, and a small wound, which will be important when cosmetic concerns are high. It is also free from the possible accidents of LAVH; damage of blood vessels or intestines by trochar, accidents by gas, or burns. In addition to all these advantages, the method of MAVH is simple and easy to learn, requiring just a short-term practice and no expensive equipment. Therefore, MAVH is considered as a safe and effective operational method that could replace the abdominal hysterectomy in most cases.

Figures and Tables

References

1. National Hospital Discharge Survey, CD-ROM. 1997. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics.

2. Tobre H. A renaissance for vaginal hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1997. 164:85–87.

4. Dicker RC, Greenspan JR, Strauss LT, Cowart MR, Scally MJ, Peterson HB, De Stefano F, Rubin GL, Ory HW. Complications of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy among women of reproductive age in the United States: The Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982. 144:841–848.

5. Robert FP. Changing indication for vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980. 136:155–160.

6. Summitt RL Jr, Stovall TG, Lipscomb GH, Ling FW. Randomized comparison of laparoscopy-assisted vaginal hysterectomy with standard vaginal hysterectomy in an out patient setting. Obstet Gynecol. 1992. 80:895–901.

7. Wennberg JE. On patient need, equity, supplier-induced demand and the need to assess the outcome of common medical practices. Med Care. 1985. 23:512–520.

8. Precis IV. An update in obstetrics and gynecology. CD-ROM. 1989. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetrians and Gynecologists.

9. Kovac SR, Christie SJ, Bindbeutel GA. Abdominal versus vaginal hysterectomy: a statistical model for determining physician decision making and patient outcome. Med Decis Making. 1991. 11:19–28.

10. Robertson EA, de Blok S. Decrease in number of abdominal hysterectomies after introduction of laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000. 7:523–525.

11. Nezhat C, Bess O, Admon D, Nezhat CH, Nezhat F. Hospital cost comparison between abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopyassisted vaginal hysterectomies. Obstet Gynecol. 1994. 83:713–716.

12. Richardson RE, Bournas N, Magos AL. Is laparoscopic hysterectomy a waste of time? Lancet. 1995. 345:36–41.

13. Philip T. Atlas of surgical techniques. Openings of the abdomen. 1970. J.B Lippincott Company;4–9.

14. Harkki-Siren P, Sjoberg J, Tiitinen A. Urinary tract injuries after hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 92:113–118.

15. Hall V, Overton C, Hargraves J, Maresh M.J.A. Hysterectomy in the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 105:60.

16. Wood C, Maher P, Hill D. The declining place of abdominal hysterectomy in Australia. Gynecol Endosc. 1997. 6:257–260.

17. Boike GM, Elfstrand EP, Delpriore G, Schumock D, Holley S, Lurain JR, John R. Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy in university hospital: Report of 82 cases and comparison with abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993. 168:1690–1697.

18. Nezhat C, Gordon SF, Wilkins E. Laparoscopic versus abdominal hysterectomy. J Reprod Med. 1992. 37:274–250.

19. Mirhashemi R, Harlow BL, Ginsburg ES, Signorello LB, Berkowitz R, Feldman S. Predicting risk of complications with gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 92:327–331.

20. Uchida H. Uchida's abdominal sterilization technique: Proceeding of the third World Congress. Obstet Gynecol. 1961. 1:26.

21. Saunders WG, Munsick RA. Nonpuerperal female sterilization. Simplified, inexpensive technique for partial salpingectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1972. 40:443–446.

22. Bai BJ. Tubal sterilization via suprapubic small incision using newly designed uterine elevator. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1975. 18:307–320.

23. Thompson JD, Rock JA. Operative Gynecology. Incisions for gynecologi surgery. 1997. Lippincott Raven;285–319.

24. Carmine D. Clements. Anatomy of the human body. 1985. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger;1191–1282.

25. Benadikar V. Modified hysterectomy or LAVH, Which is preferable? J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001. 8:S4.

26. Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, Asakura H. Experience with laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1993. 1:1–11.

27. Johnson N. Simplifying laparoscopic surgery for ectopic pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993. 100:286–287.

28. Choi YD, Park KH, Lee SH. Clinical study on abdominal tubal sterilization. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1982. 25:1179–1185.

29. Hoffman MS, De Cesare S, Kalter C. Abdominal hysterectomy versus transvaginal morcellation for the removal of enlarged uteri. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994. 171:309–315.

30. Olsson JH, Ellström M, Hahlim M. A randomized prospective trial comparing laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996. 103:345–350.

31. Raju KS, Auld BJ. A randomized prospective study of laparoscopic vaginal hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy each with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994. 101:1068–1071.

32. Gray LA. Vaginal hysterectomy: indications, technique and complications. 1963. 2nd ed. Spring field: Illinois: Charles G Thomas publisher;71–72.

33. Coulam CB, Pratt JH. Vaginal hysterectomy: Is previous pelvic operation a contraindication? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973. 116:252–260.

34. Ou CS, Beadle E, Presthus J, Smith M. A multicenter review of 839 laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomies. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1994. 1:417–422.

35. Ellström M, Ferraz-Nunes J, Hahlin M, Olosson JH. A randomized trial with a cost-consequence analysis after laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 91:30–34.

36. Hidlebaugh D, O'Mara P, Conboy E. Clinical and financial analyses of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1994. 1:357–361.

37. Kim SW, Chung KM, Chung JH. A study for comparison of vaginal hysterectomy with abdominal hysterectomy. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1990. 33:1549–1561.

38. Son HW, Kim SW, Yoon JH, Jeong MY, Jo HH, Ryu SW, Lee HJ, Kim JH. Influence of minilaparotomy total hysterectomy on clinical course of patients. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 44:1464–1468.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download