Abstract

To evaluate the frequency of bone marrow involvement by nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma, we retrospectively studied biopsy specimens from 40 patients by EBV in situ hybridization (ISH). Three patients had marrow involvement at initial diagnosis (7.5%). In one patient (1/40, 2.5%), the disease in bone marrow was recognized by routine morphological assessment, while two other patients had minimal involvement of lymphoma cells which was recognized only by EBV in situ hybridization (2/40, 5%). Two patients had a disseminated disease at diagnosis and died 6 days and 214 days after diagnosis. One patient had diffuse colonic lesion and died 82 days later. In conclusion, marrow involvement in nasal NK/T cell lymphoma is infrequent at initial diagnosis, and EBV ISH is a useful technique for identifying the minor subgroup of patients which have easily overlooked neoplastic involvement.

NK cell neoplasm is divided into nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma and aggressive NK cell leukemia (1). In contrast to aggressive NK cell leukemia, nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma is localized disease, and bone marrow involvement is uncommon (2-4). Because tumor cells of NK/T cell lymphoma are variable in their morphology and sometimes small and monotonous (5), morphologic identification of neoplastic cells in the bone marrow may be difficult unless the involvement is extensive. As the patients with nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma undergo aggressive clinical course even in patients with low stage disease (3, 4), one may wonder as to whether staging of NK/T cell lymphoma is accurate and minimal bone marrow involvement by nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma can be excluded by routine histologic examination with certainty. EBV in situ hybridization (ISH) is a powerful technique in detecting Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. Because most tumor cells in nasal-type NK/T cell lymphomas are infected by EBV (6-11), we retrospectively performed EBV ISH on bone marrow biopsy specimens from 40 patients to identify minimal infiltration of EBV-infected neoplastic cells and evaluate the frequency of bone marrow involvement by nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma.

During the period from January 1996 to May 2002, 40 patients were diagnosed to have extranodal NK/T cell lymphomas, nasal-type at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. Their clinical and laboratory records were reviewed. All patients had undergone bone marrow biopsy for lymphoma staging at the time of diagnosis.

In all cases, hematoxylin eosin-stained bone marrow biopsies, and aspiration smears were reviewed.

The bone marrow biopsy sections were stained with polyclonal antibody for CD3 (1:200, Novocastra, U.K.), monoclonal antibody for CD20 (1:500, Novocastra, U.K.), and monoclonal antibody for CD56 (1:20, Monosan, Uden, The Netherlands).

Paraffin-embedded sections of the biopsy specimens were deparaffinized with xylene, followed by the treatment with proteinase K, and finally hybridized with fluorescein isothiocynanate-conjugated EBV oligonucleotides (Novocastra, U.K.) complementary to nuclear RNA protein of the EBER1 and EBER2 genes (4). Positive labeling was identified only when cells showed nuclear staining with EBV oligonucleotide. As negative controls, we used EBV negative lymphoid tissues and the hybridization mixture without the EBV oligonucleotides.

The clinicopathologic data of 40 cases are summarized in Table 1.

The series included 28 men and 12 women, with ages ranging from 26 to 81 yr (mean, 45.8 yr). The primary sites of the disease were the nasal cavity in the majority of the patients (27/40, 67.5%), pharynx and larynx in 3, skin in 4, colon in 3, oral cavity in 2 and tongue in one.

The blood cell counts were normal at diagnosis in 20 patients but mild anemia was seen in 14 patients, and leukocytosis or leukocytopenia in 3 patients. Three patients had pancytopenia at diagnosis, and they underwent aggressive clinical course. Unfortunately, they died within 6 months despite chemotherapy or radiation therapy. One patient had concurrent prostatic cancer and NK/T cell lymphoma. Another patient developed cholangiocarcinoma after the diagnosis of NK/T cell lymphoma.

On routine staging, most patients had stage I disease (25/40, 65%), 7 had stage II, 1 stage III, and 5 stage IV at diagnosis. Staging was not available in two patients.

Seventeen patients were treated with combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone (CHOP) regimen. Twenty patients were treated with chemotherapy alone, and 2 of them also received autologous peripheral stem cell transplantation. Two patients were treated with surgery followed by chemotherapy due to intestinal perforation.

Out of 40 patients, follow-up information was available in 37 patients. Twenty-two out of 37 patients (59.5%) died of the disease 6 to 796 days later (mean, 200.9 days; median, 154.5 days). Eight out of 23 patients with stage I disease (34%) died of the disease 25 to 542 days later (mean, 201 days; median, 125.5 days). All 7 patients with stage II disease (100%) died 47 days to 383 days later (mean, 150.7 days; median, 144 days). The patient with stage III died 796 days later and all 5 patients with stage IV, 6 days to 270 days later (mean, 163.6 days; median, 194 days). One patient whose stage was not known died of the disease 143 days later.

Among the bone marrow biopsy specimens obtained from the patients for initial diagnosis, only 3 (7.5%) showed evidence of involvement by NK/T cell lymphoma. In one patient, the neoplastic involvement was recognized by hematoxylineosin stain and immunohistochemistry for pCD3 as well as EBV ISH (1/40, 2.5%) (Fig. 1). The patient had a disseminated disease involving the eye, liver, pancreas, and abdominal lymph node, and died 6 days after the diagnosis. In the other two patients, the disease in the bone marrow was not suspected by routine hematoxylin-eosin stain and immunohistochemistry for pCD3, but recognized by EBV ISH (2/40, 5%) (Fig. 2). One of the last two patients showed disseminated disease involving the liver, spleen, and nasopharynx, and died 214 days after diagnosis. The other had diffuse lesions confined to the colon and pursued aggressive clinical course with colonic perforation but died 82 days after diagnosis.

The frequency of marrow involvement in non-Hodgkin's lymphomas at diagnosis is highly variable, ranging from as low as 3% in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma to as high as 73% in B-cell small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia and lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma (12). It is generally higher in small cell lymphomas and follicular lymphomas. The reported frequency of marrow involvement by NK/T cell lymphoma is known to be low, and is based on morphologic examination in most studies (4, 10). However, morphologically normal marrow may harbor occult lymphoma cells as revealed only by more sensitive techniques for immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor gene rearrangements (13, 14). For example, in the study by Fraga et al. (14), only 17% of the patients with anaplastic large cell lymphoma had marrow involvement by conventional morphologic criteria, while immunostaining for CD30 or epithelial membrane antigen showed occult malignant cells in 23% of patients with negative marrow on histologic examination. Likewise, the morphologic identification of neoplastic involvement of marrow by nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma is difficult unless the involvement is extensive. Isolated tumor cells can be easily overlooked, especially because the neoplastic cells are often small to medium-sized.

In NK/T cell lymphoma, CD56 is a sensitive marker expressed in the majority of the cases. However it is of no use in detecting tumor cells in the bone marrow biopsy specimens, because decalcification process with acid destroys CD56 antigen on the cell surface. EBV ISH is a sensitive technique because normal marrow rarely contains EBV-positive cells (2, 15). In the present study, we determined the frequency of lymphoma involvement of the marrow by nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma with the use of EBV ISH. The results confirm that marrow involvement by nasal type NK/T cell lymphoma is uncommon at diagnosis and EBV in situ hybridization is a useful tool in detecting minimal infiltration of EBV infected tumor cells.

Two patients with bone marrow involvement had disseminated disease proven by clinical and radiologic studies at diagnosis, which suggests that bone marrow involvement in nasaltype NK/T cell lymphoma is a late event in the course of disease. Another patient with bone marrow involvement had a colonic disease and was initially diagnosed as stage I by Ann Arbor Staging System (16). It is noteworthy that the lesion in the colon involved the entire colonic segments diffusely, which indicates higher tumor burden than expected in the estimated stage.

Ann Arbor Staging System is based on nodal lymphomas such as Hodgkin's lymphoma and B-cell lymphoma. In contrast to extranodal B-cell lymphoma which usually forms a single mass, multifocal or diffuse ulcerative involvement of one or two anatomical segments of the intestine is a common finding in NK or T cell lymphoma (17). In Ann-Arbor Staging System, diffuseness or multifocality of the lesion in NK or T-cell lymphoma are not taken into account, which can lead to underestimation of the tumor stage.

It is difficult to establish the definite prognostic significance of marrow involvement in nasal type NK/T cell lymphoma because of the aggressive nature of the disease with very short survival time in the majority of patients and the small number of cases with marrow involvement. In this study, all three patients with bone marrow involvement died of the disease.

In conclusion, minimal involvement of bone marrow is infrequent in nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma. And EBER ISH is a useful technique for identifying minimal involvement of bone marrow by nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma, which is easily overlooked but closely related with poor prognosis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Case 2 showing bone marrow involvement by NK/T cell lymphoma, which is identified by HE stain (A) as well as by EBV in-situ hybridization (B).

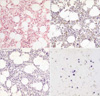

Fig. 2

Case No. 20. NK/T cell lymphoma in bone marrow is not suspected by H&E stain (A) and immunohistochemical stain with CD 3 (B) and CD56 (C), but detected by EBER in-situ hybridization (D).

References

1. Tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 2001. Lyon, France: IARC Press.

2. Wong KF, Chan JK, Cheung MM, So JC. Bone marrow involvement by nasal NK cell lymphoma at diagnosis is uncommon. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001. 115:266–270.

3. Cheung MM, Chan JKC, Lau WH, Foo W, Chan PT, Ng CS, Ngan RK. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the nose and nasopharynx: clinical features, tumor immunophenotype, and treatment outcome in 113 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998. 16:70–77.

4. Kwong YL, Chan AC, Liang R, Chiang AK, Chim CS, Chan TK, Todd D, Ho FC. CD56+ NK lymphomas: clinicopathological features and prognosis. Br J Haematol. 1997. 97:821–829.

5. Chinen K, Kaneko Y, Izumo T, Ohkura Y, Matsubara O, Tsuchiya E. Nasal natural killer cell/T-cell lymphoma showing cellular morphology mimicking normal lymphocytes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002. 126:602–605.

6. Chan JK, Yip TT, Tsang WY, Ng CS, Lau WH, Poon YF, Wong CC, Ma VW. Detection of Epstein-Barr viral RNA in malignant lymphoma of the upper aerodigestive tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994. 18:938–946.

7. Quintanilla-Martinez L, Franklin JL, Guerrero I, Krenacs L, Naresh KN, Rama-Rao C, Bhatia K, Raffeld M, Magrath IT. Histological and immunophenotypic profile of nasal NK/T cell lymphomas from Peru: high prevalence of p53 overexpression. Hum Pathol. 1999. 30:849–855.

8. Van Gorp J, Weiping L, Jacobse K, Liu YH, Li FY, De Weger RA, Li G. Epstein-Barr virus in nasal T-cell lymphomas (polymorphic reticulosis/midline malignant reticulosis) in western China. J Pathol. 1994. 173:81–87.

9. Tao Q, Ho FC, Loke SL, Srivastava G. Epstein-Barr virus is localized in the tumour cells of nasal lymphoma of NK, T or B cell type. Int J Cancer. 1995. 60:315–320.

10. Sin LLP, Chan JKC, Kwong YL. Natural killer cell malignancies: clinicopathologic and molecular features. Histol Histopathol. 2002. 17:539–554.

11. Ko YH, Ree HJ, Kim WS, Choi WH, Moon WS, Kim SW. Clinicopathologic and genotypic study of extranodal nasal-type natural killer/T-cell lymphoma and natural killer precursor lymphoma among Koreans. Cancer. 2000. 15:2106–2116.

12. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group Classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 1997. 89:3909–3918.

13. Gaulard P, Kanavaros P, Farcet JP, Rocha FD, Haioun C, Divine M, Reyes F, Zafrani ES. Bone marrow histologic and immunohistochemical findings in peripheral T cell lymphoma: a study of 38 cases. Hum Pathol. 1991. 22:331–338.

14. Fraga M, Brousset P, Schlaifer D, Payen C, Robert A, Rubie H, Huguet-Rigal F, Delsol G. Bone marrow involvement in anaplastic large cell lymphoma: immunohistochemical detection of minimal disease and its progonostic significance. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995. 103:82–89.

15. Wong KF, Chan JK, Lo ES, Wong CS. A study of the possible etiologic association of Epstein-Barr virus with reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in Hong Kong Chinese. Hum Pathol. 1996. 27:1239–1242.

16. Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, Smithers DW, Tubiana M. Report of the committee on Hodgkin's disease staging classification. Cancer Res. 1971. 31:1860–1861.

17. Choe WH, Kim YH, Kim BJ, Lee JU, Lee JH, Son HJ, Rhee PL, Kim JJ, Paik SW, Rhee JC, Ko YH, Lee WY, Chun HK. The different colonoscopic manifestations of primary colorectal lymphomas by their cellular origin. Intestinal Res. 2003. 1:22–30. (in Korean).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download