Abstract

Peripheral neuropathies occur in lymphoma patients. Causes of neuropathy include chemotherapy, opportunistic infections, and the lymphoma itself. We report a patient with lymphoma whose chief complaint was a sensory loss in the hands and feet. Electrophysiologic studies and sural nerve biopsy showed sensory polyneuropathies. We hypothesize that this neuropathy is associated with lymphoma-related ganglionopathy, and among the possible causes, we suspect that a systemic cause such as a paraneoplastic syndrome is the most likely pathogenic etiology. However, further follow-up will be necessary to see whether sensory symptoms change with lymphoma treatment.

Peripheral neuropathy is one of the rare complications of lymphoma. The most common causes of lymphoma-related neuropathy are local infiltration of lymphoma and proliferation of the lymphoma inside of peripheral nerve tissue (1). Other causes of lymphoma-related neuropathy are loss of dorsal root ganglion cells, (2) the neurotoxic effects of drugs such as vincristine, (3) and viral infections such as HIV (4). However, paraneoplastic syndrome is a rare cause of lymphoma-related neuropathy (3). We report a case of peripheral sensory loss, which may be due to a lymphoma-induced paraneoplastic syndrome.

The thirty-four year old male was presented to the hospital with tingling or burning sensations in both hands and feet that began 20 months ago. The symptom first started from his feet. Recently, the burning had progressed to his hands. There was no past history of alcoholism or any long-term medication use.

On neurological examination, all the cranial nerve functions, including pupillary light reflexes, were normal. Motor strength of the upper and lower limbs was grade V by the NMC classification. Both hands and feet had severe loss of vibration and position sensation compared to the chin and slight loss of pain and thermal sensation compared to the face.

Deep tendon reflexes of bilateral upper and lower limbs were reduced and there was no Babinski sign. Tinnel's sign was negative in bilateral wrists and ankles. There was no abnormal sweating in the face and trunk, and changing body position did not affect blood pressure significantly.

On admission, there were two palpable masses found in the left inguinal area, but the patient could not clarify when they first appeared. The masses were measured 2 cm and 4 cm in diameter, and were partially movable and non-tender. Just after the admission, his blood laboratory values were: WBC 22,500/µL, RBC 5.27×106/µL, hemoglobin 15.8 g/dL and platelets 329,000/µL. His WBC differential counts were: segmented neutrophils 84% and lymphocytes 12%. Electrolytes and liver function tests were normal. Hemoglobin A1c was 5.7%, and CRP was increased to 2.13 mg/dL. In his cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), WBC count was 6/mL, and 92% of them were lymphocytes. CSF protein was 42.3 g/dL and glucose was 53 mg/mL. CSF cytology was negative for malignant cells. Other tests, specifically cryoglobulins, antinuclear antibody, and anti-Sm antibody, anti-SS-A, anti-SS-B antibody, and ANCA were all negative. In addition, antibodies to HIV were negative by ELISA. Several tests to rule out other acquired polyneuropathies were performed and all results were normal: TSH 4.7 µU/mL, free T4 0.87 ng/dL, vitamin B12 311 pg/mL, folate 1.1 ng/mL.

Bone marrow biopsy was negative for neoplastic lymphoid cell infiltration. No monoclonal immunoglobulins were found on immunofixation electrophoresis of serum and urine. Indirect immunofluorescent stain of triple tissue slides (stomach, cerebellum, kidney) showed no known paraneoplastic antibodies, including anti-Hu, anti-Ri, anti-Yo, and antiamphiphysin antibodies.

Electrophysiological studies showed that the action potentials of sensory nerve in all limbs were not detectable but the parameters for motor nerves, including F-waves, were within normal limits (Table 1). On plain chest radiograph and chest CT scan, there were no pathological findings suggesting metastases. However, on abdominal CT scan, multiple lymphadenopathy was found in the left inguinal canal, para-aortic space, and pelvic cavity.

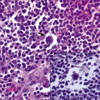

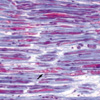

After the admission, biopsies of the left inguinal mass and the left sural nerve were performed. Grossly, the inguinal mass measured 8.5 cm in its greatest dimension, and it was well-encapsulated, grayish tan, and solid with fresh fish appearance. Microscopically, the mass exhibited diffuse effacement of lymph node architecture and multiple granulomas (Fig. 1). Many large atypical mononuclear or binuclear cells, including Reed-Sternberg cells, were scattered among many mature lymphocytes rare eosinophils, and plasma cells (Fig. 2). By immunohistochemical staining, the large atypical cells were tested positive for CD15 and CD30, and the diagnosis of Hodgkin's disease lymphocyte rich (classical) type, was made from the inguinal mass (5).

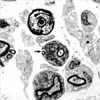

The sural nerve biopsy showed several myelin digestion chambers, suggesting axonal degeneration on modified Gomori stain (Fig. 3). There was no evidence of vasculitis or inflammatory neuropathy. There was no neoplastic lymphoid cell infiltration of the sural nerve. On electron microscopy, the sural nerve showed the loss of small and large myelinated fibers with axonal sprouting and myelin ovoids, suggesting an axonal neuropathy (Fig. 4).

Patient was diagnosed with stage IIB Hodgkin's lymphoma and discharged after one cycle of chemotherapy with adriamycin and bleomycin.

This patient had clinical symptoms suggestive of a sensory polyneuropathy, and electrophysiological and pathological studies confirming this diagnosis. We sought for the mechanisms that could link lymphoma to peripheral neuropathy in this case because we could find no other obvious cause for the sensory loss of the patient.

The incidence of peripheral neuropathy is approximately 1-2% in patients with lymphoma (6). However, Walsh et al. reported that 35% of lymphoma patients have electrophysiological evidence of neuropathy regardless of their symptoms (7).

Previous reports in the Korean literatures have described the lymphoma patients with the associated peripheral neuropathies (8, 9). However, the mechanism in this previous report was direct infiltration of the nerves by the lymphoma (9). In contrast, in the current case there was no evidence of direct tumor infiltration.

There are several reports that tried to relate lymphoma and neuropathy. Schold et al. observed neuronal degeneration in anterior horn cells and posterior spinal columns and segmental demyelination of spinal roots and brachial and lumbar plexi from the autopsy of the patients suffered with lymphoma (10). They suggested that these autopsy findings are due to radiation therapy and opportunistic viral infection. Thomas et al. reported the infiltration of lymphocytes in the epineurium of sural nerve from a lymphoproliferative disorder patient (11). They suggested the possibility that this finding is due to a systemic effect of circulating monoclonal immunoglobulins. Plante-Bordeneuve et al. proposed sensory neuropathies associated with lymphoma correspond to a variant of Hodgkin's disease-associated inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy rather than to a true paraneoplastic sensory ganglionitis (12). However, Lee et al. reported the case of a patient with CNS lymphoma, who had severe peripheral polyneuropathy (13). This patient had an IgM kappa monoclonal paraproteinemia, and his symptoms improved with the treatment of the lymphoma and the decreased paraprotein levels, suggesting a monoclonal immunoglobulin as a possible cause of his neuropathy.

In this case, we suspected systemic causes rather than the local infiltration of lymphoma cells or compression by tumor mass as an explanation for the sensory loss because the patient had symmetric pure sensory polyneuropathy. Cryoglobulinemia and paraneoplastic antibody-mediated nerve damage are likely systemic pathogenic mechanisms of polyneuropathy (14). Despite negative findings on paraneoplastic antibody and paraprotein tests in this patient, we could not rule out the possibility of a systemic cause because there may be other paraproteins that cannot be measured by standard serum electrophoresis, and there may be other paraneoplastic antibodies that we could not measure.

In this case, we suspect that an antibody against some antigen expressed by primary sensory neurons may induce axonal degeneration after passing through weak points in the blood brain barrier near spinal nerve roots or dorsal root ganglia. In this case, evoked sensory nerve action potentials are diffusely absent. These findings support the possibility of ganglionopathies. And the reason this patient had sensory deficits rather than motor deficits is that this antibody chiefly affected dorsal root ganglion neurons. However, the ganglionopathy of paraneoplastic syndrome may rarely occur after lymphocyte infiltration of the dorsal root ganglia (15).

So, further evaluation will be necessary to clarify the pathogenic causes of this case by following up whether his symptoms change as lymphoma treatment progress.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Lymph node biopsy (H&E stain, ×20). Microscopically, the mass exhibits diffuse effacement of lymph node architecture and granulomas. Inset is the enlarged picture (×200) of the area indicated by arrow. |

| Fig. 2Lymph node biopsy (H&E stain, ×200). Reed-Sternberg cells (solid arrow) are scattered among a background of many mature lympocytes. Arrow inside inset shows mitosis. |

| Fig. 3Sural nerve biopsy (modified Gomori trichrome stain, ×100). The sural nerve biopsy shows several myelin digestion chambers (arrow), suggesting axonal degeneration. |

| Fig. 4Sural nerve biopsy (EM findings, ×7,000). The sural nerve shows loss of small and large myelinated fibers and degenerating axons with myelin ovoids (arrow), suggesting axonal neuropathy. |

References

1. Vital C, Vital A, Julien J, Rivel J, deMascarel A, Vergier B, Henry P, Barat M, Reiffer J, Broustet A. Peripheral neuropathies and lymphoma without monoclonal gammopathy: A new classification. J Neurol. 1990. 237:177–185.

2. Sterman AB, Schaumburg HH, Asbury AK. The acute sensory neuronopathy syndrome: a distinct clinical entity. Ann Neurol. 1980. 7:354–358.

3. Dumitru D, Amato AA, Zawarts MJ. Electrodiagnostic medicine. 2002. 2nd. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus;992–993.

4. Gherardi RK, Chretien F, Delfau-Larue MH, Authier FJ, Moulignier A, Roulland-Dussoix D, Belec L. Neuropathy in diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome. An HIV neuropathy, not a lymphoma. Neurology. 1998. 50:1041–1044.

5. Chen YT, Godwin TA, Mouradian JA. Immunohistochemistry and gene rearrangement studies in the diagnosis of malignant lymphomas: A comparison of 152 cases. Hum Pathol. 1991. 22:1249–1257.

6. McLeod JG. Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Griffin JW, editors. Peripheral neuropathy associated with lymphomas, leukemias, and polycythemia vera. Peripheral neuropathy. 1993. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders;1591–1598.

8. Kim HW, Park SY. A case of angiocentric T cell lymphoma accompanied with multiple erythematous nodules, subcutaneous mass on the right face and peripheral polyneuropathy. Korean J Hematol. 1997. 32:140–145.

9. Kim CH, Paik KW. A case report of infiltrative polyneuropathy associated with lymphoma. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2001. 25:724–728.

10. Schold SC, Cho ES, Somasundaram M, Posner JB. Subacute motor neuronopathy: A remote effect of lymphoma. Ann Neurol. 1979. 5:271–287.

11. Thomas FP, Vallejos U, Foitl DR, Miller JR, Barrett R, Fetell MR, Knowles DM, Latov N, Hays AP. B cell small lymphocytic lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia with peripheral neuropathy: two cases with neuropathological findings and lymphocyte marker analysis. Acta Neuropathol. 1990. 80:198–203.

12. Plante-Bordeneuve V, Baudrimont M, Gorin NC, Gherardi RK. Subacute sensory neuropathy associated with Hodgkin's disease. J Neurol Sci. 1994. 121:155–158.

13. Lee SM, Harper P, Luthert P, Hughes RAC. Primary CNS lymphoma in association with IgM kappa paraproteinaemia and peripheral polyneuropathy: A case report. Eur Neurol. 1995. 35:237–239.

14. Gemignani F, Marchesi G, Di Giovanni G, Salih S, Quaini F, Nobile-Orazio E. Low-grade non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma presenting as sensory neuropathy. Eur Neurol. 1996. 36:138–141.

15. McLeod JG. Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Griffin JW, editors. Paraneoplastic neuropathies. Peripheral neuropathy. 1993. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders;1583–1590.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download