Abstract

Ventricular septal defect (VSD) can be associated with various complications such as aortic regurgitation (AR). AR in VSD come from a deficiency or hypoplasia of the conal septum which leads to abnormal apposition in diastole and prolapse of the poorly supported noncoronary or right coronary cusp through the VSD into the right ventricle resembling subpulmonic stenosis and subsequently results in distortion of the aortic valve and progressive AR. AR often increases in severity with age and it indicates a worse prognosis. Therefore, appropriate timing of surgical repair in progressive AR in VSD might be important. Until now, many earlier experiences about surgical repair of AR complicating VSD were on adolescents or young adults. We reported a case of AR in 48-year-old male patient with right coronary cusp prolapse complicating the subarterial type of VSD which was properly assessed by echocardiography and was successfully treated with surgical repair. Right coronary cusp or noncoronary cusp prolapse should be suspected in AR complicating VSD through proper echocardiographic assessment and the surgical repair on VSD and distorted aortic valve should be considered in the old patient, as well as the young.

Ventricular septal defect (VSD) accounts for 20% of the congenital cardiovascular malformations and 10% of those VSDs diagnosed in adults. The vast majority of VSDs (roughly 70%) are located in the area of the membranous septum and they are defined as being perimembranous or subarterial. With a relative high incidence in Asian countries,1) the association of the subarterial type VSD with aortic valve prolapse (AVP), and mainly right coronary cusp prolapse, and aortic regurgitation (AR) has been shown. According to the previous reports, the incidence of AVP in the subarterial VSD was 36% to 79%.2)3) The peak age for AVP is around 7 years, and that for AR is between 5 and 10 years.3)4) VSD is a very common congenital heart defect in children, but due to spontaneous and surgical closure, it is less commonly encountered in adults.

When VSD is found in adult, about one-third of patents with VSD initially managed medically required surgical intervention later in life.5-7) In a tertiary referral population, there was an report that 25% of patients with small VSDs had serious complications, such as AR and endocarditis; these were the most common indications for surgical VSD closure in adults.6) Many experiences published case reports about surgical repair of AR complicating VSD in adolescents or young adults patients.5-7) But old adult patient was little known.

Here we reported a case of AR in a patient with right coronary cusp prolapse that was complicating a subarterial type VSD and the patient was 48 years old. It was diagnosed by thorough echocardiographic assessment and the patient underwent successful surgical closure of the VSD along with aortic valvuloplasty.

A 48-year-old male visited emergency department due to retrosternal chest pain at rest for 6 hours and dyspnea on exertion for 3 months. He had been diagnosed with hypertension a year previously, but he had not taken any medication. He was a current smoker with 30 pack-years history and he drank alcohol daily. However, he had no medical history of arrhythmias, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease or stroke. On arrival in the emergency department, his blood pressure was 150/90 mm Hg, his pulse rate was 100 bpm, his respiratory rate was 18 breaths per minute and his body temperature was 36.5℃. Cardiac auscultation revealed regular heart sounds with a pansystolic murmur and the lung sounds were clear. The initial electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm and the chest radiography demonstrated a normal sized heart. The laboratory studies were within the normal limits.

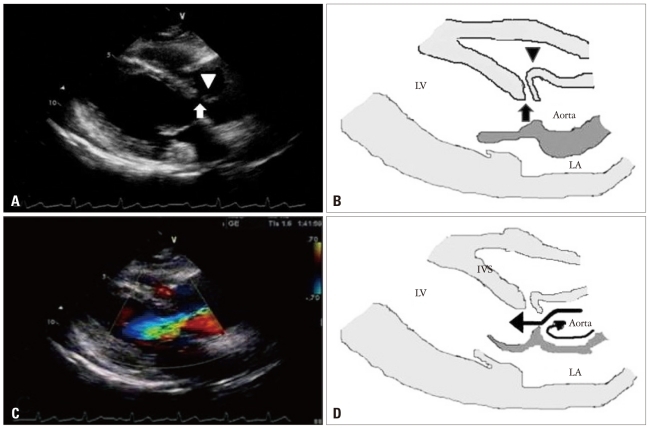

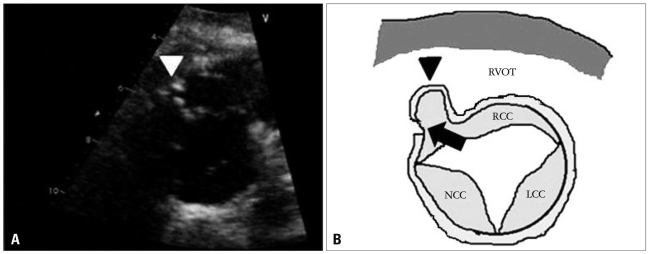

The initial transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed mild right ventricular outflow obstruction resembling subpul monic stenosis (Fig. 1), a subarterial type VSD of 4.2 mm diameter with left to right shunt flow (Qp/Qs = 2.01) and pressure gradient corresponding to 136 mm Hg. The right ventricular systolic pressure was 69 mm Hg and right ventricle was mildly hypertrophic. In parasternal long-axis view of TTE, the high velocity jet produced by the left-to-right shunt, through the VSD, results in a Venturi effect, displacing the unsupported annulus outward into the right ventricle (Fig. 2A and B). There was severe AR (Fig. 2C and D) with subtle right coronary cusp prolapse which caused mild right ventricular outflow obstruction. Also, in parasternal short-axis view at aortic level of TTE, there was right ventricular outflow tract obstruction due to right coronary cusp (RCC) driven into the right ventricle by high velocity left-to-right shunt flow (Fig. 3A and B).

Cardiac catheterization revealed that Qp/Qs and mean pulmonary artery pressure were measured as 1.41 and 19 mm Hg, respectively. Coronary angiography showed no significant luminal narrowing in coronary arteries.

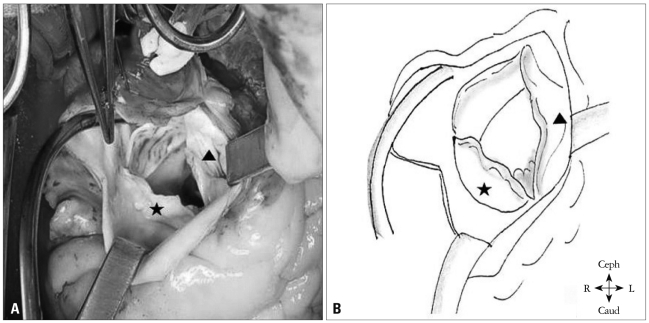

Although the Qp/Qs was low, we decided to perform an operation because he had dyspnea and severe AR. The surgical findings showed a prolapsed and retracted RCC and commissural calcification between the RCC and the noncoronary cusp (NCC). The VSD was nearly closed by the RCC (Fig. 4). He underwent surgical VSD closure with autopericardium through a pulmonary arteriotomy, and RCC mobilization with decalcification and commissurotomy between the RCC and the NCC. The post-operative course was uneventful. Post-operative TTE was performed and this revealed no residual shunt and only mild AR. In follow-up (after 48 months) examination, he had no symptom, and there was no specific change in follow-up TTE.

In this report, we present a case of complicated VSD with severe AR due to right coronary cusp prolapse resembling subpulmonic stenosis in the relatively old adult. Although the patient's complicated VSD was diagnosed later in life, he was successfully treated with surgical repair after thorough echocardiographic assessment.

Echocardiography is the noninvasive method of choice for evaluating a VSD. It is a sensitive, descriptive tool with an excellent detection rate (88% to 95%), depending on the size and location of the defect and the technician's experience.8)9)

Thorough echocardiographic examination is best achieved by imaging the interventricular septum in multiple planes using color flow and spectral Doppler echocardiography. Echocardiography is most sensitive for defects larger than 5 mm and that are located in the membranous, inlet or outlet portion of the septum. It is least sensitive for detecting apical muscular defects. Echocardiography can confidently identify the morphologic features of the defect, including its size and borders and any associated defects.10)11) It also provides accurate hemodynamic assessment of the shunt and its severity, the volume overload, a subpulmonic (double-chambered right ventricle) or pulmonic stenosis, and pulmonary hypertension.12) In addition, echocardiography can assess the degree of aortic valve distortion and prolapse (the right and noncoronary cusps) in patients with a subarterial VSD and it can evaluate the severity of AR and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction caused by the prolapsing coronary cusp.13) Yearly echocardiographic assessment of AR has important prognostic implications, and especially with regard to the timing of surgical treatment. The mechanism of AVP in patients with subarterial VSD may include a lack of infundibular septal support, intrinsic discontinuity of the aortic valve annulus and aortic media, and a Venturi effect of the VSD jet.4)

The risk for AVP and regurgitation in patients with membranous or subarterial defects increases with age.14)15) AR is believed to be 2.5 times more frequent in patients with subarterial VSDs. Momma et al.15) reported on 395 patients with subarterial defects: AR was seen in 50% of the patients by 8 years and in 87% of the patients by 20 years. As the AVP progresses, the intraventricular shunting decreases at the expense of aortic valve distortion and regurgitation. This increases the risk for endocarditis, left ventricular volume overload, and less commonly, right ventricular outflow tract obstruction and sinus of Valsalva aneurysm.16)17) The progressive nature of the AR and the associated increased morbidity have led to recommending early surgical intervention.18)19) However, unless endocarditis supervenes, the rate of progression is often slow and variable. Therefore, the proper timing and type of operation are still controversial. The treatment of an isolated VSD depends on the type of defect, its size, the shunt's severity, the pulmonary vascular resistance, the functional capacity and the associated acquired anomalies, such as AR, subpulmonic stenosis, or pulmonary hypertension.20)21) Surgical closure of a VSD in adult decreases the risk for endocarditis by at least 50%, it reduces the pulmonary artery pressure, it improves the functional classification.21)22) and it can be accomplished with very low short- and long-term mortality and morbidity.23)

The case gives us two important lessons. The first, RCC or NCC prolapse should be suspected in AR complicating VSD through proper echocardiographic assessment. The second lesson was surgical repair of complicated VSD provides good result to the old adult patient, as well as the young.

References

1. Ammash NM, Warnes CA. Ventricular septal defects in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2001; 135:812–824. PMID: 11694106.

2. Soto B, Becker AE, Moulaert AJ, Lie JT, Anderson RH. Classification of ventricular septal defects. Br Heart J. 1980; 43:332–343. PMID: 7437181.

3. Ueda M, Fujimoto T, Becker AE. The infundibular septum in normal hearts and in hearts with isolated ventricular septal defect. A comparison between Japanese and Dutch hearts. Jpn Heart J. 1986; 27:635–643. PMID: 3820574.

4. Elgamal MA, Hakimi M, Lyons JM, Walters HL 3rd. Risk factors for failure of aortic valvuloplasty in aortic insufficiency with ventricular septal defect. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999; 68:1350–1355. PMID: 10543505.

5. Kidd L, Driscoll DJ, Gersony WM, Hayes CJ, Keane JF, O'Fallon WM, Pieroni DR, Wolfe RR, Weidman WH. Second natural history study of congenital heart defects. Results of treatment of patients with ventricular septal defects. Circulation. 1993; 87:I38–I51. PMID: 8425321.

6. Neumayer U, Stone S, Somerville J. Small ventricular septal defects in adults. Eur Heart J. 1998; 19:1573–1582. PMID: 9820997.

7. Gabriel HM, Heger M, Innerhofer P, Zehetgruber M, Mundigler G, Wimmer M, Maurer G, Baumgartner H. Long-term outcome of patients with ventricular septal defect considered not to require surgical closure during childhood. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002; 39:1066–1071. PMID: 11897452.

8. Lue HC, Sung TC, Hou SH, Wu MH, Cheng SJ, Chu SH, Hung CR. Ventricular septal defect in Chinese with aortic valve prolapse and aortic regurgitation. Heart Vessels. 1986; 2:111–116. PMID: 3759798.

9. Mori K, Matsuoka S, Tatara K, Hayabuchi Y, Nii M, Kuroda Y. Echocardiographic evaluation of the development of aortic valve prolapse in supracristal ventricular septal defect. Eur J Pediatr. 1995; 154:176–181. PMID: 7758512.

10. Sohn DW. Symptom based echocardiographic approach: dyspnea. J Korean Soc Echocardiogr. 2004; 12:5–9.

11. Pieroni DR, Nishimura RA, Bierman FZ, Colan SD, Kaufman S, Sanders SP, Seward JB, Tajik AJ, Wiggins JW, Zahka KG. Second natural history study of congenital heart defects. Ventricular septal defect: echocardiography. Circulation. 1993; 87:I80–I88. PMID: 8425326.

12. Garg A, Shrivastava S, Radhakrishnan S, Dev V, Saxena A. Doppler assessment of interventricular pressure gradient across isolated ventricular septal defect. Clin Cardiol. 1990; 13:717–721. PMID: 2257713.

13. Schmidt KG, Cassidy SC, Silverman NH, Stanger P. Doubly committed subarterial ventricular septal defects: echocardiographic features and surgical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988; 12:1538–1546. PMID: 3057035.

14. Backer CL, Idriss FS, Zales VR, Ilbawi MN, DeLeon SY, Muster AJ, Mavroudis C. Surgical management of the conal (supracristal) ventricular septal defect. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991; 102:288–295. discussion 295-6. PMID: 1865702.

15. Momma K, Toyama K, Takao A, Ando M, Nakazawa M, Hirosawa K, Imai Y. Natural history of subarterial infundibular ventricular septal defect. Am Heart J. 1984; 108:1312–1317. PMID: 6496290.

16. Mahoney LT. Acyanotic congenital heart disease. Atrial and ventricular septal defects, atrioventricular canal, patent ductus arteriosus, pulmonic stenosis. Cardiol Clin. 1993; 11:603–616. PMID: 8252562.

17. Menahem S, Johns JA, del Torso S, Goh TH, Venables AW. Evaluation of aortic valve prolapse in ventricular septal defect. Br Heart J. 1986; 56:242–249. PMID: 3756041.

18. Leung MP, Beerman LB, Siewers RD, Bahnson HT, Zuberbuhler JR. Long-term follow-up after aortic valvuloplasty and defect closure in ventricular septal defect with aortic regurgitation. Am J Cardiol. 1987; 60:890–894. PMID: 3661405.

19. Otterstad JE, Erikssen J, Frøysaker T, Simonsen S. Long term results after operative treatment of isolated ventricular septal defect in adolescents and adults. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1986; 708:1–39. PMID: 3461690.

20. Ellis JH 4th, Moodie DS, Sterba R, Gill CC. Ventricular septal defect in the adult: natural and unnatural history. Am Heart J. 1987; 114:115–120. PMID: 3604855.

21. Gersony WM, Hayes CJ, Driscoll DJ, Keane JF, Kidd L, O'Fallon WM, Pieroni DR, Wolfe RR, Weidman WH. Second natural history study of congenital heart defects. Quality of life of patients with aortic stenosis, pulmonary stenosis, or ventricular septal defect. Circulation. 1993; 87:I52–I65. PMID: 8425323.

22. Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, del Nido P, Fasules JW, Graham TP Jr, Hijazi ZM, Hunt SA, King ME, Landzberg MJ, Miner PD, Radford MJ, Walsh EP, Webb GD, Smith SC Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW. American College of Cardiology. American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines on the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease). American Society of Echocardiography. Heart Rhythm Society. International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease. Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Society of Thoracic Surgeons. ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines on the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease). Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 52:e1–e121. PMID: 19038677.

23. Mongeon FP, Burkhart HM, Ammash NM, Dearani JA, Li Z, Warnes CA, Connolly HM. Indications and outcomes of surgical closure of ventricular septal defect in adults. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010; 3:290–297. PMID: 20298987.

Fig. 1

Transthoracic echocardiography with the short-axis view at the aortic level (A) with continuous wave Doppler at the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) (B). It showed mild RVOT obstruction resembling subpulmonic stenosis (arrowhead) with increased peak and mean pressure gradients (32 mm Hg and 19 mm Hg, respectively).

Fig. 2

The transthoracic parasternal long axis views on admission with illustrations. A and B: There were a discontinuity on interventricular septum showing subarterial type ventricular septal defect (VSD, arrow) and a finger-like projection of sinus of Valsalva (arrowhead) resulting from longstanding high velocity jet through VSD. C: Severe aortic regurgitant jet was identified with color Doppler. D: A section of the aortic root illustration showed the direction of blood flow (arrows). LV: left ventricle, LA: left atrium, IVS: interventricular septum.

Fig. 3

The transthoracic short-axis view at the aortic level on admission (A) and illustration (B). The right coronary cusp and sinus of Valsalva are driven into the right ventricle (RV) due to longstanding high velocity jet produced by the left-to-right shunt (arrow). As the result, the right ventricular outflow tract obstruction occurred (arrowhead). RCC: right coronary cusp, NCC: noncoronary cusp, LCC: left coronary cusp, RVOT: right ventricular outflow tract.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download