Abstract

Endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation may be associated with variant angina (VA). The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the level of von Willebrand factor (VWF) and flow-mediated dilation (FMD) are related to VA. This study included 74 patients (VA group: 52.1±11.9 years, 40 males) with normal coronary angiogram (CAG) and positive ergonovine provocation test (ERT), and 33 patients (control group:49.7±10.8 years, 23 males) and normal CAG with negative ERT. The level of VWF was significantly higher in VA than in control group (163.0±43.4% vs. 127.2±59.6%, p=0.008). FMD was significantly decreased in VA group compared with control group (9.0±4.0% vs. 1.2±3.1%, p=0.008). The levels of white blood cell counts was higher in VA than in control group (7509.4±2411.1/mm3 vs. 6303.1±2027.1/mm3, p=0.015). The level of total cholesterol was significantly higher in VA group compared with the control group (185.2±45.3 mg/dL vs.166.2±36.9 mg/dL, p=0.042). In multiple regression analysis, the VWF [odds ratio (OR), 11.14, 95% confidence interval (CI), 3.25-38.15: p<0.001) and FMD (OR, 4.42, 95% CI, 1.32-14.82: p=0.016)] were predictors of VA. On the basis of the receiver-operating characteristics analysis, the cutoff value of VWF >140% and FMD <10% provided the best separation of patients with and without VA (sensitivity 0.73, 0.66; specificity 0.78, 0.69, respectively). The increased level of VWF and decreased FMD are independently associated with VA. Non-invasive evaluation of VWF and FMD may serve as useful markers for detecting endothelial dysfunction and screening the VA patients.

The prevalence of variant angina (VA) is apparently higher in Korean and Japanesepat-ients than in Caucasian counterparts.1-4 Endothelial ysfunction is involved in every stage of the progression of atherosclerosis 5,6 and is non-invasively measured by flowmediated dilation (FMD) of the brachial artery.7

Besides these traditional risk factors, several other risk factors and surrogate markers for the early detection of atherosclerosis including the measurement of endothelial dysfunction, and serologic markers of vascular inflammation have recently been proposed and widely studied.8 Several studies have suggested that a variety of factors may contribute to endothelial dysfunction in patients with VA.9-11 These include impaired flow-dependent coronary dilation due to decreased activity of the vasodilator nitric oxide,12,13 which in some patients may be the result of mutation in the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene. Also, inflammation may play a role since patients with VA have elevated serum C-reactive protein concentrations, as reported in one series, were found to be elevated lying between controls and patients with acute coronary syndrome.14 In addition, there are structural endothelial abnormalities in the arteries that manifest spasm. Intravascular ultrasound examination has shown that, patients with vasospasm have diffuse intimal thickening in the coronary arteries that develop spasm, which is independent of other traditional risk factors for coronary artery disease.15 These changes may be due in part to local vascular injury induced by vasospasm itself.16

There are few reports about VA risks. Particularly, those in VA patients treated with conventional cardiovascular disease risk management in the Asian population still remain to be clarified. Loss of adequate endothelial cell function is most widely quantified by assessing FMD or measuring plasma markers such as von Willebrand factor (VWF). However, no studies have demonstrated a relationship between the levels of VWF and FMD versus VA. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate whether the level of VWF and FMD are related to VA in Korean patients.

From March 12, 2005 to November 9, 2007, a total 107 subjects (63 men and 44 women) with suspected VA were analyzed. FMD, VWF, inflammatory and coagulation marker were measured early in the morning following overnight fasting for more than 12 hours. We studied 74 Korean VA patients (group I: 52.1±11.9 years: 40 men, 34 women) who fulfilled the following criteria: (1) presence of spontaneous chest pain associated with ST segment elevation on resting 12-lead electrocardiogram or ambulatory electrocardiogram, (2) a positive result on ergonovine-provocation testing, and (3) the absence of significant organic coronary stenosis (>50%) based on coronary angiography. We also studied 33 patients with negative result on ergonovineprovocation testing and no evidence of significant coronary stenosis (group II: 49.7±10.8 years: 23 men, 10 women).

FMD of brachial artery as the non-invasive parameter of endothelial function was measured according to the guideline described previously.7 Vasoactive therapies were not prescribed for at least 24 hours before the study until the measurement was completed except for only short-acting sublingual nitroglycerin (NTG), which was withheld 1 hour before the study.

All studies were performed early in the morning (6:00~8:00 hours) before coronary angiography, using a 8-MHz high resolution lineal vascular ultrasound transducer (Acuson 512, USA) employed to image the brachial artery longitudinally just above the antecubital fossa. The tourniquet measuring blood pressure was placed on the lower arm in order to create shear stress induced by reactive hyperemia.

After baseline measurements of the brachial artery diameter, the blood pressure cuff was inflated to at least 50 mmHg above systolic blood pressure to occlude arterial flow for 5 minutes. Subsequent deflation of the cuff induced a brief high flow state through the brachial artery (reactive hyperemia) to accommodate the dilated resistance vessels. The resulting increase in shear stress caused the brachial artery to dilate. The brachial artery was continuously imaged for the first 2 minutes of reactive hyperemia. The flow-mediated dilatory response was used as a measure of endothelium-dependent dilation. After the 10-min rest to reestablish baseline condition, 0.6 mg of NTG was administered sublingually.

The brachial artery was continuously imaged for 5 minutes to measure peak diameter. The dilatory response to NTG was used as a measure of endotheliumindependent dilation. Patients with menstruation cycle were excluded from the study, because the varying levels of estrogen may affect endothelial function. In our studies, the intra- and inter-observer variability for the repeated measurements of resting arterial diameter was very satisfactoy (r=0.997, p<0.001, r=0.997, p< 0.001).

Transthoracic m-mode, two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography examinations were performed in all patients. The echocardiographic parameters were measured on the parasternal long and on the apical four chamber views.

All anti-anginal regimen was not prescribed for at least 24 hours before catheterization, except for the unrestricted use of sublingual nitroglycerin (NTG). Diagnostic coronary angiography was performed via right femoral approach with the use of a 5- or 6-F catheter. After baseline coronary angiograms were done, incremental doses of ergonovine maleate were infused into the left coronary artery (5µg/min, 10µg/min and 30 µg/min) for 3 minutes with 2 minutes intervals between consecutive doses. When coronary spasm was induced, NTG (200µg) was given as an intra-coronary injection. A positive ergonovine-provocation test was defined as >50% focal reduction in the diameter of the artery during coronary angiography associated with ST segment changes and/or typical chest pain after intracoronary injection of the drugs.

We measured the blood levels of VWF for examining endothelial function, white blood cell (WBC) counts, high-sensitively C-reactive protein (hs-CPR), homocystein for examining the inflammatory activity, and fibrinogen for the coagulation system. Blood samples were taken by venipuncture in the morning after fasting for over 12 hours before angiography. VWF was measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique using commercial reagents (R& D systems, USA) and hs-CRP was measured by immunoturbidimetric CRP- Latex (II) assay using Olympus AU 5400. Measurements of fibrinogen was performed by chromogenic assay (Sysmex, CA1500, USA).

All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS (version 15.0). Results were expressed as number (%) or the mean±SD. Comparisons between groups were performed using Student's t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of VA. Receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) analysis was used for determining optimal cutoff value defined as the point with the highest sum of sensitivity and specificity. The area under the ROC curve was used to quantify the ability to predict VA.

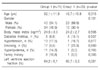

The clinical characteristics including the risk factors of the study population are summarized in Table 1. There was a male predominance in Group I and II. However, there was no significant difference.

Comparison of the biochemical markers is summarized in Table 2. The levels of hs-CRP, fibrinogen, homocysteine were not different between the two groups. However, the levels of WBC counts and of total cholesterol were significantly elevated in Group I than in Group II. To be of note, however, was the level of VWF significantly elevated in Group I compared with Group II.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to determine independent predictors of VA. All variables with p<0.05 in univariate analysis were tested. The independent predictive factors of VA are shown in Table 4. VWF and FMD were independent predictors of VA (odds ratio, 11.14, 95% confidence interval, 3.25~38.15, p<0.001; and odds ratio, 4.42, 95% confidence interval, 1.32~14.82, p=0.016, respectively). The most powerful predictor for predicting VA was VWF. On the basis of the ROC analysis, the cut off value of VWF >140% (sensitivity 0.73, specificity 0.78) and FMD <10% provided the best separation of patients with and without VA (sensitivity 0.66, specificity 0.69, respectively) (Fig 2).

In the present study, significantly impaired brachial artery FMD and significantly increased level of VWF were observed in VA patients compared with agematched control subjects. Our study demonstrated that the increased level of VWF and decreased FMD can serve as useful markers for detecting endothelial dysfunction and for screening the VA patients. This study has clearly shown the importance of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in the development of coronary diseases in Korean patients with VA.

The vascular endothelium has been reported to be a multifunctional organ whose integrity is essential for normal vascular physiology.17,18 Decreased flow-mediated dilation in patients with VA has recently been reported, 11,19 and there is growing evidence that endothelial function abnormalities are present before the development of angiographically evident coronary atherosclerosis in patients with coronary risk factors.20,21

VWF is a multifunctional plasma protein that plays a very important role in hemostasis following vascular injury. As a consequence of vascular injury, the subendothelial matrix and collagen fibers are exposed to the blood flow. Circulating platelets adhere to the injured site and initiate the process of thrombosis. Subendothelial VWF plays an important role in mediating platelet adhesion at the injured site. VWF is secreted from the vascular endothelium in response to vascular injury and disease. Thus, raised plasma levels of VWF were reported to be associated with widespread endothelial damage/dysfunction and atherothrombosis. Recently, VWF is generally accepted and used as a marker for endothelial damage/dysfunction,22,23 and we have reported data regarding the relationship between VA and VWF in Korean patients.24 Episodes of coronary spasm usually occur in a circadian rhythm, with increased prevalence of anginal attacks from midnight to early morning.25 Therefore, we performed the FMD study early in the morning between 6:00 and 8:00 am, expecting that FMD in VA patients may be minimal early in the morning.

The present study shows that an increased level of VWF and decreased FMD could predict VA and also vascular events, which might have implications for the assessment and management of cardiovascular risk in VA patients. Medical interventions including lipidlowering therapy, angiotension-converting enzyme inhibitors, exercise, and smoking cessation are known to reduce cardiovascular disease risk and also improve endothelial function.26

Importantly, the presence of increased level of VWF and endothelial dysfunction in patients with VA suggests that they may be at higher risk for the future development of severe cardiovascular disease. Clearly, these results by no means indicate causality. Better evidence for such a relation would be provided by demonstration that successful treatment of VA is associated with improved endothelial function and decreased inflammatory markers. Presenly, the patients with VA are, in general, being treated with either calcium channel blocker or nitrates,27 but sometimes these regimen are not enough to treat certain patients with VA. In those cases, demonstration of atherosclerotic change by FMD and VWF level may assist in determining treatment options. Furthermore, VWF and the vascular endothelial function/integrity may present targets for the development of novel anti-inflammatory drugs in VA patients.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample size was relatively modest, so that further studies in larger scale are in need. Secondly, we did not demonstrate the mechanism involved in the increased plasma VWF. Thus, further prospective studies are needed in order to establish true mechanisms of chest pain in patients with increased plasma VWF, to render clues in searching a novel pharmaceutical therapy targeting endothelial dysfunction, and also to investigate the potential role of plasma VWF as an aide to risk stratification in patients with VA.

In conclusion, the increased level of VWF and decreased FMD are independently associated with VA. Non-invasive evaluation of VWF and FMD may serve as useful markers for detecting endothelial dysfunction in the VA patients.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1The flow-mediated dilation (FMD) was significantly decreased in patients with variant angina (Group I) than in control patients (Group II). However, the nitroglycerin-mediated dilation (NMD) was not different between both groups. |

| Fig. 2The receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curve to determine optimal cutoff value of Von Willebrand factor (Left) and flow-mediated dilation (Right) for predictors of patients with variant angina. CI, confidence interval. |

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants of the Korea Health 21 R&D Project Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A050174) and Cardiovascular Research Foundation Asia.

References

1. Kang JA, Lee YS, Jeong SH, Lee JW, Kim BY, Im DS, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with variant angina. Korean J Med. 2002. 63:195–202.

2. Beltrame JF, Sasayama S, Maseri A. Racial heterogeneity in coronary artery vasomo-tor reactiviety: differences between Japanese and Caucasian patients. J Am CollCardiol. 1999. 33:1442–1452.

3. Bertrand ME, LaBlanche JM, Tilmant PY, Thieuleux FA, Delforge MR, Carre AG, et al. Frequency of provoked coronary arterial spasm in 1089 consecutive patients undergoing coronary angiography. Circulation. 1982. 65:1299–1306.

4. Pristipino C, Beltrame JF, Finocchiaro ML, Hattori R, Fujita M, Mongiardo R, et al. Major racial differences in coronary constrictor response between Japanese and Caucasians with recent myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000. 101:1102–1108.

5. Selwyn AP, Kinlay S, Creager M, Libby P, Ganz P. Cell dysfunction in atherosclerosis and the ischemic manifestations of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1997. 79:17–23.

6. Grundy SM, Pasternak R, Greenland P, Smith S Jr, Fuster V. Assessment of cardiovascular risk by use of multiple-risk-factor assessment equations: a statement for health care professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 1999. 100:1481–1492.

7. Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, Celermajer D, Charbonneau F, Creager MA, et al. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial ArteryReactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002. 39:257–265.

8. Patel SN, Rajaram V, Pandya S, Fiedler BM, Bai CJ, Neems R, et al. Emerging, noninvasive surrogate markers of atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2004. 6:60–68.

9. Kugiyama T, Motoyama T, Hirashima O, Ohgushi M, Soejima H, Misumi K, et al. Vitamin C attenuates abnormal vasomotor reactivity in spasm coronary arteries inpatients with coronary spastic angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998. 32:103–109.

10. Motoyama T, Kawano H, Kugiyama K, Okumura K, Ohgushi M, Yoshimura M, et al. Flow-mediated, endothelium-dependent dilation of the brachial arteries is impaired inpatients with coronary spastic angina. Am Heart J. 1997. 133:263–267.

11. Kawano H, Ogawa H. Endothelial function and coronary spastic angina. Internal Med. 2005. 44:91–99.

12. Kugiyama K, Yasue H, Okumura K, Ogawa H, Fujimoto K, Nakao K, et al. Nitric oxide activity is deficient in spasm arteries of patients with coronary spastic angina. Circulation. 1996. 94:266–271.

13. Kugiyama K, Ohgushi M, Motoyama T, Sugiyama S, Ogawa H, Yoshimura M, et al. Nitric oxide-mediated flow-dependent dilation is impaired in coronary arteries inpatients with coronary spastic angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997. 30:920–926.

14. Hung MJ, Cherng WJ, Yang NI, Cheng CW, Li LF. Relation of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level with coronary vasospastic angina pectoris in patients without hemodynamically significant coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005. 96:1484–1490.

15. Miyao Y, Kugiyama K, Kawano H, Motoyama T, Ogawa H, Yoshimura M, et al. Diffuse intimal thickening of coronary arteries in patients with coronary spastic angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000. 36:432–437.

16. Suzuki H, Kawai S, Aizawa T, Kato K, Sunayama S, Okada R, et al. Histologicevalution of coronary plaque in patients with variant angina: relationship betweenvasospasm and neointimal hyperplasia in premary coronary lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999. 33:198–205.

17. Hung MJ, Cherng WJ, Cheng CW, Li LF. Comparison of serum levels of inflammatory markers in patients with coronary vasospasm without significant fixed coronary artery disease versus patients with stable angina pectoris and acute coronary syndromes with significant fixed coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006. 97:1429–1434.

18. Maseri A, Severi S, Nes MD, L'Abbate A, Chierchia S, Marzilli M, et al. "Variant" angina: one aspect of a continuous spectrum of vasospastic myocardial ischemia. Pathologenetic mechanisms, estimated incidence and clinical and coronaryarteriographic findings in 138 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1978. 42:1019–1035.

19. Teragawa H, Kato M, Kurokawa J, Yamagata T, Matsuura H, Chayama K. Endothelial dysfunction in an independent factor responsible for vasospastic angina . Clin Sci (Lond). 2001. 101:707–713.

20. Vita JA, Treasure CB, Nabel EG, McLenachan JM, Fish RD, Yeung AC, et al. Coronary vasomotor response to acetylcholine relates to risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1990. 81:491–497.

21. Saito S, Yamagishi M, Takayama T, Chiku M, Koyama J, Ito K, et al. Plaquemorphology at coronary sites with focal spasm in variant angina: study using intravascular ultrasound. Circ J. 2003. 67:1041–1045.

22. Yazici M, Demircan S, Durna K, Yasar E, Sahin M. Relationship between myocardialinjury and soluble P-selectin in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes. Circ J. 2005. 69:530–505.

23. Tanis B, Algra A, Van der Graaf Y, Helmerhorst F, Rosendaal F. Procoagulationfactors and the risk of myocardial infarction in young women. Eur J Haematol. 2006. 77:67–73.

24. Cho SH, Park IH, Jeong MH, Hwang SH, Yun NS, Hong SN, et al. Increased inflama-tory markers and endothelial dysfunction are associated with variant angina. Korean Circ J. 2007. 37:27–32.

25. Ogawa H, Yashe H, Oshima S, Okumura K, Matsuyama K, Obata K. Circadianvariation of plasma fibrinopeptide. A level in patientss with variant angina. Circulation. 1989. 80:1617–1626.

26. Vita JA, Keaney JF Jr. Exercise-toning up the endothelium? N Engl J Med. 2000. 342:503–505.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download