This article has been corrected. See "Erratum: The Significance and Limitations of Korean Diagnosis-Related Groups in Psychiatric Inpatients' Hospital Charges" in Volume 56 on page 98.

Abstract

Objectives

This study was conducted to investigate whether the charges associated with Korean Diagnosis-Related Groups for mental health inpatients adequately reflect the degree of medical resource consumption for inpatient treatment in the psychiatric ward.

Methods

This study was conducted with psychiatric inpatients data for 2014 from the National Health Insurance claim database. The main diagnoses required for admission, classification of the hospitals, and main treatment services were analyzed by examining descriptive statistics. Homogeneities of the major diagnostic criteria were assessed by calculating coefficient variances. Explanation power was determined by R2 values.

Results

The most frequent disorders for psychiatric inpatient treatment were alcohol-use disorder, depressive episodes, bipolar affective disorder, and dementia in Alzheimer's disease. Hospitalization and psychotherapy fees were the main medical expenses. Regardless of the homogeneity of the disease group, duration of hospital stay was the factor that most influenced medical expenses. In the psychiatric area, explanation power of Korean Diagnosis-Related Groups was 16.52% (p<0.05), which was significantly lower than that for other major diagnostic area.

Conclusion

Most psychiatric illnesses are chronic, and the density of services can vary depending on illness severity or associated complications. The current Korean Diagnosis-Related Groups criteria did not adequately represent the amount of in-hospital medical expenditures. A novel Korean classification system that reflects the expenditures of medical resources in psychiatric hospitals should be developed in order to provide appropriate reimbursements.

Figures and Tables

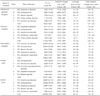

Table 1

Lists of Major Diagnostic Criteria (MDC)-19 and -20 in Korean Diagnostic-Related Groups version 4.0

Table 2

The comparison of hospital charges in admission and mean days-of-stay to the types of hospital

Table 3

The comparison of hospital charges in admission in most frequent five disorders to the types of hospital

References

1. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. 2014 National Health Insurance Statistical Yearbook. Wonju: Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service;2015.

2. Kim JK. Significance of improvement of compensation for payment system and diagnosis-related groups. J Legislative Stud. 2012; 37:241–249.

3. Kim Y. The improvement model for new diagnosis-related groups. Wonju: Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service;2015.

4. Kang KW. Medical service payment system and cost of Health Insurance. In : Shin YS, Kim YI, editors. Health policy and management. Seoul: Seoul National University Press;2013. p. 320–356.

5. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. KDRG version 4.0. Wonju: Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service;2016.

6. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Medical fee index 2015. Wonju: Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service;2015.

7. Stranges E, Levit K, Stocks C, Santora P. State variation in inpatient hospitalizations for mental health and substance abuse conditions, 2002-2008: statistical brief #117. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2011.

8. Garfield RL. Mental health financing in the United States: a primer. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation;2011.

9. Jun J. Current status of mental illness comorbidity and political tasks. Issue Focus. 2014; 241:1–8.

10. Stensland M, Watson PR, Grazier KL. An examination of costs, charges, and payments for inpatient psychiatric treatment in community hospitals. Psychiatr Serv. 2012; 63:666–671.

11. Hewlett E, Moran V. Making mental health count: the social and economic costs of neglecting mental health care. Paris: OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing;2014.

12. Kang GW, Park H, Shin YS. Refinement and evaluation of Korean diagnosis related groups. Korean J Health Policy Adm. 2004; 14:121–147.

13. Averill RF, Muldoon JH, Vertrees JC, Goldfield NI, Mullin RL, Fineran EC, et al. The evolution of casemix measurement using diagnosis related groups (DRGs). Wallingford: 3M HIS Research Report;1998. p. 5–98.

14. Lee DH, Park EC, Nam CM, Lee SG, Lee DH, Yu SH. Comparing difference of volume of psychiatric treatments between the patient with Health Insurance and those with medical assistance: for inpatients of Korean psychiatric hospitals. Korean J Prev Med. 2003; 36:33–38.

15. Nmhc.or.kr [homepage on the Internet]. 2015 national report of mental health. cited 2016 Nov 28. Available from: http://www.nmhc.or.kr.

16. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Mental health and addictions data and information guide. 2014. cited 2016 Nov 28. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/Data_Guide_for_MHA_at_CIHI_2014_ENrev.pdf.

17. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. 2013 report of oversea business trip for patient classification system. cited 2016 Nov 28. Available from: http://xn--1-2x5ez25autobvo.com/cms/open/04/03/11/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2013/10/08/NCCC.pdf.

18. Mhaustralia.org [homepage on the Internet]. Canberra: Constitution of Mental Health Australia Ltd.;cited 2016 Nov 28. Available from: https://mhaustralia.org/tags/amhcc.

19. National Health Service. Mental health clustering booklet. London: National Health Service;2016.

20. Suh SK, Kim Y, Park JI, Lee MS, Jang HS, Lee SY, et al. Medical care utilization status and associated factors with extended hospitalization of psychiatric patients in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2009; 42:416–423.

21. Cha SK, Kim SS. The determinant of the length of stay in hospital for schizophrenic patients: using data from the in-depth injury patient surveillance system. J Digit Converg. 2013; 11:351–359.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download