Abstract

We describe a case of spontaneous bleeding from a branch of the right internal pudendal artery that resulted in massive scrotal swelling in a patient who had underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention with the use of abciximab concurrent with conventional anticoagulation and dual antiplatelet therapies for the treatment of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. This unusual complication was promptly identified by percutaneous peripheral arteriography and successfully treated with gel-foam embolization.

Antithrombotic therapies using anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents play an essential role during percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) for the prevention of thrombotic complications. However, it has been well-documented that use of drugs with more potent antithrombotic effects is associated with an increase in the risk of bleeding. Recently, we experienced a rare case of spontaneous bleeding from a branch of the right internal pudendal artery that resulted in massive scrotal swelling in a patient who had underwent primary PCI with the use of abciximab concurrent with conventional anticoagulation and dual antiplatelet therapies for the treatment of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). This unusual complication was promptly identified by a percutaneous peripheral arteriography and successfully treated with gel-foam embolization.

A 53-year-old man presented to the emergency department of our hospital with severe chest pain. His past medical history was unremarkable except for a history of dyslipidemia. His initial electrocardiogram showed ST-segment elevation in the anterior leads, and management for acute STEMI was initiated. The patient was given acetylsalicylic acid (300 mg), clopidogrel (300 mg) and unfractionated heparin (a 4000 U bolus followed by a 860 U/h infusion) at the emergency department. Bedside transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated hypokinetic anterior and anteroseptal wall motion with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (about 35%). The patient was sent to the cardiac catheterization laboratory for primary PCI.

Emergency coronary angiogram was performed via the right femoral artery, which was successfully cannulated with a single puncture. A 0.035 inch guide wire (InQwire, Merit Medical, South Jordan, UT, USA) was inserted and advanced under fluoroscopic guidance. There was no resistance encountered while inserting and advancing the guide wire. Coronary angiography revealed thrombotic total occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery (pLAD). Percutaneous revascularization of the pLAD was performed using balloon angioplasty (Sprinter Legend, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), followed by deployment of a everolimus-eluting stent (Xience Prime, Abbott Vascular, SantaClara, CA, USA), which led to optimal angiographic results with the restoration of Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarct grade 3 flow. However, repeat coronary angiogram performed shortly after the stent implantation revealed acute in-stent thrombosis. Thus, abciximab was started according to the standard bolus and infusion regimen for the treatment of acute stent thrombosis (0.25 mg/kg intravenous [IV] bolus followed by 0.125 mcg/kg/min continuous IV infusion). Repeat coronary angiogram performed 30 min after the administration of abciximab showed the remaining in-stent thrombus. However, we decided to finish the procedure because the patient was free of chest pain, and coronary angiogram demonstrated patent flow of pLAD without propagation of the thrombus. The activated clotting time (ACT; Hemochron device, International Technidyne Corporation, Edison, NJ, USA) measured at the end of the procedure was 183 seconds. The right femoral artery puncture site was closed with an Angio-seal device (St. Jude Medical, Minetonka, MN, USA). After successful closure of the puncture site, continuous heparin infusion was started at a reduced dose of 6 U/kg/hr at the physician's discretion.

Approximately 1 hour after the procedure, his blood pressure dropped to 80/50 mmHg and his heart rate increased up to 130 beats/min. Upon physical examination, his cardio-respiratory system and abdomen were normal. The femoral puncture site was normal without swelling or discoloration of the skin in the groin area. However, he had massive swelling with discoloration in the scrotal and perineal regions (Fig. 1). Repeat bedside transthoracic echocardiography showed no significant change in left ventricular systolic function compared with prior examination. At this time, the most likely diagnosis was hypovolemic shock due to procedure-related puncture site bleeding, but bleeding from other arteries could not be excluded. There were no abnormal findings in the laboratory examinations on bleeding diathesis performed at the emergency department: complete blood count revealed a platelet count of 220×109/L, and the coagulation profile revealed a prothrombin time international normalized ratio of 0.99 as well as an activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of 33.2 seconds. Prompt fluid resuscitation and packed red blood cells transfusion were initiated, and the abciximab and heparin infusion was stopped. We decided to perform percutaneous peripheral arterial exploration to localize the source of bleeding.

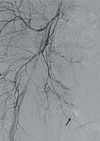

Emergent angiography was undertaken via the left femoral artery. Right femoral arteriogram showed no contrast extravasation. However, right internal iliac arteriogram revealed contrast extravasation from a branch of the right internal pudendal artery (Fig. 2). The bleeding branch was superselected by a microcatheter and gel-foam was deployed. Repeat arteriogram confirmed successful gel-foam embolization by showing the absence of contrast extravasation (Fig. 3). The patient subsequently underwent incision and drainage the next day to remove a large amount of residual blood in the scrotum. The patient remained hemodynamically stable after the procedures, and was discharged 7 days later.

Bleeding complication is more frequent when PCI is performed during acute coronary syndrome compared with elective procedures due to the need for more potent antithrombotic therapies. Abciximab, a potent inhibitor of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, is frequently used in cardiac catheterization laboratories because it has been shown to improve clinical outcomes in patients undergoing PCI, especially in the setting of acute coronary syndrome including STEMI with angiographic evidence of large thrombus or other thrombotic complications.1) However, this agent is well known to be associated with an increase in both minor and major bleeding complications. Such complications are mostly related to bleeding from the arterial puncture sites, and include other types of bleeding such as gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding as well as alveolar hemorrhage.2)3) In addition, spontaneous bleeding from unusual arterial branches unrelated to the access site has been described in several case reports with the use of abciximab.4)5)

Our report is another interesting case of spontaneous bleeding from an unusual arterial branch, which may draw attention to a disastrous complication in association with the administration of abciximab concurrent with conventional anticoagulation and dual antiplatelet therapies. To the best of our knowledge, spontaneous bleeding from a branch of the right internal pudendal artery during abciximab therapy has not been previously reported. This complication was neither puncture site-related bleeding nor spontaneous bleeding from common causative sites. Rather, it presented as scrotal swelling mimicking puncture site bleeding, which could delay the clinical judgement.

This case shows the value of angiographic examination in conjunction with a high degree of suspicion based on the clinical presentation for the localization of the source of bleeding. Furthermore, this case demonstrates the effectiveness of gel-foam embolization for the control of bleeding in this setting without rapid reversal of anticoagulation and antiplatelet activities. Although the infusion of platelet concentrates and/or coagulation factor products might have been helpful for hemostasis, it would have increased the risk of thrombus propagation in the presence of the remaining in-stent thrombus.

In addition, it is worth discussing strategies for minimizing the risk of bleeding associated with abciximab, especially used in conjunction with unfractionated heparin. First, it is recommended to use a weight-adjusted, reduced-dose heparin regimen under ACT guidance during PCI, and to discontinue heparin after PCI. If anticoagulation needs to be continued after PCI, heparin should be used at a reduced-dose with aPTT maintained at lower therapeutic levels.6) Second, careful vascular access site management is important to prevent bleeding. When attempting vascular access, care should be taken to ensure that only the anterior wall of the artery is punctured. Also, unnecessary arterial and venous punctures should be avoided. Third, if performed by an experienced operator, the risk of puncture site-related bleeding may be reduced with a radial approach.7)8) Fourth, some investigators suggested that immediate post-PCI reversal of anticoagulation by protamine was associated with a significant reduction in major bleeding complications among patients undergoing primary stenting with adjunctive abciximab therapy.9)

In conclusion, although rarely reported, spontaneous bleeding from unusual arterial branches in association with the use of abciximab concurrent with conventional anticoagulation and dual antiplatelet therapies during or after PCI can be life-threatening. This unusual complication can be promptly identified by angiographic examination in conjunction with a high degree of suspicion based on the clinical presentation and can be successfully treated with gel-foam embolization without rapid reversal of anticoagulation and/or antiplatelet activities.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Massive swelling with discoloration of scrotal and perineal regions suggesting bleeding complication on physical examination.

References

1. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Stone GW, et al. Abciximab as adjunctive therapy to reperfusion in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA. 2005; 293:1759–1765.

2. Cote AV, Berger PB, Holmes DR Jr, Scott CG, Bell MR. Hemorrhagic and vascular complications after percutaneous coronary intervention with adjunctive abciximab. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001; 76:890–896.

3. Khanlou H, Eiger G, Yazdanfar S. Abciximab and alveolar hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339:1861–1863.

4. Cherukuri M, Pershad A. Late spontaneous epigastric arterial bleeding associated with abciximab: successful percutaneous treatment with coil gel-foam embolization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2002; 14:692–693.

5. Dorval JF, Soulez G, Berry C, Bonan R. Management of a spontaneous renal capsule hematoma following cardiac catheterization involving use of a platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor: a case report. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007; 69:994–997.

6. American College of Emergency Physicians. Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. O'Gara PT, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:e78–e140.

7. Dziewierz A, Rakowski T, Dudek D. Abciximab in the management of acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation: evidence-based treatment, current clinical use, and future perspectives. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014; 10:567–576.

8. Iqbal Z, Cohen M, Pollack C, et al. Safety and efficacy of adjuvant glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors during primary percutaneous coronary intervention performed from the radial approach for acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2013; 111:1727–1733.

9. Parodi G, De Luca G, Moschi G, et al. Safety of immediate reversal of anticoagulation by protamine to reduce bleeding complications after infarct artery stenting for acute myocardial infarction and adjunctive abciximab therapy. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010; 30:446–451.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download