Abstract

Percutaneous device closure of atrial septal defect (ASD) is an alternative treatment to surgery. The main advantages of the percutaneous approach include avoidance of surgery, short procedure time and hospital length, in addition to comparable rates of complications. However, percutaneous device closure is associated with infrequent early and late complications including device embolization, air embolism, cardiac tamponade and thrombotic complications. We report a rare complication of silent and late device embolization of the ASD occluder device into the right pulmonary artery, three months after implantation.

Secundum type atrial septal defect (ASD) is one of the most common congenital heart defects that occur in adults.1) In the past, ASD was closed surgically. Percutaneous device closure of ASD has been developed as an alternative treatment to surgery.2) The first percutaneous device closure of ASD was performed in 1974.3) Percutaneous device closure has several advantages over surgery, including less surgical morbidity, avoidance of a scar and reduced hospitalization duration.4) However, this method of closure is associated with rare early and late complications. We report a rare complication of silent and late device embolization of the ASD occluder device into the right pulmonary artery, three months after implantation.

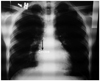

A 16 year-old patient presented with dyspnea. Clinical examination revealed normal vital parameters with a fixed split second heart sound and a 2/6 systolic ejection murmur heard best at the left upper sternal border. The respiratory system examination was unremarkable. His electrocardiography revealed sinus rhythm and there was rsR' in lead V 1. The patient was initially evaluated by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and had a typical ostium secundum type ASD. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) confirmed the presence of a moderately large sized secundum ASD that measured 20 mm. The aortic rim was almost absent (2-3 mm) with other surrounding rims >7 mm (not thin). The length of the interatrial septum was 45 mm in the longitudinal plane and 48 mm in the shortaxis view. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia with TEE guidance. The 30 mm sizing balloon was positioned across the defect and measured by both quantitative angiography and TEE at 21 mm. A 24-mm ASD septal occluder device (Occlutech Figulla ASD Occluder N, International Occlutech AB, Helsingborg, Sweden) was deployed with fluoroscopic and transesophageal echocardiographic guidance. Before releasing the device, fluoroscopy and the "Minnesota tug technique" were also used to confirm its position. Cessation of flow across the interatrial septum was confirmed on TEE prior to final deployment of device. After no shunt was observed, the procedure was terminated. TTE was performed 24 hours, seven days and one month after the implantation and confirmed adequate device position with no significant residual shunting. At the third month physical examination, a fixed split second heart sound and a systolic ejection murmur was heard within the pulmonary area. Chest roentgenogram showed the ASD closure device in the area of the right pulmonary artery (Fig. 1). Echocardiography showed device migration into the right pulmonary artery without any significant obstruction to forward flow into the right pulmonary artery (Fig. 2). The patient was clinically asymptomatic. When the patient was interviewed again, he had complained of mild chest discomfort for a short duration during lifting of a heavy object fifteen days prior to being seen. Right ventriculography and fluoroscopy also showed embolization of the device into the right pulmonary artery (Fig. 3). Percutaneous removal of the device was not considered because of the position of the device in the right pulmonary artery. The patient was referred for surgical retrieval of the device and closure of the defect, and underwent median sternotomy under general anesthesia, while cardiopulmonary bypass was performed by aorta-bicaval cannulation. The aorta was crossclamped. ASD closure device was removed out of the right pulmonary artery through arteriotomy performed on the main pulmonary artery, and secundum type ASD primary closure operation was performed through the right atriotomy. Following surgical retrieval, the device was macroscopically intact (Fig. 4). There were no problems in the postoperative follow-ups; additionally there was no leakage from atrial septum in the follow-up echocardiography.

Surgical closure of an ASD is the gold standard treatment regardless of the size and number of defects present in any clinical case.2)5) Percutaneous transcatheter closure of ASD is an established alternative treatment to surgical closure as it has lesser morbidity, shorter hospital stay, lack of a scar, and comparable rates of complications.4-6) However, percutaneous device closure is associated with rare early and late complications such as migration or embolization of the device, pericardial effusion, arrhythmias, thrombus formation on the device, and mitral regurgitation and vascular injury.4)7)8) The most frequent complication of percutaneous transcatheter closure of ASD is device embolization with incidence ranging from 4% to 21%.9) Embolization usually occurs within 24 hours and after that, it is rarely seen. Factors relating to device embolization are associated with the type of device used, larger size of defect, thin rim of atrial tissue, mobility of device postimplantation, use of undersized device and deficiency or absence of aortic rim.2)4)7)8) The aortic rim is very important and a margin <5 mm may predispose to both early and late device embolization.2) Our patient had a moderately large secundum ASD and very small aortic rim (2-3 mm), the combination of which may have resulted in embolization of the device at a late period.

Another potential cause of late device embolism is acute change in intracardiac pressure due to physical strain. A sudden increase in afterload to the left heart in conjunction with diminished right heart filling (valsalva) may have favored the migration of the device to the right and subsequently to the pulmonary artery.10) Ten weeks after the procedure, when the patient was lifting a heavy object, he had complained of mild chest discomfort for a short duration of time. The history of our patient suggests that an acute change in intracardiac pressure due to physical strain may have dislodged the device. Therefore, we believed that both physical strain and small aortic rim were possible causes for device embolism in our patent. We routinely advise to avoid heavy lifting for 3 months in all ASD patients who are treated with percutaneous device closure. Stricter and longer duration of avoidance of heavy lifting should have been recommended for patients with increased risk of device embolism, as in our case. Mashman et al.10) also recommended 6 months of avoidance from strenuous exercise for decreasing embolic risk. Devices usually embolize in the main pulmonary artery.7) If the device embolizes to the pulmonary circulation and impedes pulmonary flow, it may lead to both acute volume and pressure overload of the right ventricular. According to the degree of pulmonary flow impairment, constitutional symptoms usually developed.2) In our patient, it was embolized to the right pulmonary artery. It is fortunate that the device position in the right pulmonary artery was in the longitudinal axis in our patient. Because the pulmonary flow was not influenced by the embolized device, our patient was asymptomatic. If the device is embolized, percutaneous or surgical removal of the device is indicated.7) In our case, percutaneous treatment was not considered because of the orientation of the device in the right pulmonary artery, which precluded snaring the device and the chronicity of the implantation. We subsequently referred the patient to the surgeon.

In conclusion, device embolism, which is the most frequent complication of percutaneous transcatheter closure of ASD, may also occur during late periods of post-implantation. Clinical presentations vary greatly depending on localization and orientation of the embolic device. Rarely, the patients with device embolism can be asymptomatic. Patients at high risk of device embolism must be followed more carefully by echocardiography. In addition, longer duration of avoidance from physical straining must be recommended for patients who have high risk of device embolization.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Chest roentgenogram showing the device outlined within the area of the right pulmonary artery

References

1. Clark EB. Emmanouilides GC, Riemenschneider TA, Allen HD, editors. Epidemiology of congenital cardiovascular malformations. Heart disease infants, children, and adolescent including the fetus and young adult. 1995. 5th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins;60–70.

2. Misra M, Sadiq A, Namboodiri N, Karunakaran J. The 'aortic rim' recount: embolization of interatrial septal occluder into the main pulmonary artery bifurcation after atrial septal defect closure. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007. 6:384–386.

3. King TD, Mills NL. Nonoperative closure of atrial septal defects. Surgery. 1974. 75:383–388.

4. Berdat PA, Chatterjee T, Pfammatter JP, Windecker S, Meier B, Carrel T. Surgical management of complications after transcatheter closure of an atrial septal defect or patent foramen ovale. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000. 120:1034–1039.

5. Hopkins RA, Bert AA, Buchholz B, Guarino K, Meyers M. Surgical patch closure of atrial septal defects. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004. 77:2144–2149.

6. Butera G, Carminati M, Chessa M, et al. Percutaneous versus surgical closure of secundum atrial septal defect: comparison of early results and complications. Am Heart J. 2006. 151:228–234.

7. Chessa M, Carminati M, Butera G, et al. Early and late complications associated with transcatheter occlusion of secundum atrial septal defect. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002. 39:1061–1065.

8. Sinha A, Nanda NC, Khanna D, et al. Morphological assessment of left ventricular thrombus by live three-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2004. 21:649–655.

9. Chiappini B, Gregorini R, Di Eusanio M, et al. Embolization of an Amplatzer atrial septal closure device to the pulmonary artery. J Card Surg. 2008. 23:164–167.

10. Mashman WE, King SB, Jacobs WC, Ballard WL. Two cases of late embolization of Amplatzer septal occluder devices to the pulmonary artery following closure of secundum atrial septal defects. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005. 65:588–592.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download