Abstract

Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) is a rare disorder, but the incidence is increasing and its clinical manifestations are various. We report a case of PCL, which mimics an acute coronary and aortic syndrome. A 51 year-old female was presented with chest pain radiating to the back. Her initial electrocardiogram revealed T wave inversion in the leads of V 5-6, II, III and aVF. Additionally, cardiac troponin-T was slightly elevated. Chest radiography showed marked mediastinal widening. Computed tomography scan showed a huge pericardial mass. The histopathologic findings of the mass were compatible with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. She died of refractory ventricular tachycardia, probably, due to an extensive infiltration of PCL to the myocardium.

Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) is a rare disorder, but the incidence is gradually increasing possibly due to the improvement of diagnostic techniques. The definition of PCL has been changed. Currently, it is defined as a lymphoma presenting as cardiac disease, particularly, if the bulk of the tumor is intrapericardial.1) Clinical manifestations may vary and are attributed to the location of the tumor. In previous literature, the most common presenting features of PCL are congestive heart failure (CHF) and arrhythmia,2-4) but there were no reported cases presenting with acute chest pain, mimicking acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and acute aortic syndrome (AAS). Here, we report a very rapid progressive case of PCL, mimicking ACS and AAS.

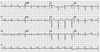

A 51-year-old female with end stage renal disease on hemodialysis and a history of diabetes along with hypertension was presented to the emergency room (ER). She had a problem of continuous resting chest pain, radiating to the back, which started on the previous day. Chest pain did not respond to nitroglycerin. She had smoked a pack a day for the past 15 years. On admission, her blood pressure and heart rate was 110/68 mm Hg and 67 bpm, respectively. An initial electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed T wave inversion in leads V 5-6, II, III and aVF (Fig. 1). Troponin T was slightly elevated to 0.153 ng/mL. We suspected ACS, such as recent myocardial infarction (MI). But, the increased opacity of periaortic area was observed and mediastinal widening was markedly progressed in a chest radiography (Fig. 2A), compared to the previous chest radiography (Fig. 2B). We suspected AAS, such as Stanford type A aortic dissection. For the differential diagnosis, a chest computed tomography (CT) scan was performed. Interestingly, CT scan showed multilobulated soft tissue mass in the pericardial space (Fig. 3A), especially in the right atrioventricular (AV) groove with effacement (Fig. 3B). Also, mild narrowing of the right coronary artery was suspicious, due to a mass and several enlarged lymph nodes observed (Fig. 3C).

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for a close observation. After admission, her chest pain persisted without a change of intensity. The follow-up ECG was not changed, compared to the previous ECG at the ER. Before the biopsy, under general anesthesia, we performed a coronary angiography (CAG) and transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). Significant (80%) tubular eccentric stenosis was observed in a distal left circumflex artery (LCX) on CAG, and the coronary blood flow of LCX was more than Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade 3 (Fig. 4A). However, the right coronary artery was nearly normal (Fig. 4B). We planned to perform a revascularization after a biopsy. TTE also showed 3.46×7.28 centimeter sized pericardial mass around the right ventricle.

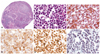

We performed an anterior mini-thoracotomy, through the left 2nd intercostal space incision, with a length of 3 centimeters. Surgical findings showed that the main mass adhered to the heart and major vessels, and it extended to the pericardium and mediastinal pleura. A biopsy was performed at the enlarged lymph node of the left paraaortic area, due to suspicion of mass invasion (Fig. 3C). The low power view on a microscopic exam revealed a diffuse effacement of nodal architecture (Fig. 5A). The high power view revealed the infiltration of monotonous large cells with scanty cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. 5B). On immunohistochemical staining, CD 20 showed a positive finding (Fig. 5C), CD 10 showed faintly positive, and B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 showed partly positive result (Fig. 5D). Also, Ki-67 labeling index was 95% (Fig. 5E), and Epstein-Barr virus in situ hybridization was positive (Fig. 5F). Even though these immunohistochemical staining results could not completely distinguish the diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), from Burkitt's lymphoma, the cellular morphology was close to DLBCL. Although we performed a biopsy at the enlarged lymph nodes, instead of the main mass, radiologic and surgical findings of our case were compatible with that of PCL, according to the currently accepted definition.1) Therefore, we finally diagnosed it as a primary cardiac DLBCL.

Her vital sign was stable after a biopsy. But after one day, heart rhythm suddenly changed to marked bradycardia and asystole. One ample of atropine bolus was injected intravenously and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was immediately performed. Then, heart rhythm changed to ventricular tachycardia (VT). Direct current (DC) cardioversion was performed and heart rhythm changed to sinus rhythm. However, VT continuously occurred and did not respond to DC cardioversion and anti-arrhythmic drugs, though electrolyte, such as potassium, was within normal range. Unfortunately, heart rhythm changed to asystole and she expired.

Acute coronary syndrome and AAS are the most common and important emergency diseases, presenting with acute chest pain. Rapid differential diagnosis is necessary to save the patients in practice. This case initially showed clinical manifestation mimicking ACS and AAS. Therefore, it was essential to rule out ACS and AAS. Interestingly, PCL was diagnosed in this process by accident. Clinical manifestation, which mimics ACS and AAS, was extremely rare in the previous reported PCL. To the best of our search, there was only one case of PCL mimicking acute MI.5) Our case simulated ACS or AAS with symptoms, ECG changes, troponin elevation and chest radiography changes, which were in all likelihood, due to myocardial and pericardial infiltration of PCL. Even though significant stenosis was observed in the distal LCX in our case, the character of chest pain and pattern of cardiac marker, as well as ECG were not changed after admission. In addition, the coronary blood flow of LCX was more than TIMI grade 3 on CAG. Therefore, clinical feature of our case was compatible with the infiltration of PCL, rather than ACS, due to stenosis of the distal LCX.

It was known from the literatures that most of the PCL was located in the right side of the heart and was presented with CHF and arrhythmia.2-4) The common arrhythmia was atrial arrhythmias and AV block.4) We already experienced one case of PCL presenting with AV block.6) However, VT was rarely reported,7-9) probably because VT is a life-threatening arrhythmia that can lead to sudden cardiac death. Our patient also died from sustained VT, probably due to an extensive infiltration of PCL to myocardium. This may have caused a formation of localized re-entrant circuit in an electrically inhomogeneous myocardium.

According to the World Health Organization classification, DLBCL is the most common type of PCL. Our case was also compatible with DLBCL, but had the feature of Burkitt's lymphoma. This feature might be one reason for faster and more aggressive progression than expected. In addition, we could suppose this situation in our case from 95% of Ki-67 labeling index, which is the cellular proliferation

marker.

Primary cardiac lymphoma is now diagnosed with greater frequency, likely because of advances in imaging, although other factors - such as a larger population of HIV-positive or otherwise immunosuppressed patients with longer life expectancy10) - may be contributing to this increase. Therefore, we need to keep in mind of PCL in cardiac, pericardial and mediastinal mass. Also, rapid diagnosis and treatment are necessary to save the patients.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Chest radiography findings: (A) increased opacity of periaortic area was observed and mediastinal widening was markedly progressed in chest radiography compared to (B) chest radiography at 1 year ago.

Fig. 3

Chest computed tomography scan showed (A and B) multilobulated soft tissue mass (arrows) and (C) enlarged lymph nodes (arrows). A and C: coronal view. B: sagittal view.

Fig. 4

Coronary angiography findings. A: significant tubular eccentric stenosis (arrows) was observed in distal left circumflex artery on coronary angiography. B: right coronary artery was nearly normal.

Fig. 5

Histopathologic findings. A: the low power view of microscopic findings reveals entirely efffaced nodal architecture (HE stain, ×40). B: the high power view discloses monotonous large cells with scanty cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (HE stain, ×400). C, D and E: immunohistochemical stainings are as follows: CD20 (+) (C), BCL2 (PARTLY +) (D), Ki-67 labeling index (95% positivity) (E) (×400). F: EBV-ISH shows diffuse positive reactions (×400).

BCL2: B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2, ISH: in situ hybridization, HE: Hematoxylin eosin, EBV: Epstein-barr virus.

References

1. Burke A, Virmani R. Tumors of the heart and great vessels. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. 1996. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology;171–179.

2. Ceresoli GL, Ferreri AJ, Bucci E, Ripa C, Ponzoni M, Villa E. Primary cardiac lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: diagnostic and therapeutic management. Cancer. 1997. 80:1497–1506.

3. Ikeda H, Nakamura S, Nishimaki H, et al. Primary lymphoma of the heart: case report and literature review. Pathol Int. 2004. 54:187–195.

4. Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H. Primary cardiac lymphoma: an analysis of presentation, treatment, and outcome patterns. Cancer. 2011. 117:581–589.

5. Sankaranarayanan R, Prasanna K. A case of primary cardiac lymphoma mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 2009. 32:E52–E54.

6. Cho SW, Kang YJ, Kim TH, et al. Primary cardiac lymphoma presenting with atrioventricular block. Korean Circ J. 2010. 40:94–98.

7. Danbauch SS, Okpapi JU, Maisaka MM, Ibrahim A. Ventricular tachycardia in a patient with lymphocytic (non Hodgkin’s) lymphoma. Cent Afr J Med. 1995. 41:169–171.

8. Miyashita T, Miyazawa I, Kawaguchi T, et al. A case of primary cardiac B cell lymphoma associated with ventricular tachycardia, successfully treated with systemic chemotherapy and radiotherapy: a long-term survival case. Jpn Circ J. 2000. 64:135–138.

9. Tanaka Y, Yamabe H, Yamasaki H, et al. A case of reversible ventricular tachycardia and complete atrioventricular block associated with primary cardiac B-cell lymphoma. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009. 32:816–819.

10. Palella FJ Jr, Baker RK, Moorman AC, et al. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV Outpatient Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006. 43:27–34.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download