Abstract

Background and Objectives

Coronary artery anomalies are found in approximately 1% of patients undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography (CAG). Angiographic recognition of these vessels is important because of their clinical significance and importance in patients undergoing coronary angioplasty or cardiac surgery. There are fairly enough reports concerning the incidence of coronary anomalies in different geographic areas, but this is the first study among the Iranian population.

Subjects and Methods

We reviewed the database of the Catheterization Laboratory of Imam Reza and Shahid Madani Hospitals, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Our inquiry included all patients who referred for CAG from other hospitals, between February 2007 and April 2009. Patients with congenital heart diseases, high "take off" of coronary arteries and separate origin of the conus artery from the right coronary sinus (RCS) were excluded. In total, 6065 films were reviewed.

Results

Seventy nine (1.30%) patients were found to have coronary anomalies. Seventy five (1.24%) patients had anomalies of origin and distribution, while four (0.06%) had coronary artery fistulae. Most common anomaly was separate ostia of the left anterior descending artery and left circumflex artery, which was found in 42 patients (53.16%) with angiographic incidence of 0.69%. The next most common anomalies were anomalous circumflex artery from RCS/right coronary artery (RCA) {n=17 (21.51%)}, and anomalous RCA arising from left coronary sinus {n=6 (7.59%)}.

The widespread application of coronary angiography (CAG) has resulted in congenital coronary artery anomalies being identified more frequently and an improved understanding of the clinical significance of such anomalies. Angiographic recognition of coronary anomalies is of great importance. It is crucial for a surgeon to know the presence of coronary anomalies of origin and distribution, in order to perform optimal cardioplegia and not to cut an anomalous artery. It is similarly crucial for an angiography operator to be aware of coronary anomalies in order not to miss an anomalous vessel. Failure to identify these anomalies can lead to inadequate and prolonged procedures, which can result in catastrophic complications.

The incidence of coronary anomalies in the adult population is approximately 1%, which varies on angiographic and postmortem studies.1)2) Although generally benign in character, some coronary artery anomalies are associated with more serious clinical outcomes, such as congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, syncope and sudden death.3-9)

Anomalous coronary arteries can be grouped into three general categories. As a general guide, anomalies can be divided into three general classifications. These include, 1) anomalies of origination and course (ectopic ostium within proper sinus, ostium outside normal sinus, and absent vessel), 2) anomalies of intrinsic coronary arterial anatomy (congenital stenosis of ostium, congenital aneurysms, and myocardial bridging), and 3) anomalies of coronary termination (fistulae).

We reviewed the database of the Catheterization Laboratory of Imam Reza and Shahid Madani Hospitals (Tabriz, Iran). All adult patients (>18 years), who referred for diagnostic CAG between February 2007 and December 2009, were included. Six thousand sixty-five films were reviewed and those with definite and suspected anomalous coronary arteries were selected for further assessment by two experienced interventionists before being finally classified. Differences in opinions were settled through discussion and consensus. The study was approved by the institutional review committee of Tabriz University of medical sciences.

Patients with congenital heart diseases, high "take off" of coronary arteries and separate origin of the conus artery, from the right coronary sinus (RCS), were excluded. Patients were considered as having significant coronary artery disease (CAD), if they had more than 50% constriction of intraluminal diameter.

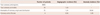

Out of 6065 patients, 79 (1.30%) had coronary anomalies. This group included 58 males and 21 females, with age range between 34 to 84 years. A total of 75 (1.24%) patients had anomalies of origin and distribution, while 4 (0.06%) had coronary artery fistulae (Table 1).

Two patients underwent CAGs prior to valve replacement or percutaneous transmitral mitral comissurotomy, one to evaluate the function of prosthetic mitral valve and coronary vessels, due to chest pain. The remaining CAGs were carried out to evaluate the chest pain to detect or rule out atherosclerotic CAD. Table 2 shows incidence of different coronary anomalies in our angiographic population.

The most common anomaly was separate origins of left anterior descending artery (LAD) and left circumflex artery (LCX) from left coronary sinus (LCS), which was present in 42 (53.16%) patients with angiographic incidence of 0.69% (Fig. 1).

The second common anomaly was anomalous circumflex artery (CX) from RCS/right coronary artery (RCA), observed in 17 patients (11 from RCS and 6 from RCA), accounting for 21.51% of our anomalies with angiographic incidence of 0.28%. These anomalies were originating from RCS/RCA and coursing posterior to Aorta with normal peripheral distribution (Fig. 2). In all cases, the Cx virtually traveled behind the aorta to lie in the left atrioventricular (AV) groove. In one patient, besides an aberrant LCX, LAD had a muscle bridge at the mid portion. Another patient also had separate origins of conus artery and concomitant severe aortic regurgitation. Among these 17 patients, 10 had CAD that undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (Fig. 2A).

Anomalous RCA arising from LCS was observed in 6 (7.59%) patients with angiographic incidence of 0.10%. In all cases, RCA was originating from an orifice located anterior to the left main coronary artery (LMCA) ostium in LCS, and had interarterial course before reaching the right AV groove (Fig. 3). All 6 patients had severe atherosclerosis, accounting for 7.59% of all anomalies.

Left coronary artery (LCA) arising from RCS was observed in 3 (3.80%) patients with angiographic incidence of 0.05%. The course was interarterial in two and septal in one of the patients (Fig. 4).

Two (3.80%) patients had type I single coronary artery (SCA) with angiographic incidence of 0.03%. There was no ostium in RCS, and the territory of RCA was supplied by the continuation of LCX artery (Fig. 5). Only one (1.27%) patient had type II SCA with angiographic incidence of 0.02%. It was arising from RCS by the main stem, and then bifurcating into the right and left coronary arteries. RCA passed its normal course in the right AV groove. LCA, after passing between the aorta and main pulmonary trunk, bifurcated into LAD and LCX, which followed their usual course.

This anomaly was present in one (1.27%) patient with angiographic incidence of 0.02%. All 3 coronary arteries were arising from RCS by separate ostia. Their distribution was normal, but LAD was diminutive and didn't reach the apex and had septal course of its proximal part. Apex was supplied by posterior descending artery (PDA), which was the branch of the dominant RCA. LCX had a retroaortic course and supplied the whole lateral left ventricle (LV) wall (Fig. 6).

This rare anomaly was observed in only one (1.27%) patient - a 49-year-old woman - with angiographic incidence of 0.02%. LCA was arising from pulmonary artery (PA) and was filling retrogradely via RCA. Both coronary arteries were enlarged, especially RCA, but they were free of disease (Fig. 7).

Coronary artery fistulae were present in four (5.06%) patients with angiographic incidence of 0.07%. Fistulae were present between LAD to left atrium (LA) in one patient, between LAD and PA in one patient and between coronary and LV in two patients. In the last two fistulae, coronary arteries were draining into LV. In one of them, it was particularly severe. This patient had no coronary sinus, even no developed venous system of the heart. The patient with LAD to LA fistulae had severe mitral stenosis and moderate mitral regurgitation.

Aberrant CX from RCS was seen in one (1.27%) patient with angiographic incidence of 0.02%, with large obtuse marginalis (OM), arising from LCA (Fig. 8). We named this anomaly "divided LCX", as we couldn't find reports of such an anomaly in the literature.

We had a patient with very interesting coronary anomaly, which, to our knowledge, had not been reported before. He had a SCA from RCS. LAD was arising from RCS and had anterior course before it reached its normal place in the anterior interventricular groove, gave rise to some septal branches, and vascularised the apex. Aberrant CX had retroaortic course and was significantly diseased at the proximal part. RCA passed its normal course and was cut off from its mid portion with good distal run off. The most interesting was the fact that he had an additional great artery arising from LCS. After passing an approximate course of LMCA and proximal part of LAD, it bifurcated into the main septal and main diagonal branches, and was terminated immediately after that bifurcation. The ejection fraction of the patient's heart was 15 to 20%. We named this anomaly "divided LAD".

Although coronary artery anomalies are very rare, many researchers are interested in this subject. Some retrospective angiographic studies have been published, assessing the incidence of different coronary anomalies. There are many reports describing the coronary anomalies, but this is the first report about the incidence and pattern of anomalous coronary arteries among the Iranian population. Worldwide incidence has been described previously. We found an overall incidence of congenital anomalous aortic origin of the coronary artery of 1.3% among patients undergoing coronary artery angiography; this is in agreement with the 0.16-1.3% incidence reported in other series.7-9)12-15) Anomalous coronaries prevailed among males, possibly due to the fact that more angiograms were done among male patients.

The most common anomaly in our study was the separate origin of LAD and LCX from the LCS. This anomaly causes no hemodynamic impairment and is considered to be benign. The appearance of an avascular area at the site of the LMCA distribution should raise a suspicion to the separate origin of LAD and LCX. Its incidence is very variable because of great operator dependence. In series by Yamanaka, the incidence was reported as 35.3%,1) while it was only 5% in the study of Göl et al.15) The point is that most researchers analyze angiography reports and choose only reports with coronary anomalies. They do not view all films, and thus, they are likely to miss some cases. And vice versa, a case defined as a separate LAD and LCX by one operator, could be defined as a short left main stem by another one. But we have reviewed all 6065 angiography films, one by one, picking up suspicious ones and then watched and discussed them with experienced interventionists.

The Cx may arise from the RCS or as an early branch of the RCA. When present, the Cx virtually always travels behind the aorta to lie in the left AV groove. The next commonly encountered anomaly in our series was the CX arising from RCS/RCA, which constituted 22.78% of all anomalies; however, Aydinlar et al.7) reported 11% incidence. It should be suspected in the presence of unusually long non-branching proximal LMCA and a non-perfused lateral wall. A cardiac surgeon should be informed concerning this anomaly in order to avoid accidental compression of the vessel during a valve replacement. This anomaly is considered to be benign.

The third common anomaly with 7.59% incidence was the RCA arising from LCS. It should be noted that this was the most common anomaly (38.5%) in the study by Garg et al.12) In this anomaly, the RCA originates from an orifice located anterior to the left main ostium in the LCS. This anomaly is suspected when RCA ostium is not located in the RCS and collaterals are absent. This ectopic RCA is difficult to cannulate because of a slit-like orifice and odd angulation. Myocardial ischemia can be due to a slit-like orifice, acute angulation and compression of vessel between aorta and pulmonary trunk, besides of atherosclerotic coronary disease.

Left main coronary artery was arising from RCS in 3 patients, which made up 3.8% of anomalies. This is quite a rare anomaly. Yamanaka and Hobbs1) found 22 cases among 126595 patients (0.01%). LMCA is arising by a separate ostium from RCS and can take 4 different courses: posterior, septal, interarterial and anterior, before bifurcating into LAD and LCX. Of these, only interarterial type is considered to be dangerous. As such, it can lead to slit-like orifice of LMCA ostium and compression of the LCA between the aorta and pulmonary trunk during strenuous exercise, resulting in myocardial ischemia and cause sudden cardiac. The septal type is the most common one according to the literature, although we came across 2 interarterial and 1 septal courses in our patients.

We had three cases (3.8%) of SCA. This is also a rare anomaly. In patients with a SCA, sudden death has been reported to be associated with a major coronary artery coursing between the aorta and main pulmonary artery.16) Only 5 case reports of coronary intervention for a single anomalous coronary artery from the English17-21) and 2 cases from the Japanese literature have been published.22) It should be noted, that in their study, Garg et al.12) did not come across a SCA among 4100 patients. There were 56 cases of SCA among 126595 patients who underwent CAGs in the study by Yamanaka et al.1) The most common type in their research was L-I, followed by R-II and L-II in the above mentioned study. Two of our patients had type I SCA. There was no ostium in the RCS and the territory of RCA was supplied by the continuation of LCX artery. We came across only one patient with type II SCA. It was arising from the RCS by the main stem, which was then bifurcating into the right and left coronary arteries. RCA passed its normal course in the right AV groove. LCA, after passing in between the aorta and main pulmonary trunk, bifurcated into LAD and LCX, which followed their usual course.

It is important to identify the course as it relates to the great vessels, because if it courses between the aorta and the pulmonary artery, symptoms may occur.1)

We had one patient with a very rare anomaly of all three coronary coronary arteries, arising separately from RCS. Harikrishnan et al.9) encountered only one such case, among the 7400 angiograms reviewed. Also, in a report by Göl et al.15) they came across only one case among 58023 patients. In our patient, all 3 coronary arteries were arising from the RCS with separate ostia. Their peripheral distribution was normal. Proximal part of LAD had septal course. LAD was diminutive and did not reach the apex. Apex was supplied by PDA, which was a branch of the dominant RCA. LCX had a retroaortic course and supplied the whole lateral LV wall and big part of anterior LV wall. All coronary arteries were free of disease.

An anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) is one of the rare anomalies present in 1 out of 300000 live births.16) This anomaly may cause myocardial ischemia or infarction, mitral insufficiency, congestive heart failure, and death. We came across only one patient - 49 years old woman - with ALCAPA in our series. The LCA was arising from PA and was filling retrogradely via RCA. Both coronary arteries were enlarged, especially RCA, but free of atherosclerotic disease. It is known that this anomaly was more often present in patients with congenital heart disease, especially Tetralogy of Fallot. But, as it was noted previously, we didn't include patients with congenital heart disease in our research.

Although the literature suggests that the majority of coronary artery fistulae open into the RV, right atrium, and CS, and less common into the PA, LA, or LV,7) we obtained the opposite results. We encountered 4 patients with significant coronary-to-cameral fistulae. Two of them had coronary-to-LV, while others had coronary-to-PA and -LA fistulae.

We came across 2 very rare anomalies, which to best of our knowledge, had not been reported before. The first was the patient with aberrant CX from RCS, which had an additional main OM artery, arising from the LCA, from its normal side. LCX had a retroaortic course. All arteries were free of disease. We named this anomaly "divided LCX". The second patient had a SCA arising from the RCS. LAD had an anterior course before it reached its normal place in the anterior interventricular groove, gave rise to some septal branches, and vascularised the apex. It was significantly diseased at the distal part. Aberrant CX had a retroaortic course and was significantly diseased at the proximal part. We named this anomaly "divided LAD".

There is some reports on atherosclerotic disease in anomalous coronary arteries with the incidence of about 32-66.66%.9)12) An interesting finding in our study series, was severe atherosclerosis of all anomalous RCA arising from LCS. Other studies have proposed no probability of atherosclerotic involvement of an anomalous RCA.9) Garg et al.12) reported CAD restricted to anomalous artery in 10.25% of cases. They concluded that there does not appear to be an increased risk for development of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease in anomalous coronary arteries.9)

In conclusion, anomalous coronary arteries are a rare group of pathologies, with a variety of clinical manifestations related to their course. Greater awareness of their existence, clinical significance and treatment options will lead to better management of this entity. Angiographic recognition of these vessels is important because of their clinical significance and importance in patients undergoing coronary angioplasty or cardiac surgery. In general, the incidence and pattern of coronary anomalies in our study was similar to earlier reports from different parts of the world.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Seperated LAD & LCX. Separate origins of LAD and LCX from the left coronary sinus. LAD: left anterior descending artery, LCX: left circumflex artery.

Fig. 2

Anomalous circumflex artery from the right coronary sinus (RCS)/right coronary artery. A: in one patient, left circumflex artery originates from right coronary sinus with significant coronary artery disease (arrow=lesion). B: another patient also had separate origins of conus artery and concomitant severe aortic regurgitation.

Fig. 3

RCA arising from LCS. RCA is originating from an orifice located anterior to LMCA ostium in the LCS and had interarterial course before reaching the right atrioventricular groove. RCA: right coronary artery, LCS: left coronary sinus, MLCA: left main coronary artery.

Fig. 4

LMCA arising from right coronary sinus. A: in this patient LMCA courses between aorta and pulmonary artery. B: a patient with anomalous LMCA with septal course. LMCA: left main coronary artery.

Fig. 5

Single coronary artery. Type I single coronary artery: the territory of right coronary artery is supplied by the continuation of left circumflex artery artery. A and B are different views of one patient and C, D and E are different views of another patient.

Fig. 6

Separated 3 coronary arteries. All 3 coronary arteries arising from right coronary sinus with separate osita. Distribution is normal. A: left anterior descending artery is diminutive and does not reach the apex and has septal course of its proximal part. B: circumflex artery originates from separate ostia and courses behind the aorta.

Fig. 7

Anomalous LCA from pulmonary artery. LCA is arising from pulmonary artery and was filing retrogradely via RCA. Both coronary arteries are enlarged, especially RCA. LCA: Left coronary artery, RCA: right coronary artery.

Fig. 8

Divided left circumflex artery. A: large obtuse marginalis, arising from left coronary artery. B: Aberrant circumflex artery from right coronary sinus.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by Vice Chancellor for Research, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The authors are indebted to Cardiovascular Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran for its support.

References

1. Yamanaka O, Hobbs RE. Coronary artery anomalies in 126,595 patients undergoing coronary arteriography. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1990. 21:28–40.

2. Cieslinski G, Rapprich B, Kober G. Coronary anomalies: incidence and importance. Clin Cardiol. 1993. 16:711–715.

3. Cheitlin MD, De Castro CM, McAllister HA. Sudden death as a complication of anomalous left coronary origin from the anterior sinus of Valsalva, A not-so-minor congenital anomaly. Circulation. 1974. 50:780–787.

4. Chaitman BR, Lespérance J, Saltiel J, Bourassa MG. Clinical, angiographic, and hemodynamic findings in patients with anomalous origin of the coronary arteries. Circulation. 1976. 53:122–131.

5. Kragel AH, Roberts WC. Anomalous origin of either the right or left main coronary artery from the aorta with subsequent coursing between aorta and pulmonary trunk: analysis of 32 necropsy cases. Am J Cardiol. 1988. 62(10 Pt 1):771–777.

6. Lee J, Choe YH, Kim HJ, Park JE. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstration of anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the left coronary sinus associated with acute myocardial infarction. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003. 27:289–291.

7. Aydinlar A, Ciçek D, Sentürk T, et al. Primary congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries: a coronary arteriographic study in Western Turkey. Int Heart J. 2005. 46:97–103.

8. Barriales Villa R, Morís C, López Muñiz A, et al. [Adult congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries described over 31 years of angiographic studies in the Asturias Principality: main angiographic and clinical characteristics]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2001. 54:269–281.

9. Harikrishnan S, Jacob SP, Tharakan J, et al. Congenital coronary anomalies of origin and distribution in adults: a coronary arteriographic study. Indian Heart J. 2002. 54:271–275.

10. Kurjia HZ, Chaudhry MS, Olson TR. Coronary artery variation in a native Iraqi population. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1986. 12:386–390.

11. Topaz O, DiSciascio G, Cowley MJ, et al. Absent left main coronary artery: angiographic findings in 83 patients with separate ostia of the left anterior descending and circumflex arteries at the left aortic sinus. Am Heart J. 1991. 122:447–452.

12. Garg N, Tewari S, Kapoor A, Gupta DK, Sinha N. Primary congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries: a coronary: arteriographic study. Int J Cardiol. 2000. 74:39–46.

13. Ouali S, Neffeti E, Sendid K, Elghoul K, Remedi F, Boughzela E. Congenital anomalous aortic origins of the coronary arteries in adults: a Tunisian coronary arteriography study. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2009. 102:201–208.

14. Correia E, Ferreira P, Rodrigues B, et al. Prevalence of anomalous origin of coronary arteries: a retrospective study in a Portuguese population. Rev Port Cardiol. 2010. 29:221–229.

15. Göl MK, Ozatik MA, Kunt A, et al. Coronary artery anomalies in adult patients. Med Sci Monit. 2002. 8:CR636–CR641.

16. Lipton MJ, Barry WH, Obrez I, Silverman JF, Wexler L. Isolated single coronary artery: diagnosis, angiographic classification, and clinical significance. Radiology. 1979. 130:39–47.

17. Chan CN, Berland J, Cribier A, Letac B. Angioplasty of the right coronary artery with origin of all three coronary arteries from a single ostium in the right sinus of Valsalva. Am Heart J. 1993. 126:985–987.

18. Lawton J, McGrath J, Jones JS, Dehmer GJ. Treatment of coronary artery disease in an anomalous coronary artery by placement of an intracoronary stent. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1997. 41:185–188.

19. Hsu LA, Chu PH, Ko YS, Ko YL, Chiang CW. Transluminal coronary angioplasty and stenting in a patient with single coronary artery and acute myocardial infarction. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1997. 20:299–303.

20. Gambhir DS, Singh S, Bharadwaj S, Arora R. Rotablation and elective stenting of stenosis in the left anterior descending coronary artery arising from an anomalous single coronary artery. Indian Heart J. 2000. 52:459–460.

21. Stefenelli T, Wutte M, Madl C, Weissel M. Emergency angioplasty and stent deployment for acute occlusion of an anomalous single coronary artery (all three coronary arteries from one ostium in the right sinus of Valsalva). Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2001. 113:138–140.

22. Ohta H, Sumiyoshi M, Suwa S, et al. Primary coronary angioplasty with stenting for acute coronary syndrome in patients with isolated single coronary artery: a report of 2 cases. Jpn Heart J. 2003. 44:759–765.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download