Abstract

Nowadays, we have a better understanding of the natural history of constrictive pericarditis such as transient constriction. In addition, we have acquired the correct understanding of hemodynamic features that are unique to constrictive pericarditis. This understanding has allowed us to diagnose constrictive pericarditis reliably with Doppler echocardiography and differentiation between constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy is no longer a clinical challenge. The advent of imaging modalities such as CT or MR is another advance in the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis. We can accurately measure pericardial thickness and additional information such as the status of coronary artery and the presence of myocardial fibrosis can be obtained. We no longer perform cardiac catheterization for the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis. However, these advances are useless unless we suspect and undergo work-up for constrictive pericarditis. In constrictive pericarditis, the most important diagnostic tool is clinical suspicion. In a patient with signs and symptoms of increased systemic venous pressure i.e. right sided heart failure, that are disproportionate to pulmonary or left sided heart disease, possibility of constrictive pericarditis should always be included in the differential diagnosis.

In typical constrictive pericarditis, diastolic filling of the heart is inhibited because of chronic fibrous thickening of the wall of pericardial sac. Descriptions of diseases of the pericardium have a long history (Table 1) and date back as far as Egyptian and Greek civilizations. Historically, the eponym "Pick's disease" was given to constrictive pericarditis with ascites and hepatomegaly,1) which implies that these patients may be misdiagnosed as having chronic liver disease. In the past, we also experienced a patient who was referred under the impression of nephrotic syndrome because of the combin-ation of ascites and proteinuria, and turned out to have constrictive pericarditis. Although coming to an accurate diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis is sometimes challenging, efforts to get a correct diagnosis is critical as this condition can usually be completely cured.

Most causes of acute pericarditis (Table 2) could be a possible cause of chronic constrictive pericarditis. However, sometimes patients with idiopathic/viral pericarditis are unduly informed of developing constrictive pericarditis. In a study assessing the risk of constrictive pericarditis following a first episode of acute pericarditis2) in 500 patients over a mean follow-up of six years (24 to 120 months), constrictive pericarditis developed in only 2 of 416 patients with idiopathic/viral pericarditis. Even in recurrent pericarditis, the development of constrictive pericarditis was low in this subset of patients.3)

The causes of constrictive pericarditis can be varied. Tuberculosis accounted for 49% of cases of constrictive pericarditis in a series reported in 1962,4) but tuberculosis is now only a rare cause of constrictive pericarditis in developed countries. However, it should be considered as a possible etiology in countries where prevalence of active tuberculosis is still high and in patients with HIV infection. In the modern era, we are more concerned about etiologies such as post-cardiac surgery or post-radiation therapy. This is not only because of the recent increase in the incidence of these etiologies, but also because of the relatively poor prognosis of these entities.5)6)

Traditionally, diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis has been accomplished by demonstrating both, 1) calcified pericardium or increase in pericardial thickness, and 2) presence of constrictive physiology.

This can be done by a number of imaging modalities. However, in a recent report, 18% of patients (26 out of 143 patients) showed normal thickness pericardium in proven constrictive pericarditis. Therefore, one should not exclude the possibility of constrictive pericarditis even in the absence of this finding if clinically suspected.

Although not sensitive enough for the clinician to be satisfied, chest X-ray findings (Fig. 1) can occasionally give us the possibility of constrictive pericarditis, that may have been missed. To get the best information from the chest X-ray, both lateral and PA projection images should be obtained.

To get direct visualization of the pericardium, direct measurement of pericardial thickness can be performed by either computed tomographic (CT) scanning (Fig. 2) or magnetic resonance (MR) im-aging.1)7-10) One can consider the pericardium to be thickened when the pericardial thickness is greater than 2 mm in diameter. In addition to the fact that a considerable proportion of patients with constrictive pericarditis can show a normal thickness pericardium as already mentioned, the finding of a thickened pericardium is not necessarily diagnostic of constrictive pericarditis. Some patients may have pericardial thickening without evidence of constriction. For example, some degree of pericardial reaction can manifest as an increase in the pericardial thickness, and may be present without a hemodynamic effect in patients who have had radiation therapy or an open heart operation.

Both CT and MR can give anatomic information other than pericardial thickness, such as critical vascular abnormality or extent of lung injury. In addition to these advantages, when the CT is utilized, one can avoid the need for invasive coronary angiography in those with normal CT coronary angiography. One potential advantage of MR over CT is that it can obtain information that can be derived from the late gadolinium enhancement findings. MRI can give us information about pericardial inflammation and pericardial-myocardial adherence11) as well as myocardial fibrosis that may be involved in the clinical improvement after pericardiectomy.

In the past, hemodynamic findings that are peculiar to constriction had not been accurately understood.12)13) Based on the incomplete understanding of constrictive physiology, it had been our understanding that cardiac catheterization is the gold standard for reliable evaluation of the presence or absence of constrictive physiology. Cardiac catheterization findings include an increase and equalization of end diastolic pressures in all four cardiac chambers, a dip and plateau pattern in the ventricular pressure curves, and rapid x and y descents in the atrial pressure curves (Fig. 3). As these findings are not peculiar to the constrictive physiology, these findings also may be present in patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy. Therefore, differentiation between constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy has always been a challenging clinical problem.

In 1989, Hatle et al.14) reported the two characteristic features in constrictive pericarditis. Firstly, they showed dissociation between intrathoracic and intracardiac pressures. In normal persons, inspiration causes a decrease in both the intrathoracic and intracardiac pressures. Therefore, during inspiration, there is a simultaneous fall in intrathoracic and intracardiac pressures and, there is no change in the driving pressure from the lungs into the left-sided chambers. However, in a patient with constrictive pericarditis, decrease in intrathoracic pressure is not transmitted to the left sided chambers because of the rigid pericardium, and during inspiration, there is a lower driving force from the lungs into the left side of the heart and the left ventricle becomes underfilled. Secondly, enhanced ventricular interaction can also occur. As both ventricles are sharing the same limited space, chamber size and function of one ventricle affects the other ventricle, and this interaction is enhanced in constrictive pericarditis. In patients with constrictive pericarditis, the left ventricle is under filled during inspiration and there is a reciprocal increase in filling of the right ventricle. Conversely, during expiration there is decreased filling of the right ventricle and increased filling of the left ventricle.

These two unique features of constrictive pericarditis can accurately be evaluated by Doppler echocardiography.15)16) As these features are not present in restrictive cardiomyopathy, differentiation between constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy can reliably be done by Doppler echocardiography. Doppler echocardiographic findings include 1) prominent (usually over 25%) increase in mitral E velocity during expiration and decrease during inspiration and, 2) increase in diastolic flow reversal in the hepatic venous flow during expiration (Figs. 4 and 5).

Although Doppler echocardiography is a potent tool in detecting the presence of constrictive physiology, one should keep in mind se-veral pitfalls, for example respiratory variation in the mitral inflow may not be present in about 20% of the patients.17)18) In certain proportion of these patients without respiratory variation in the mitral inflow, absence of respiratory variation may be due to the volume status of the patient. Therefore, respiratory variation can be elicited by preload reduction with semi-recumbent (rather than supine) positioning or diuretic administration in patients with markedly elevated left atrial pressure.19) In the opposite situation with volume depleted state, respiratory variation can be elicited by leg raising (Fig. 6). Another pitfall is that respiratory variation in the mitral inflow is not unique to constrictive pericarditis. This variation can be seen in chronic obstructive lung disease and in situations when the pericardial constraint becomes manifested by severe left or right ventricular dilatations. A final pitfall is that in the evaluation of hepatic vein flow, one should be cautious in patients with rapid respiratory rate as the respiratory cycle from inspiration to expiration may change in every cardiac cycle, therefore, mimicking constrictive physiology (Figs. 7 and 8).

Although we can reliably diagnose constrictive pericarditis with Doppler echocardiography, it is not always easy to get diagnostically meaningful Doppler signals because of low image quality and patient cooperation is needed in the evaluation of respiratory variation. Therefore, evaluation of mitral annulus velocity (E' velocity) in patients with constrictive pericarditis is sometimes very useful. In constrictive pericarditis, as the dilatation of chambers in the short axis direction is limited because of the thickened pericardium, there is a compensatory increase in chamber dilatations in the long axis direction. Therefore, E' is usually well preserved or even accentuated (Fig. 9).18) This unique feature of mitral annulus velocity in constrictive pericarditis is especially useful in differential diagnosis between constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy. In contrast to constrictive pericarditis, restrictive cardiomyopathy, which is a myocardial disease, nearly always shows depressed E' velocity.17)20) In addition to the preserved or accentuated E' velocity in constrictive pericarditis, a recent study showed that medial E' velocity in patients with constrictive pericarditis is higher than the lateral E' velocity, which is the opposite phenomenon in usual situations, and this phenomenon is reported to be useful during the diagnosis.21)22)

Because of the well preserved or even accentuated E' velocity in constrictive pericarditis, we should keep in mind that, E/E' ratio which has been widely used in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressure shows an inverse relationship to left ventricular filling pressure.23) Therefore, it cannot be applied in the estimation of filling pressure in patients with constrictive pericarditis.

As discussed in Doppler echocardiography, interventricular dependence is exaggerated in constrictive pericarditis, which implies that in the M-mode or 2D echocardiography respiratory variation of the ventricular size can be observed (Fig. 10). However, before the advent of our current understanding of constrictive physiology, a number of other indirect signs have been used in the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis and these findings are as follows: 1) thickening of the pericardium, which may be more reliably estimated by transesophageal echocardiography24); 2) abnormal septal motion; 3) flattening of the left ventricular posterior wall during diastole; and 4) dilatation of the inferior vena cava.25)26) Although one can suspect the presence of constrictive pericarditis with M-mode or 2D echocardiographic findings, these findings are not sensitive or specific for the confirmative diagnosis of constriction. Therefore, one should resort to echo-Doppler findings for the diagnosis.

History taking and physical examination are not an obsolete process in the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis. When encountered by physical findings representing increased systemic venous pressure, such as increase in jugular venous pressure, ascites, hepatosplenomegaly and edema, the possibility of constrictive pericarditis should considered. For example, patients with constrictive pericarditis can be accompanied by proteinuria of the nephrotic range and protein loosing enteropathy. If the physician does not notice increased jugular pressure in the physical examination, the patient may unnecessarily undergo examination such as kidney biopsy or colonoscopic examination.

It is worth mentioning that in addition to increased pressure, jugular pressure waveform is quite characteristic. As the right atrial pressure waveform shows an M or W shape because of the prominent Y descent in addition to the preserved X descent, jugular venous waveform is seen by the naked eye as "hyperdynamic" as we usually perceive descent as a collapse. Therefore, it is not difficult to tell the pressure waveform in patients with constrictive pericarditis as abnormal.

During history taking, possible predisposing conditions that can lead to constrictive pericarditis should be focused on.

Symptoms related to constrictive pericarditis can be improved by removing the pericardium surgically and pericardiectomy is the only definitive treatment option for patients with chronic constrictive pericarditis. Medical therapy such as diuresis may be used as a temporary measure and for patients who cannot undergo surgery.

However, constriction may be transient or reversible in a minority of patients with constrictive pericarditis. Thus, patients with newly diagnosed constrictive pericarditis may be given a trial of conservative management for two to three months before pericardiectomy is recommended.

Even in patients who are planning for pericardiectomy, deciding the timing of surgery is sometimes difficult because pericardiectomy is technically difficult if pericarditis is still in the effusive or adhesive state. On the other hand, if the surgery is performed too late, lower extremity edema may persist even after the relief of systemic venous hypertension because of deep vein incompetence. Here, MR imaging might be helpful in obtaining information about the state of pericardial inflammation and pericardial-myocardial adherence.11) Traditionally, pericarditis has been classified as acute, subacute and chronic (Table 3), and we used to rely on the stage of pericarditis when considering pericardiectomy.

Pericardiectomy has a significant operative mortality of 5-7% even recently.27)28) Therefore, recommendation of surgery should be done very cautiously in patients with either mild or very advanced disease and in whom prognosis after pericardiectomy was reported to be poor,5)6) e.g., those with radiation-induced constriction, myocardial dysfunction, significant renal dysfunction, or mixed const-rictive-restrictive disease. In the past, heavy calcification on chest X-ray had been regarded as a relative contraindication to surgery.

A subset of patients with constrictive pericarditis undergoes spontaneous resolution of constrictive pericarditis or responds to medical therapy29) usually in average 8 weeks. The causes for transient constrictive pericarditis are diverse, the most common being prior cardiovascular surgery (25%). Most frequent treatment has been nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A recent study30) showed a promising role of MR imaging in predicting which patients with constrictive pericarditis will have reversal or resolution of the process. In this study, late gadolinium enhancement pericardial thickness ≥3 mm had 86% sensitivity and 80% specificity in predicting reversibility.

Diagnosis of occult constrictive pericarditis31) had made symptomatic patients whose hemodynamic findings are not overt at the resting state but could have been elicited by expanding volume status by saline infusion. It was also reported that symptoms of the patients improved after pericardiectomy. We can understand the hemodynamic status in these patients, but it is uncertain that patient's symptoms were related to the occult constriction.

Diagnosis of effusive-constrictive pericarditis can be made in patients with hemodynamic constriction who also have significant amount of pericardial effusion. Hemodynamically, tamponade and constrictive physiology can co-exist. Therefore, when only the presence of pericardial effusion was appreciated in patient with this entity, drainage of pericardial effusion will not result in the complete resolution of systemic congestion. Therapeutically, this situation usually implies that an active inflammatory process is ongoing. Therefore, it is usually not an optimal timing for pericardiectomy and depending on the etiology, constrictive physiology can be reversible.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Pericardial calcification in a patient with constrictive pericarditis. In this patient with end-stage renal disease with multiple physical signs of increased systemic venous pressure, we can come to the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis for sure with this chest X-ray finding even in the absence of further diagnostic tests.

Fig. 2

Increase in pericardial thickness seen in a computed tomographic image. Arrows: thickened pericardium.

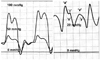

Fig. 3

Classic cardiac hemodynamic findings in constrictive pericarditis. When the pericardial pressure is increased above the left atrial pressure, both left and right atrial pressure increase to the level of the pericardial pressure, resulting in the equalization of the left and right atrial pressures. During diastole, as the mitral and tricuspid valves are opened, this equalization in both atrial pressures results in equalization of four chamber pressures. In constrictive pericarditis, ventricular filling is not limited during early diastole but is limited during mid to late diastole. This feature results in dip and plateau patterns in both ventricular pressure waveforms and rapid Y descent in atrial pressure waveforms. In the atrial pressure waveforms, in association with the preserved X descent, this prominent Y descent results in M or W shaped atrial pressure waveforms.

Fig. 4

Schematic representation of the mechanism of respiratory variations in the mitral inflow and hepatic venous flow. BA: right atrium, RV: right ventricular, LA: left atrium, LV: left ventricular, PV: pulmonary vein, HV: hepatic venous flow. Reprinted from Oh JK et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 23:154-62, 1994 with permission.15)

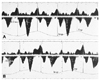

Fig. 5

A: mitral inflow finding in constrictive pericarditis. Prominent increase in mitral E velocity during expiration is seen. B: hepatic vein flow. Diastolic flow reversal during expiration (arrows) is seen. MV: mitral inflow, HV: hepatic venous flow, insp: inspiration, exp: expiration.

Fig. 6

In a relatively volume depleted state, respiratory variation in the mitral inflow may not be present, and can be elicited when the intracardiac volume is increased by leg raising. A: respiratory variation in the mitral inflow is absent in the resting state. B: respiratory variation is manifested after leg raising.

Fig. 7

Hepatic vein flows obtained in a single patient. A: expiratory diastolic flow reversal characteristic feature in constrictive pericarditis is suspected. B: absence of increase in diastolic flow reversal during expiration. Only prominent A waves are seen in every cardiac cycle. Insp: inspiration, Exp: expiration.

Fig. 8

Although timing of respiratory change from inspiration to expiration may not be accurately reflected in the respirometer, (A) shows every cardiac cycle located during one phase of respiration, while (B) shows that respiratory change from inspiration to expiration or vice versa occur in the midst of every cardiac cycle. Insp: inspiration, Exp: expiration.

Fig. 9

Mitral annulus velocity in a patient with constrictive pericarditis before (A) and after (B) pericardiectomy. Mitral annulus velocity decreased after pericardiectomy when the constrictive physiology was relieved.

References

1. Fowler NO. Constrictive pericarditis: its history and current status. Clin Cardiol. 1995. 18:341–350.

2. Imazio M, Brucato A, Maestroni S, et al. Risk of constrictive pericarditis after acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2011. 124:1270–1275.

3. Imazio M, Brucato A, Adler Y, et al. Prognosis of idiopathic recurrent pericarditis as determined from previously published reports. Am J Cardiol. 2007. 100:1026–1028.

4. Robertson R, Arnold CR. Constrictive pericarditis with particular reference to etiology. Circulation. 1962. 26:525–529.

5. Bertog SC, Thambidorai SK, Parakh K, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004. 43:1445–1452.

6. Ling LH, Oh JK, Schaff HV, et al. Constrictive pericarditis in the modernera: evolving clinical spectrum and impact on outcome after pericardiectomy. Circulation. 1999. 100:1380–1386.

7. Masui T, Finck S, Higgins CB. Constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1992. 182:369–373.

8. Breen JF. Imaging of the pericardium. J Thorac Imaging. 2001. 16:47–54.

9. Maisch B, Seferović PM, Ristić AD, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; the Task Force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004. 25:587–610.

10. Kojima S, Yamada N, Goto Y. Diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis by tagged cine magnetic resonance imaging. N Engl J Med. 1999. 341:373–374.

11. Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, Lytle BW, Desai MY, Klein AL. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010. 3:333–343.

12. Connolly DC, Wood EH. Cardiac catheterization in heart failure and cardiac constriction. Trans Am Coll Cardiol. 1957. 7:191–201.

13. Meaney E, Shabetai R, Bhargava V, et al. Cardiac amyloidosis, contrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1976. 38:547–556.

14. Hatle LK, Appleton CP, Popp RL. Differentiation of constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy by Doppler echocardiography. Circulation. 1989. 79:357–370.

15. Oh JK, Hatle LK, Seward JB, et al. Diagnostic role of Doppler echocardiography in constrictive pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994. 23:154–162.

16. Sun JP, Abdalla IA, Yang XS, et al. Respiratory variation of mitral and pulmonary venous Doppler flow velocities in constrictive pericarditis before and after pericardiectomy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2001. 14:1119–1126.

17. Ha JW, Oh JK, Ommen SR, Ling LH, Tajik AJ. Diagnostic value of mitral annular velocity for constrictive pericarditis in the absence of respiratory variation in mitral inflow velocity. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002. 15:1468–1471.

18. Sohn DW, Kim YJ, Kim HS, Kim KB, Park YB, Choi YS. Unique features of early diastolic mitral annulus velocity in constrictive pericarditis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004. 17:222–226.

19. Oh JK, Tajik AJ, Appleton CP, Hatle LK, Nishimura RA, Seward JB. Preload reduction to unmask the characteristic Doppler features of constrictive pericarditis: a new observation. Circulation. 1997. 95:796–799.

20. Garcia MJ, Rodriguez L, Ares M, Griffin BP, Thomas JD, Klein AL. Differentiation of constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy: assessment of left ventricular diastolic velocities in longitudinal axis by Doppler tissue imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996. 27:108–114.

21. Reuss CS, Wilansky SM, Lester SJ, et al. Using mitral 'annulus reversus' to diagnose constrictive pericarditis. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009. 10:372–375.

22. Choi JH, Choi JO, Ryu DR, et al. Mitral and tricuspid annular velocities in constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy: correlation with pericardial thickness on computed tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011. 4:567–575.

23. Ha JW, Oh JK, Ling LH, Nishimura RA, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. Annulus paradoxus: transmitral flow velocity to mitral annular velocity ratio is in versely proportional to pulmonary capillary wedge pressure inpatients with constrictive pericarditis. Circulation. 2001. 104:976–978.

24. Ling LH, Oh JK, Tei C, et al. Pericardial thickness measured with transesophageal echocardiography: feasibility and potential clinical usefulness. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997. 29:1317–1323.

25. Pandian NG, Skorton DJ, Kieso RA, Kerber RE. Diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis by two-dimensional echocardiography: studies in a new experimental model and in patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1984. 4:1164–1173.

26. Candell-Riera J, García del Castillo H, Permanyer-Miralda G, Soler-Soler J. Echocardiographic features of the interventricular septum in chronic constrictive pericarditis. Circulation. 1978. 57:1154–1158.

27. Chowdhury UK, Subramaniam GK, Kumar AS, et al. Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: a clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic evaluation of two surgical techniques. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006. 81:522–529.

28. DeValeria PA, Baumgartner WA, Casale AS, et al. Current indications, risks, and outcome after pericardiectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991. 52:219–224.

29. Haley JH, Tajik AJ, Danielson GK, Schaff HV, Mulvagh SL, Oh JK. Transient constrictive pericarditis: causes and natural history. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004. 43:271–275.

30. Feng D, Glockner J, Kim K, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging pericardial late gadolinium enhancement and elevated inflammatory markers can predict the reversibility of constrictive pericarditis after antiinflammatory medical therapy: a pilot study. Circulation. 2011. 124:1830–1837.

31. Bush CA, Stang JM, Wooley CF, Kilman JW. Occult constrictive pericardial disease: diagnosis by rapid volume expansion and correction by pericardiectomy. Circulation. 1977. 56:924–930.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download