Abstract

Coronary artery disease is the most important cause of mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematous (SLE). After stenting for coronary artery disease in SLE patients similar to non-SLE patients, the risk of stent thrombosis is always present. Although there are reports of stent thrombosis in SLE patients, very late recurrent stent thrombosis is rare. We experienced a case of very late recurrent stent thrombosis (4 times) in a patient with SLE.

Systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that can damage various organs secondary to autoantibodies. In particular, coronary atherosclerosis can be caused by involvement of antibodies on the coronary artery, and exists in up to 40% of patients with SLE.1) Thus, coronary atherosclerosis occurs prematurely2) and is related to acute coronary syndrome in young patients with SLE.3)4) For the treatment of coronary artery disease in patients with SLE, coronary artery stent insertion is usually considered to be the optimal treatment, as in non-SLE patients. However, several reports showed that coronary artery stenting in SLE patients is related to poor prognosis due to in-stent restenosis or thrombosis.5-7) However, there is no reported case of repeated stent thrombosis in a patient with SLE. We herewith present a rare case of recurrent, very late stent thrombosis (4 times) after drug eluting stents (DES) implantation in a SLE patient.

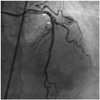

A 52-year-old female with a history of SLE who had underdone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), initially presented to the emergency department a 2 hour history of continuous chest pain in the substernal area. For twenty years, she has been treated for lupus and its pulmonologic and renal complications at other hospitals. Two years ago, she underwent transarterial embolization of her bronchial artery due to hemoptysis. Two month later, she visited the cardiovascular department of this hospital with severe chest pain, and underwent PCI in the mid left anterior descending artery (LAD), and its diagonal branch with a 3.0×32 mm Taxus® Express2 paclitaxel-eluting stent (Boston Scientific Corp., Natick, MA, USA) for the mid LAD and a 2.5×24 mm Taxus® stent for the diagonal branch. Since the PCI, she has been taking aspirin, 100 mg; clopidogrel, 75 mg and cilostazol, 100 mg for coronary artery disease treatment and prednisolone, 5 mg and hydroxyquinolone for lupus treatment. On visiting the emergency department, her electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ST-segment elevation in V1-V4. Her laboratory data revealed 206 ng/mL of creatine phospho kinase, 17.8 ng/mL of creatine kinase-MB level and 1.69 ng/mL of troponin-I level. She was diagnosed with an anterior-septal ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and taken immediately to the catheterization laboratory. Coronary angiography (CAG) revealed total occlusion over the previous stent site of the mid LAD and the diagonal branch (Fig. 1A), therefore we performed balloon angioplasty to treat the total occluded lesion of the mid LAD. However, we could not perform any intervention for the diagonal branch due to wiring failure. The final angiogram after balloon angioplasty showed thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) grade III flow of the LAD and moderate stenosis of the proximal LAD (Fig. 1B). The patient was discharged without complications.

However, five weeks later, the patient presented to our emergency department with severe chest pain associated with ST elevation on ECG on arrival. Under suspicion of recurrent stent thrombosis, we performed emergency CAG, which showed thrombotic re-occlusion of the LAD stent with TIMI grade 0 flow. We elected to perform balloon angioplasty and deployed a 3.0×18 mm XIENCE V stent (Abbott vascular, Redwood City, CA, USA) to cover the progressed lesion of the proximal LAD, overlapping the proximal part of the previous stent. Her final angiogram demonstrated a TIMI grade III flow of the LAD (Fig. 2). Subsequently, we checked her platelet function using a PFA 100® system (Dade International, Miami, FL, USA). The measured closure time with epinephrine cartridges was 178 seconds (normal range: 192-78), and with ADP cartridges, it was 92 seconds (normal range: 146-58). The patient recovered without cardiac complications. She was discharged five days later with aspirin (100 mg daily), clopidogrel (75 mg daily) and cilostazole (50 mg, twice a day).

The patient visited our emergency department again after 8 weeks with recurrent chest pain associated with ST elevation on her ECG. An emergency coronary angiogram showed thrombotic re-occlusion of the mid portion of the previous LAD stent, similar to the previous event. We then performed balloon angioplasty with a 3.0×15 mm VOYAGER(TM) NC balloon (Abbott vascular, Redwood City, CA, USA), which successfully established TMI grade III flow. Subsequent laboratory data on SLE disease and coagulation states revealed her stable lupus and no coagulation abnormalities: lupus anticoagulant: negative, Anti cardiolipin Ab IgG/M: negative, Anti Phospholipid Ab IgG: 3.8 GPLunit/mL, Anti Phospholipid IgM: 0.7 MPLunit/mL, C3: 119 ng/dL {Normal (N): 160-86}, C4: 20.34 ng/dL (N: 17-45), Homocystein 6 umol/L (N: 5-15), Protein C activity: 110% (N: 70-130), Protein S activity: 65% (N: 55-123). She was discharged with a double dose of aspirin (200 mg daily) and clopidogrel (150 mg daily).

Five months after her last discharge, she visited our emergency department again with recurrent chest pain. The ECG again showed ST elevation of the precordial lead and CAG showed stent thrombosis, similar to the previous event. However, after balloon angioplasty, multiple thrombi in the distal part of the stent and disease progression at the edge of stent were shown (Fig. 3A). We therefore performed an intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), which showed eccentric plaque with thrombi in the stent and isoechoic plaque with significant stenosis at the distal edge of the stent (Fig. 3B and C). After performing the IVUS, we deployed a 3.0×30 mm Endeavor® Resolute stent (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for this lesion, overlapping the previous stent. Final angiographic findings showed good distal flow (Fig. 3D). On discharge, we increased her dosage of aspirin to 300 mg daily.

Coronary artery disease is now considered to be the most important cause of mortality in patients with SLE.8) Roman et al.2) reported that atherosclerosis occurs prematurely in patients with SLE and is independent of traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease. In Korea, Moon et al.9) reported a case of premature coronary atherosclerosis associated with SLE.

Revascularization for the treatment of coronary artery disease in patients with SLE, especially with coronary stenting, may be the most important treatment modality. However, coronary stenting can also be challenging for SLE patients, regardless of stent type. Bare metal stents are related to high rate of repeated revascularization, and DES can cause stent thrombosis. One study analyzed 25 SLE patients who underwent PCI showed that the long-term (40 month) adverse event rate was 28% in these unselected patients.5) In their case study, Lee and Chan6) raised the question of whether DES implantation was optimal therapy for SLE patients.

Our patient experienced rapid progression of coronary artery disease and recurrent, very late stent thrombosis against the background of DES implantation. For this patient, it was not simple to determine treatment modalities, such as stent type, or medications, because of her complex medical histories. During the first event, although disease progression at the upper part of the stent was found, we only performed balloon angioplasty because additional stent implantation may cause further events. When the second attack occurred, however, we found that this patient was unresponsive to aspirin, but we could not increase her dose of aspirin or clopidogrel further, because of her pulmonary bleeding history and multiple medications.

The mechanisms underlying stent thrombosis in SLE patients remain unclear. In the literature, there are several reports that explained some possible mechanisms. Oliver and Hollman7) reported a patient with SLE who presented with late in-stent thrombosis while on clopidogrel and aspirin. This patient showed high homocystein level, and the authors explained that hyperhomocysteima could be associated with late in-stent thrombosis. Although not addressing cases of SLE, Muir et al.10) reported that circulating lupus anticoagulants could be associated with recurrent stent thrombosis, and Su et al.11) presented a patient with acute stent thrombosis related to antiphospholipid syndrome. However, our experienced stable lupus state and did not present with coagulation abnormality. Instead of a hypercoagulation state, resistance to antiplatelet therapy was explained as a mechanism of stent thrombosis.12) In this case, the platelet function test to verify the patient's response to aspirin was within the normal range, which means non-responsiveness to aspirin, and could be a reason to increase the aspirin dosage up to 300 mg daily. Although we could not check the responsiveness of clopidogrel, we increased the dosage of clopidogrel because we suspected non-response of the clopidogrel. Regardless of SLE, the mechanism of very late stent thrombosis can be caused by stent malapposition and disease progression with neointimal rupture.13) Although the IVUS finding showed disease progression of distal part of stent, there was no evidence of stent malapposition or plaque rupture at the thrombotic obstructed lesion.

In conclusion, although the prevalence of SLE is low, coronary artery disease is one of the most important causes of death in patients with SLE. PCI is the most commonly used method to treat coronary artery disease in these patients. However, particularly in cases of DES implantation, patients with SLE have to be considered regarding situations that can cause stent thrombosis, such as hyperactivity of lupus state, the hypercoagulation state and resistance to antiplatelet therapy. Eventually, we decided to implant two more DES and prescribed antiplatelet medications at full dose. However, we still need to perform close observation regarding stent thrombosis and clinical events such as bleeding.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The first event of stent thrombosis. A: coronary angiogram showing total occlusion over the previous stent site of the mid LAD and the diagonal branch. B: coronary angiography after balloon angioplasty showing thrombolysis in myocardial infarction grade III flow of the LAD and moderate stenosis of the proximal LAD. LAD: left anterior descending artery.

Fig. 2

The second event of stent thrombosis. Coronary angiogram is showing good distal flow (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction III) after stent implantation in proximal left anterior descending artery with overlapping proximal part of the previous stent (arrow).

Fig. 3

The fourth event of stent thrombosis. A: coronary angiogram after balloon angioplasty showing multiple thrombi in the distal part of the stent and disease progression at the edge of stent. B and C: intravascular ultrasound finding is showing eccentric plaque with thrombi in the stent (B, arrow), and isoechoic plaque with significant stenosis at the distal edge of the stent (C, arrow). D: coronary angiogram showing good distal flow (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction III) after implantation of the stent in the distal part of the previous stent, overlapping the distal part of previous stent.

References

1. Haider YS, Roberts WC. Coronary arterial disease in systemic lupus erythematous: quantification of degree of narrowing in 22 necropsy patients (21 women) aged 16 to 37 years. Am J Med. 1981. 70:775–781.

2. Roman MJ, Shanker BA, Davis A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003. 349:2399–2406.

3. Mehta PK, Samady H, Vassiliades TA, Book WM. Acute coronary syndrome as a first presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in a teenager: revascularization by hybrid coronary artery bypass graft surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention: case report. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008. 29:957–961.

4. Kassaian SE, Goodarzynejad H, Darabian S, Basiri Z. Myocardial infarction secondary to premature coronary artery disease as the initial major manifestation of systemic lupus erythematous. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2008. 19:152–154.

5. Lee CH, Chong E, Low A, Lim J, Lme YT, Tan HC. Long-term follow-up after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with systemic lupus erythematous. Int J Cardiol. 2008. 126:430–432.

6. Lee CH, Chan MY. Dilemma of drug-eluting stent implantation in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Cardiol. 2007. 114:e107–e108.

7. Olivier AC, Hollman JL. Late in-stent thrombosis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and hyperhomocysteinemia while on clopidogrel and aspirin. J Invasive Cardiol. 2006. 18:E185–E187.

8. Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 10-year period: a comparison of early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003. 82:299–308.

9. Moon YG, Kim YJ, Jeon DS, et al. A case of premature coronary atherosclerosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Korean Circ J. 1995. 25:691–697.

10. Muir DF, Stevens A, Napier-Hemy RO, Fath-Ordoubadi F, Curzen N. Recurrent stent thrombosis associated with lupus anticoagulant due to renal cell carcinoma. Int J Cardiovasc Intervent. 2003. 5:44–46.

11. Su HM, Lee KT, Chu CS, Sheu SH, Lai WT. Acute thrombosis after elective direct intracoronary stenting in primary antiphospholipid syndrome: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2003. 19:177–182.

12. Lee KH, Lee SW, Lee JW, et al. The significance of clopidogrel low-responsiveness on stent thrombosis and cardiac death assessed by the verifynow p(2)y(12) assay in patients with acute coronary syndrome within 6 months after drug-eluting stent implantation. Korean Circ J. 2009. 39:512–518.

13. Lee CW, Kang SJ, Park DW, et al. Intravascular ultrasound findings in patients with very late stent thrombosis after either drug-eluting or bare-metal stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010. 55:1936–1942.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download