Abstract

Background and Objectives

Little evidence is available on the optimal antithrombotic therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). We investigated the outcomes of antithrombotic treatment strategies in AF patients who underwent PCI.

Subjects and Methods

Three hundred sixty-two patients (68.0% men, mean age: 68.3±7.8 years) with AF and who had undergone PCI with stent implantation between 2005 and 2007 were enrolled. The clinical, demographic and procedural characteristics were reviewed and the stroke risk factors as well as antithrombotic regimens were analyzed.

Results

The accompanying comorbidities were as follows: hypertension (59.4%), diabetes (37.3%) and congestive heart failure (16.6%). The average number of stroke risk factors was 1.6. At the time of discharge after PCI, warfarin was prescribed for 84 patients (23.2%). Cilostazol was used in addition to dual antiplatelet therapy in 35% of the patients who did not receive warfarin. The mean follow-up period was 615±385 days. The incidences of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), stroke and major bleeding were 11.3%, 3.6% and 4.1%, respectively. By Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, warfarin treatment was not associated with a lower risk of MACE (p=0.886), but it was associated with an increased risk of major bleeding (p=0.002).

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and it is associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events. Oral anticoagulation with warfarin should be considered for the patients with AF and who have multiple risk factors to prevent ischemic stroke.1) Several meta-analyses have shown that warfarin treatment in patients with nonvalvular AF is associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke and cardiovascular events, but it is also associated with an elevated risk of major hemorrhage.2)3)

Antithrombotic strategies become problematic when AF patients who require warfarin subsequently have to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent implantation. The 2006 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology guidelines on AF management1) suggest that the maintenance regimen should consist of a combination of clopidogrel plus warfarin for 9 to 12 months, followed by warfarin monotherapy in the absence of a coronary event. However, others have suggested different management guidelines4) and none of the issued guidelines have been based on prospective randomized trials.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether the use of oral anticoagulants is associated with better clinical outcomes in Korean AF patients who undergo PCI with stenting.

We performed this retrospective analysis using the information obtained from the registry databases at five cardiovascular centers. The study subjects were AF patients who underwent PCI with stent implantation between January 2005 and December 2007. All patients with a previous diagnosis of paroxysmal, persistent or permanent AF were enrolled, and those who developed new onset AF at the time of admission for PCI were also included.

We reviewed the procedural, patient, clinical and demographic characteristics. The stroke risk factors and the antithrombotic therapy administered on admission and at discharge were recorded. The stroke risks were assessed by using the CHADS2 scoring system (1 point each is assigned for cardiac failure, hypertension, an age over 75 years and diabetes while 2 points are assigned for a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack).5) The left ventricular ejection fraction was recorded, as was measured by transthoracic echocardiography using the modified Simpson's method.

The individual patient management decisions were made by the attending cardiologists. All coronary procedures were decided on by the attending interventional cardiologists, as were the strategies for oral anticoagulation and antiplatelet drugs at discharge, which was based on the type of AF, the st-roke risk factors, the revascularization procedures and the types of implanted stents.

Patients were followed up at 1 to 2 month intervals in an outpatient clinic setting. The patients who were administered warfarin were monitored for prothrombin time. The warfarin doses were adjusted to maintain an international normalized ratio (INR) target range of 2.0 to 3.0. We collected total INR data for each patient and determined whether they were above, below or within the therapeutic range (2.0-3.0). The percentage of each range was averaged in all patients. Information was obtained by reviewing the medical records and by conducting telephone interviews with the patients or the patients' families. Death was determined from the family members or from the hospital discharge summaries.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of each center, and written informed consent for the procedure was obtained from all patients.

The primary end point was defined as the occurrence of major adverse cardiac events (MACEs), which included death, myocardial infarction and target vessel revascularization. The secondary safety end points were defined as major adverse events (MAEs), which included any MACE, a bleeding episode or stroke during follow-up. Myocardial infarction was diagnosed if a typical rise and fall in cardiac biochemical markers {troponin or creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB)} was accompanied by at least one of the following: symptoms of ischemia, electrocardiography (ECG) changes indicative of new ischemia (new ST-T changes or new left bundle branch block), the development of pathological ECG Q waves, imaging evidence of a new loss of viable myocardium or a new regional wall motion abnormality. Stent thrombosis was defined as symptoms suggestive of an acute coronary syndrome and angiographic confirmation of thrombosis.

Major bleeding was defined as a decrease in hemoglobin of 2 g/dL or more over a 24-hour period, the need for a transfusion of two or more units of packed red blood cells, bleeding leading to death and bleeding at the following critical sites: intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, pericardial, intra-articular, retroperitoneal or intramuscular bleeding with compartment syndrome. Minor bleeding was defined as acute clinically overt bleeding that did not meet the criteria for major bleeding, such as nasal or gastrointestinal bleeding, hematuria, ecchymosis or hemoptysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The continuous variables with normal distributions were expressed as means±SDs and these were compared using an unpaired Student's t-test and nonparametric variables were compared using a Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared with a Fisher's exact test or the χ2 test, as appropriate. All comparisons were two-sided, and p<0.05 were regarded as being statistically significant.

Event-free survivals were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and they were compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazard model (the 'Enter method'). Variables that showed a p<0.15 on the univariate analysis or that could influence the clinical outcomes regardless of the univariate p were entered in the multivariate analysis. Variables included in the multivariate analysis were age, type of AF, hypertension, diabetes, the previous use of clopidogrel and/or warfarin, and the total number of stents.

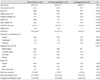

We reviewed the records of 362 patients (68.0% men, mean age: 68.3±7.8 years). The characteristics of the study population in relation to the use of oral anticoagulants at discharge are shown in Table 1. The anticoagulation group was slightly younger than the non-anticoagulation group. Of the 362 patients, 150 (41.4%) had paroxysmal AF. In total, 45.5% of patients had a CHADS2 score of ≥2. The indications for PCI were chronic stable angina (43%) and acute coronary syndrome (57%). Drug-eluting stents were used in most cases and a Cypher stent (Cordis Corporation, Miami, FL, USA) was used more frequently than a Taxus stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA). Two or more stents were implanted in 43.8% of the patients.

The antithrombotic regimens used at discharge are summarized in Table 2. Anticoagulation with warfarin was used in 23% of the patients. Cilostazol was used in 35% of the patients who did not receive warfarin. None of the patients received monotherapy at discharge. In the anticoagulation group, 17% of the patients discontinued warfarin within 1 year due to side effects or poor compliance. Aspirin, clopidogrel and cilostazol were usually administered at least 1 year after the procedure regardless of the type of stent used. Patients on oral anticoagulation therapy had INR values in the therapeutic range (2.0-3.0) 52% of the time; 27% of the time they were below and 21% of the time, they were above 3.0.

Clinical follow-up records were analyzed for the patients (average length of follow-up: 615±385 days). Clinical events during follow-up and according to the use of oral anticoagulants are summarized in Table 3. The use of warfarin did not affect the MACEs or MAEs by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (Log-Rank test) (Fig. 1). On the Cox regression analysis, diabetes was an independent predictor of both MACEs {hazard ratio (HR)=1.775; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.142 to 2.760} and MAEs (HR=4.543; 95% CI: 2.260 to 9.131), but anticoagulation with warfarin was not (HR=0.943 with 95% CI, 0.556 to 1.593 and HR=0.755 with 95% CI, 0.346 to 1.649, respectively). In addition, multivariate analysis for major ble-eding was performed. Independent predictors for major ble-eding were total stent number (HR=2.020 with CI, 1.045 to 3.943) and warfarin use (HR=7.564 with CI, 2.051 to 27.895).

The aim of this study was to investigate whether oral anticoagulation adds benefit to the antiplatelet therapy in Asian AF patients who underwent PCI with stent implantation. In this study, the occurrence of clinical events was found to be independent of warfarin use at discharge. Ruiz-Nodar et al.6) reported that warfarin could reduce MACEs primarily by reducing target vessel failure and death in a study that focused on a similar group of patients. In that study, the commonly used regimen for those who do not receive warfarin was a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel. None of the patients received cilostazol as an antithrombotic agent. In our study, cilostazol was used in 35% of the non-anticoagulation group. Recent studies have shown that adding cilostazol to aspirin and clopidogrel can reduce the incidence of target lesion revascularization in patients who have undergone PCI with drug-eluting stents.7) Women, diabetics and those having multivessel disease or a long stent length are more likely to benefit from triple antiplatelet therapy.8)9) In our study's non-anticoagulation group, the mean total stent length was 37.1 mm and 35.6% of the patients had diabetes; these patients might have derived some benefit from a triple antiplatelet regimen.

The incidence of ischemic stroke in the non-anticoagulation group was not significantly different from that in the anticoagulation group. ACTIVE-W study showed that warfarin is superior to clopidogrel plus aspirin for the prevention of vascular events in patients with AF.10) Dose adjustment and close monitoring of the prothrombin time are prerequisites for successful anticoagulation therapy. In a subanalysis of the ACTIVE-W study, inadequate control of the INR did not provide benefit of oral anticoagulation over dual antiplatelet therapy.11) In our study, patients in the oral anticoagulation group had an INR value within the therapeutic range 52% of the time, which is low compared with 64% in the ACTIVE-W study. This might compromise the benefit of anticoagulation therapy.

The incidence of major bleeding in the oral anticoagulation group was significantly higher than that in the non-anticoagulation group. A combination of antiplatelet and anticoagulation drugs usually carries a greater risk of bleeding than that of each drug alone.12) In addition, Asians are more vulnerable to major bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage than are non-Asians in the context of warfarin use.13)14) The warfarin dose requirements are affected by polymorphisms in P450 cytochrome CYP2C9,15) and by variants in the gene expressing vitamin K epoxide reductase complex 1 (VKORC1), which is the target enzyme of warfarin.16) Therefore, Asians may require a lower warfarin dosage and this is probably due to the differences in the allelic frequencies of the CYP2C9 and VKORC1 variants.17)

This study has several limitations. First, given the low rate of bleeding events, the power of the study to detect significant differences in MACEs was limited. Second, the follow-up periods varied widely because of the retrospective design of the study. Third, the interval of INR measurement for patients on the oral anticoagulation group was also variable in each patient.

In conclusion, oral anticoagulation therapy after PCI may increase hemorrhagic events in Korean AF patients. Warfarin should be administered more carefully in these patients.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Kaplan-Meier survival curves in relation to the use of anticoagulants drugs at discharge. A: major adverse cardiovascular events, p=0.886. B: major adverse events, p=0.637. Solid and dotted line indicates no anticoagulation use and anticoagulation use at discharge, respectively.

References

1. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation-executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006. 48:854–906.

2. van Walraven C, Hart RG, Singer DE, et al. Oral anticoagulants vs aspirin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: an individual patient meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002. 288:2441–2448.

3. Aguilar MI, Hart R, Pearce LA. Oral anticoagulants versus antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007. CD006186.

4. Lip GY, Karpha M. Anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy use in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the need for consensus and a management guideline. Chest. 2006. 130:1823–1827.

5. Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001. 285:2864–2870.

6. Ruiz-Nodar JM, Marin F, Hurtado JA, et al. Anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy use in 426 patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and stent implantation implications for bleeding risk and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008. 51:818–825.

7. Lee SW, Park SW, Kim YH, et al. Comparison of triple versus dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation (from the DECLARE-Long trial). Am J Cardiol. 2007. 100:1103–1108.

8. Han Y, Li Y, Wang S, et al. Cilostazol in addition to aspirin and clopidogrel improves long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a randomized, controlled study. Am Heart J. 2009. 157:733–739.

9. Yang TH, Kim DI, Kim JY, et al. Comparison of triple anti-platelet therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel, and cilostazol) and double anti-platelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) on platelet aggregation in type 2 diabetic patients undergoing drug-eluting stent implantation. Korean Circ J. 2009. 39:462–466.

10. Connolly S, Pogue J, Hart R, et al. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006. 367:1903–1912.

11. Connolly SJ, Pogue J, Eikelboom J, et al. Benefit of oral anticoagulant over antiplatelet therapy in atrial fibrillation depends on the quality of international normalized ratio control achieved by centers and countries as measured by time in therapeutic range. Circulation. 2008. 118:2029–2037.

12. Sorensen R, Hansen ML, Abildstrom SZ, et al. Risk of bleeding in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with different combinations of aspirin, clopidogrel, and vitamin K antagonists in Denmark: a retrospective analysis of nationwide registry data. Lancet. 2009. 374:1967–1974.

13. Shen AY, Yao JF, Brar SS, Jorgensen MB, Chen W. Racial/ethnic differences in the risk of intracranial hemorrhage among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. 50:309–315.

14. Suzuki S, Yamashita T, Kato T, et al. Incidence of major bleeding complication of warfarin therapy in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ J. 2007. 71:761–765.

15. Higashi MK, Veenstra DL, Kondo LM, et al. Association between CYP2C9 genetic variants and anticoagulation-related outcomes during warfarin therapy. JAMA. 2002. 287:1690–1698.

16. Li T, Lange LA, Li X, et al. Polymorphisms in the VKORC1 gene are strongly associated with warfarin dosage requirements in patients receiving anticoagulation. J Med Genet. 2006. 43:740–744.

17. Rieder MJ, Reiner AP, Gage BF, et al. Effect of VKORC1 haplotypes on transcriptional regulation and warfarin dose. N Engl J Med. 2005. 352:2285–2293.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download