Abstract

Stent thrombosis is a fatal complication in patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, and discontinuation of anti-platelet agent is a major risk factor of stent thrombosis. We report a rare case of very late stent thrombosis (VLST) following discontinuation of anti-platelet agents in a patient who experienced acute myocardial infarction and essential thrombocytosis. She had undergone implantation of a drug eluting stent (DES) and a bare metal stent (BMS) two and half years prior to her presentation. VLST developed in DES, not in BMS, following interruption of anti-platelet therapy.

Drug-eluting coronary artery stents (DES) are currently being widely used. The advantage of DES is that it markedly reduces the rate of restenosis and the need for repeat revascularization.1-3) Despite these promising advances, stent thrombosis appears to occur more frequently with DES. Therefore, in patients with implanted DES, longer duration of anti-platelet therapy is needed, and they should maintain anti-platelet therapy even when they undergo endoscopic procedures.

We report a case of very late stent thrombosis (VLST) that occurred only in DES, not in bare metal stent (BMS), following discontinuation of anti-platelet therapy, in a patient presented with essential thrombocytosis (ET) and acute myocardial infarction.

A 65-year-old female was transferred to the emergency department at our hospital, complaining of stabbing chest pain that radiated to her left arm and back that persisted over four hours. She had a history of acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction and underwent BMS implantation (4.0×25 mm and 4.0×13 mm Coroflex Blue Stent) for the proximal and middle right coronary artery (RCA), respectively, as well as DES (a 3.0×18 mm Cypher stent) implantation for the distal left circumflex artery (LCX) two-and-half years previously (Fig. 1). She had since commenced on dual anti-platelet therapy (aspirin 100 mg, clopidogrel 75 mg daily). Coronary angiography (CAG) performed after eight months showed no evidence of restenosis. She ceased taking aspirin and clopidogrel for an endoscopic procedure two days before her latest presentation.

On examination, she appeared to be in acute distress. Her blood pressure was 110/60 mmHg, her heart rate was 60 beat per minute, her respiratory rate was 16/min, and her temperature was 37℃. Her oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. Pertinent findings on chest examination included fine crackles heard at the bases. Her cardiovascular examination revealed normal first and second heart sounds, with no evidence of jugular venous distention, murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The remainder of her physical examination was unremarkable.

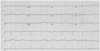

Electrocardiogram showed ST-segment elevation in lead II, III and aVF (Fig. 2), and cardiac enzymes were within the normal limits (creatine kinase-MB 3.9 U/L, troponin-I 0.04 ng/mL). Complete blood count (CBC) results were as follows: hemoglobin level was 17.5 g/dL, hematocrit was 52.8%, and platelet count was 1,168×103/mm3. She underwent emergent CAG, which demonstrated thrombotic total occlusion of the distal LCX secondary to stent thrombosis, but the RCA stent was patent (Fig. 3). Therefore, we performed emergent PCI using 3.0 mm balloon for the distal LCX, and applied intracoronary abciximab (Clotinab®) for thrombi visualization. Post-PCI CAG showed no residual stenosis and relatively good distal flow (Fig. 4).

During the patient's hospitalization, we performed bone marrow biopsy to further evaluate the cause of thrombocytosis, which confirmed ET. She was subsequently managed with repeated phlebotomy and platleletapharesis to reduce the level of hematocrit and platelet count. In addition, she was commenced with anagrelide and hydroxyurea, but her CBC profile fluctuated during hospital stay. She subsequently made an uneventful recovery, and was discharged with continuous triple anti-platelet agent therapy of aspirin, clopidogrel and cilostazol. After discharge, the patient has been followed up at the outpatient cardiology and hematology clinics without experiencing further symptoms.

We report this case to raise the awareness of coronary stent thrombosis associated with anti-platelet therapy discontinuation. This case is very interesting in that the difference between DES and BMS, or essential thrombosis which might contribute to the development of VLST.

VLST is defined as stent thrombosis presented one year after PCI. Recently, some concerns have been raised that late or VLST tends to be more common in DES than BMS.4-8) In this case, VLST has occurred in DES only, but not in a BMS. Similarly, Kim et al.9) reported a case of VLST solely in DES, not in BMS. Some clinical data demonstrated that neointimal coverage after DES implantation was later than that in BMS.10)11) Therefore, we hypothesized that the uncovered strut of DES persisted and stent thrombosis might have occurred under special circumstances, such as discontinuation of anti-platelet agents.

The role of anti-platelet therapy discontinuation in early stent thrombosis is well-recognized,12-14) but its role in LST and VLST remains unclear. However, current guidelines on anti-platelet and anticoagulant therapy in endoscopic procedures15)16) recommend continuation of aspirin regardless of bleeding risk, and continuation of clopidogrel in low risk procedures. On the contrary, the guidelines recommended stopping clopidogrel 7 days before a high risk procedure if the patient is at least 12 months post-DES insertion, and at least 1 month post-BMS insertion. As such, our patient would have benefited from uninterrupted aspirin administration.

ET is a myeloproliferative disorder characterized by clonal proliferation of megakaryocytes, resulting in thrombocytosis. Thrombosis and hemorrhage are typical complications in patients with ET. Tefferi et al.17) reported that major thrombotic complications, such as cerebral ischemic attack and acute coronary syndrome, occurred in 7% of ET patients. Cases of acute coronary syndrome with ET were reported by some authors,18-20) but our experience of VLST associated with ET was unique.

In conclusion, ET and discontinuation of antiplatelet agent might have contributed to VLST of the DES in our patient. Discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy, even after one year in patients who have undergone DES placement, requires extreme caution, particularly in patients with thrombosis and acute coronary syndrome.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Patient underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the right coronary artery (RCA) due to inferior ST elevation myocardial infarction two and a half years ago. Initial coronary angiogram revealed critical stenosis in middle RCA (95%) and distal left circumflex artery (LCX) (80%) (A and C). We deployed bare metal stent in the proximal and middle RCA (B), and drug-eluting stent in the distal LCX by staged PCI (D).

References

1. Colombo A, Drzewiecki J, Banning A, et al. Randomized study to as-sess the effectiveness of slow- and moderate-release polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting stents for coronary artery lesions. Circulation. 2003. 108:788–794.

2. Serruys PW, Degertekin M, Tanabe K, et al. Intravascular ultrasound findings in the multicenter, randomized, double-blind RAVEL (RAndomized study with the sirolimus-eluting VElocity balloon-expandable stent in the treatment of patients with de novo native coronary artery Lesions) trial. Circulation. 2002. 106:798–803.

3. Zhang F, Ge J, Qian J, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stents in real-world patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Int Heart J. 2007. 48:303–311.

4. Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K, et al. Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet. 2007. 369:667–678.

5. Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Pache J, et al. Analysis of 14 trials comparing sirolimus-eluting stents with bare-metal stents. N Engl J Med. 2007. 356:1030–1039.

6. Pinto Slottow TL, Steinberg DH, Roy PK, et al. Observations and outcomes of definite and probable drug-eluting stent thrombosis seen at a single hospital in a four-year period. Am J Cardiol. 2008. 102:298–303.

7. Spaulding C, Daemen J, Boersma E, Cuttlip DE, Serruys PW. A pooled analysis of data comparing sirolimus-eluting stents with bare-metal stents. N Engl J Med. 2007. 356:989–997.

8. Stone GW, Moses JW, Ellis SG, et al. Safety and efficacy of sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents. N Engl J Med. 2007. 356:998–1008.

9. Kim SS, Jeong MH, Sim DS, et al. Very late thrombosis of a drug-eluting stent after discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in a patient treated with both drug-eluting and bare-metal stents. Korean Circ J. 2009. 39:205–208.

10. Awata M, Kotani J, Uematsu M, et al. Serial angioscopic evidence of incomplete neointimal coverage after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: comparison with bare-metal stents. Circulation. 2007. 116:910–916.

11. Takano M, Yamamoto M, Xie Y, et al. Serial long-term evaluation of neointimal stent coverage and thrombus after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation by use of coronary angioscopy. Heart. 2007. 93:1353–1356.

12. Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2005. 293:2126–2130.

13. Kuchulakanti PK, Chu WW, Torguson R, et al. Correlates and long-term outcomes of angiographically proven stent thrombosis with sirolimus-and paclitaxel-eluting stents. Circulation. 2006. 113:1108–1113.

14. Park DW, Park SW, Park KH, et al. Frequency of and risk factors for stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation during long-term follow-up. Am J Cardiol. 2006. 98:352–356.

15. Veitch AM, Baglin TP, Gershlick AH, et al. Guidelines for the management of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gut. 2008. 57:1322–1329.

16. Zuckerman MJ, Hirota WK, Adler DG, et al. ASGE guideline: the management of low-molecular-weight heparin and nonaspirin antiplatelet agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005. 61:189–194.

17. Tefferi A, Fonseca R, Pereira DL, Hoagland HC. A long-term retrospective study of young women with essential thrombocythemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001. 76:22–28.

18. Turgut T, Harjai KJ, Edupuganti R, et al. Acute coronary occlusion and in-stent thrombosis in a patient with essential thrombocythemia. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1998. 45:428–433.

19. Watanabe T, Fujinaga H, Ikeda Y, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in a patient with essential thrombocythemia who underwent successful stenting: a case report. Angiology. 2005. 56:771–774.

20. Kumagai N, Mitsutake R, Miura S, et al. Acute coronary syndrome associated with essential thrombocythemia. J Cardiol. 2009. 54:485–489.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download