Abstract

Background and Objectives

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cryptogenic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) due to paradoxical embolism, and in the pathogenesis of migraine. This paper reports the intermediate and long-term results of transcatheter closure of PFO associated with cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), TIAs and migraine, using the Amplatzer PFO occluder. This paper also reports a case of pulmonary embolism which developed in one patient after PFO closure.

Subjects and Methods

From January 2003 to May 2010, 16 patients with PFO (seven males and nine females) with a history of at least one episode of cryptogenic stroke/TIA, CVA, or migraine and who underwent percutaneous transcatheter closure of PFO using the Amplatzer occluder. All the procedures were performed under general anesthesia and were assisted by transesophageal echocardiography.

Results

The device was implanted without any significant complications in all the patients, and the PFOs were effectively closed. At an average follow-up period of 54 months, the 15 patients with TIA/CVA had no recurrence of any thromboembolic event. The symptoms in one patient with migraine subsided after occlusion of the PFO. In this study, pulmonary embolism occurred five months after PFO closure in one patient, but the cause of pulmonary embolism was not identified. However, it is believed that the pulmonary embolism occurred without stroke recurrence because occlusion of the PFO was performed when the patient had a stroke event.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that according to the intermediate and long-term follow-up results, transcatheter PFO closure is an effective and safe therapeutic modality in the prevention of thromboembolic events, especially in the patients with cryptogenic stroke/TIA, and PFO closure is helpful in the treatment of migraine. However, this study involved a small number of patients and also the follow-up period was not long enough. Hence, randomized, controlled trials are necessary to determine if this approach is preferable to medical therapy for the prevention of recurrent stroke or as primary treatment for patients with migraine headache.

The etiology of ischemic stroke remains unknown in upto 40% of patients, despite an extensive diagnostic evaluation, and is referred to as cryptogenic.1) Patients with cryptogenic stroke have a higher prevalence of patent foramen ovale (PFO) than patients with stroke of determined cause.2) The relation-ship between paradoxical (right-to-left) embolism through a PFO and stroke remains controversial because of variability in the reported stroke risk in patients with PFOs.3) A high risk assessment study with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) found a PFO in 25.6% of healthy subjects.4) Excess atrial septal tissue in the region of the fossa ovalis causes increased movement of the septum during respiration. This finding is classified as atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) when it had an excursion greater than 10 mm into the right or left atrium. PFO with and without ASA was recognized as a potential risk factor for ischemic stroke only in the past two decades. Also, patients who have suffered a cryptogenic stroke related to PFO may have a stroke recurrence,5)6) a risk that is particularly pronounced in patients with PFO and associated ASA.7)8) PFO is also associated with migraine with aura. Recent retrospective studies indicate a reduction in migraine frequency after PFO closure. Therapeutic options for PFO range from antiplatelet therapy to surgical or endovascular closure of the atrial shunt. Transcatheter closure of PFO was recently introduced in clinical practice. The goals of PFO closure are to prevent neurological events and to avoid the need for long-term anticoagulant therapy.9) This study reports the intermediate and long-term results of transcatheter closure of PFO associated with paradoxical embolism, which led to cryptogenic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), and migraine, using the Amplatzer PFO occluder at the authors' hospital. This paper also reports a case of pulmonary embolism that developed in one patient irrespective of PFO closure.

From January 2003 to June 2010, of a total of 16 patients, 15 patients with PFO (seven males, and eight females) were referred for percutaneous closure of PFO. The primary reasons for referral were stroke {12/16 (75%)}, and TIA {3/16 (18%)}. The symptoms included motor deficit in eight patients (50%), aphasia in one patient (6%), visual disturbances in four patients (25%), headache in four patients (25%), stupor in one patient (6%), and dysarthria in three patients (18%) (Table 3). The patients' conditions were initially diagnosed by neurologists. One patient who had migraine was referred for percutaneous PFO closure from pediatric outpatient department. Multiple thromboembolic events occurred in six patients prior to transcatheter device closure of PFO. The vascular risk factors were infrequent (Table 1). Cryptogenic stroke/TIA was present in eight patients (53%). ASA was present in seven patients (43%). The electrocardiographic findings before the procedure were all non-specific. Cryptogenic stroke was defined by the presence of a transient or permanent neurological deficit with associated magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence of an embolic lesion, in the absence of a clear cause.10) Ischemic stroke was defined as a cerebrovascular event with neurological symptoms lasting more than 24 hours without any sign of a primary cerebral hemorrhage. TIA was defined as a new neurological deficit with complete cessation of symptoms for 24 hours in the absence of lesions in the MRI.11) Migraine was defined as a severe recurring headache lasting from 4 to 24 hours, characterized by sharp pain, and is often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and visual disturbances.

TEE was performed to detect PFO. An agitated saline bubble study was conducted to evaluate the degree of the right-to-left shunt at rest and after the Valsalva maneuver. The air bubble test was performed in all the patients, and all of them showed positive results except for one patient, wherein the result was not positive because of poor cooperation.

The Amplatzer PFO occluder device was used in this study. It was constructed from the nitinol wires and consisted of two flat disks with a 3-mm long thin connecting waist. The right atrial disk was larger than the left atrial disk, which made it suitable for the occlusion of PFO. In this study, three sizes of the device were used, 18 mm, 25 mm, and 35 mm (Fig. 1).

The full procedure was performed under general anesthesia and was assisted by TEE through the femoral artery and vein. The NIH catheter (Cordis Europa N.V., Roden, The Ne-therlands) was advanced through an 8-Fr sheath, and pulmonary venous angiography was performed in LAO 45° view via the femoral vein. During TEE monitoring, the size of PFO with or without ASA was estimated using a balloon catheter (Boston Medical Corporation, Boston, MA, USA), and the size of the device was selected accordingly. The Amplatzer PFO occluder was implanted in the interatrial septum with great care under the water seal to prevent air embolism.

Before and after the procedure, all the patients received intravenous heparin to prevent thrombus formation, and the transseptal sheaths were removed after the activated coagulation time stabilized (activated clotting time <140 seconds) with manual compression for achieving hemostasis, and an antidote was not used.

TEE was performed before the patient was discharged, mostly at two days after the procedure. After the occlusion of PFO, the air bubble test was performed again and all the patients showed negative results. After the procedure, 100 mg/day of aspirin for six months was prescribed for all the patients.

All the patients returned for regular check-up visits at one, two, six and twelve months after the procedure, and yearly thereafter. Each patient underwent at least one TEE examination during the first six months after the procedure to confirm the adequacy of placement of the device and to document the absence of a residual shunt or thrombus formation on the device. Frequent clinical follow-ups at six- to 12-month intervals were performed with a questionnaire to evaluate the symptoms, and evidence of recurrent thromboembolic events. A detailed history of new neurological incidents was taken, and physical as well as neurological examinations were performed during each follow-up visit.

The clinical variables of the group that underwent PFO closure are listed in Table 1. There were seven male, and nine female patients. Their median age was 43.8 years (range, 10.2-69.8 years).

The procedure results are shown in Table 2. The device was successfully implanted in all the patients under general anesthesia. The sizes of the Amplatzer devices used were 18 mm (n=4), 25 mm (n=8), and 35 mm (n=4). The mean duration of the fluoroscopy time was 19.3 minutes (range, 10.0-35.6 minutes). In all the patients, the PFO was closed completely (Fig. 2A). TEE and chest PA, which were performed before the patients were discharged from the hospital, confirmed the correct placement of the device in the interatrial septum in all the patients. No procedural complications were observed.

All the patients were followed up for a mean period of 54 months (range: 10-88 months). There were no recurrent episodes of cerebrovascular accidents or TIA. Of all the 16 patients, the initial symptoms almost subsided in 10 patients (62.5%), due to which the anticoagulation therapy was discontinued. Three patients were in a minimally assisted gait state, and three patients were in a assisted daily life state, or had lt. hemianopsia, and dysarthria, respectively (Table 3). Three patients had taken anticoagulation therapy to prevent the recurrence of cerebrovascular events. A follow-up TEE was performed during the first six months after the procedure, and no residual shunt was observed. None of the patients documented atrial fibrillation before or after the implantation of the device. No dislocation of the device or fracture of the occluder construction was detected (Fig. 2B). The symptoms in the patient who had migraine subsided after occlusion of the PFO. However, the patient who developed pulmonary embolism was an exceptional case. A 55-year-old woman who had an acute infarction in the left middle cerebral artery was admitted to the authors' hospital due to the development of dysarthria and right-sided weakness, and recurrence of stroke was detected on an MRI scan (Fig. 3). The patient was referred to the Pediatric Department and she underwent PFO closure with an 18 mm Amplatzer PFO occluder. During a follow-up check-up at five months after the PFO closure, the patient had dyspnea and was readmitted to the hospital via the ER. The patient's oxygen saturation was found to be 94-95%, and chest X-ray showed a prominent right hilum (Fig. 4). The 2D echocardiogram revealed severe pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular dysfunction, and tricuspid regurgitation {TR G (III)/VI; TR peak pressure: 82.46 mmHg} (Fig. 5). Neither thromboembolism nor a shunt was observed in this patient treated using the PFO Amplatzer occluder (Fig. 6). However, acute pulmonary embolism was found on the chest CT angiogram (Fig. 7). Hence, 25000 UI bolus of heparin was injected, following which 12 UI/kg/hr of heparin was infused. This protocol was discontinued after the fourth day of heparin administration because the aPTT was 60-90 seconds and the international normalized ratio was 2-3. The patient's symptoms improved after two days of hospital admission. A lower extremity doppler sonography was performed to identify the cause of the pulmonary embolism, but no deep vein thrombosis was detected. No sources for embolism were found either on the abdominal pelvic CT or. Ten days after the pulmonary embolism, the previous RV dysfunction was no longer observed on the 2-D echo, and the patient had slight sequelae.

PFO has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cryptogenic stroke and TIA due to paradoxical embolism, and in the pathogenesis of migraine.12) The increased risk of stroke in patients with migraine could be explained by the patients' increased propensity to paradoxical embolism.2) Meta-analyses of observational studies have indicated that the prevalence of PFO is approximately three times higher in patients with cryptogenic stroke and migraine than in the controls. Conversely, the observational evidence indicates a two to three fold increased prevalence of migraine and cerebrovascular events in PFO carriers.12) The analysis of the 16 patients who underwent percutaneous closure of PFO with Amplatzer devices demonstrated the relative safety of percutaneous transcatheter PFO closure in patients with cryptogenic stroke or TIA. Over the course of 54 months, 16 patients were referred for PFO closure. The primary reasons for referral was the history of embolic events in 15 patients, which was determined by the clinical diagnosis of TIA or stroke, as confirmed via MRI, and migraine in one patient. All the patients had PFO, and seven patients (43%) had ASA. Two recent TEE studies confirmed the increased prevalence of PFO and ASA in young patients who had experienced stroke due to unexplained causes.13)14) In a meta-analysis of case control studies, Overell et al.15) concluded that the relative risk of stroke compared with non-stroke controls increased by a factor of 1.83 {confidence interval (CI): 1.25-2.66} if a PFO was present. In the patients with both PFO and ASA, the relative risk of stroke was 4.96 (CI: 2.36-10.39). Previous trials of transcatheter PFO closure (on a total of 538 patients) have documented a recurrence rate of 0-3.2% of stroke or embolism after a one-year follow-up, depending on the device used.16-19) Studies that involved newer devices, including the Amplatzer PFO occluder, have shown a recurrence rate of <1% of stroke and embolism and an occlusion rate of 96-100%.17-19) The authors' experience revealed a 0% recurrence of embolic events in these 16 patients who underwent PFO closure, a 100% procedural success rate, and a combined complication rate of 0%, with a mean follow-up period of 54 months (range: 10-88 months). However, embolization remains one of the possible complications. Other serious complications that occur in less than 1% of cases are infection, erosion into the pericardium or aorta at the rim of the device, a new ASD caused by the tearing of the thin septum primum by the lower rim, atrial fibrillation, and palpitations that are not common and usually subside spontaneously.20)

In this study, one patient developed pulmonary embolism without a known cause, despite an extensive evaluation. If this patient had not been treated with the transcatheter closure device; the Amplatzer PFO occluder when she had a stroke recurrence (second attack), she would have had a third attack of stroke, rather than developing only pulmonary embolism. Therefore, it can be concluded that transcatheter closure of PFO with the Amplatzer PFO occluder appears to be a promising therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with a history of cryptogenic stroke or TIA. Also, this procedure had a high success rate, a low rate of complications, and a low frequency of recurrent systemic thromboembolic events, and it avoids the need for lifelong anticoagulation therapy. It especially seemed to have more benefits in those cases in which the patient was younger than 55 years, and had no identifiable cause of his/her thromboembolic event, except for a PFO with/without ASA. In this study, the symptoms in one patient who had migraine subsided after the occlusion of PFO. Earlier studies have also indicated that migraine frequency might decrease after PFO closure.21)22) Migraine improves spontaneously with age,23) however, and any kind of intervention has a high placebo response in migraine, which can reduce the migraine frequency by upto 70%.24)25) Thus, there is a debate on performing PFO closure for the prevention of migraine.

However, this study had several limitations. It involved a small number of patients who had cryptogenic stroke (n=12) or TIA (n=3) {eight patients (53%)} and migraine (n=1), and also the follow-up period was not long enough. Hence, randomized, controlled trials are necessary to determine if the proposed approach is preferable to medical therapy for the prevention of recurrent stroke or as a primary treatment for patients with migraine headache.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Amplatzer PFO occluder (AGA Medical Corporation) is a self expandable, double disc device made from Nitinol wire mesh. The two discs are linked together by a short connecting waist allowing free motion of each disc.

Fig. 2

PFO occlusion using the Amplatzer PFO occluder. A: the selective superior vena cava angiography after the implantation of Amplatzer PFO occluder (arrow). B: the simple chest radiography, lateral view 5 months after PFO closure (arrow). PFO: patent foramen ovale.

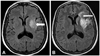

Fig. 3

Recurrence stroke was detected on an MRI scan. A: 1st acute infarction in the left middle cerebral artery-left frontotemporal lobe, insular cortex, and basal ganglia (arrow). B: 2nd acute infarction (2 months later)-left frontal lobe (arrow).

Fig. 4

Chest X-ray (sitting position) shows prominent right hilum and decreased pulmonary vascularity when the patient was admitted again via emergency room with dyspnea, five months after the patent foramen ovale closure.

Fig. 5

Patients' 2D echocardiogram revealed severe pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular dysfunction, and tricuspid regurgitation. A: the 2D echocardiogram (2 chamber view) revealed right ventricular dysfunction (right ventricle is larger than the left ventricle). B: pulmonary hypertension and tricuspid regurgitation (arrow). 2D: 2-dimensional, RV: right ventricle, LV: left ventricle.

Fig. 6

When the patient was admitted again via emergency room with dyspnea, five months after PFO closure, neither thromboembolism nor shunt was observed in this case treated using the Amplatzer PFO occluder (arrow). PFO: patent foramen ovale.

References

1. Di Tullio M, Sacco RL, Gopal A, Mohr JP, Homma S. Patent foramen ovale as a risk factor for cryptogenic stroke. Ann Intern Med. 1992. 117:461–465.

2. Diener HC, Weimar C, Katsarava Z. Patent foramen ovale: paradoxical connection to migrane and stroke. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005. 18:299–304.

3. Oh BH, Park SW, Choi YJ, et al. Prevalence of the patent foramen ovale in young patients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease: transesophageal contrast echocardiographic study. Korean Circ J. 1993. 23:217–222.

4. Meissner I, Whisnant JP, Khandheria BK, et al. Prevalence of potential risk factors for stroke assessed by transesophageal echocardiography and carotid ultrasonography: the SPARC study. Stroke Prevention: Assessment of Risk in a Community. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999. 74:862–869.

5. Homma S, Sacco RL, Di Tullio MR, Sciacca RR, Mohr JP. Effect of medical treatment in stroke patients with patent foramen ovale: patent foramen ovale in Cryptogenic Stroke Study. Circulation. 2002. 105:2625–2631.

6. Bogousslavsky J, Garazi S, Jeanrenaud X, Aebischer N, Van Melle G. Lausanne Stroke with Paradoxal Embolism Study Group. Stroke recurrence in patients with patent foramen ovale: the Lausanne Study. Neurology. 1996. 46:1301–1305.

7. Mas JL, Zuber M. French Study Group on Patent Foramen Ovale and Atrial Septal Aneurysm. Recurrent cerebrovascular events in patients with patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm, or both and cryptogenic stroke or transient ischemic attack. Am Heart J. 1995. 130:1083–1088.

8. Agmon Y, Khandheira BK, Meissner I, et al. Frequency of atrial septal aneurysms in patients with cerebral ischemic events. Circulation. 1999. 99:1942–1944.

9. Chun KJ. Patent foramen ovale and cryptogenic stroke. Korean Circ J. 2008. 38:631–637.

10. De Castro S, Cartoni D, Fiorelli M, et al. Morphological and functional characteristics of patent foramen ovale and their embolic implications. Stroke. 2000. 31:2407–2413.

11. Kerut EK, Norfleet WT, Plotnick GD, Giles TD. Patent foramen ovale: a review of associated conditions and the impact of physiological size. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001. 38:613–623.

12. Gaspardone A, Iani C, Papa M. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale: awise approach. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2008. 9:593–602.

13. Mattioli A, Bonetti L, Aquilina M, Oldani A, Longhini C, Mattioli G. Association between atrial septal aneurysm and patent foramen ovale in young patients with recent stroke and normal carotid arteries. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003. 15:4–10.

14. Lamy C, Giannesini C, Zuber M, et al. Clinical and imaging findings in cryptogenic stroke patients with and without patent foramen ovale: the PFO-ASA Study. Atrial Septal Aneurysm. Stroke. 2002. 33:706–711.

15. Overell JR, Bone I, Less KR. Interatrial septal abnormalities and stroke: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Neurology. 2000. 55:1172–1179.

16. Onorato E, Melzi G, Casilli F, et al. Patent foramen ovale with paradoxical embolism: mid-term results of transcatheter closure in 256 patients. J Interv Cardiol. 2003. 16:43–50.

17. Windecker S, Wahl A, Chatterjee T, et al. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with paradoxical embolism: long-term risk of recurrent thromboembolic events. Circulation. 2000. 101:893–898.

18. Du ZD, Cao QL, Joseph A, et al. Transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with paradoxical embolism: intermediate-term risk of recurrent neurological events. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002. 55:189–194.

19. Bruch L, Parsi A, Grad MO, et al. Transcatheter closure of interatrial communications for secondary prevention of paradoxical embolism: single center experience. Circulation. 2002. 105:2845–2848.

20. Meier B. Closure of patent foramen ovale: technique, pitfalls, complications, and follow up. Heart. 2005. 91:444–448.

21. Morandi E, Anzola GP, Angeli S, Melzi G, Onorato E. Transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale: a new migraine treatment. J Interv Cardiol. 2003. 16:39–42.

22. Wilmshurst PT, Nightingale S, Walsh KP, Morrison WL. Effect on migraine of closure of cardiac right-to-left shunts to prevent recurrence of decompression illness or stroke or for haemodynamic reasons. Lancet. 2000. 356:1648–1651.

23. Stewart WF, Shetcher A, Rasmussen BK. Migraine prevalence: a review of population-based studies. Neurology. 1994. 44:6 Suppl 4. S17–S23.

24. Migraine-Nimodipine European Study Group M. European multicenter trial of nimodipine in the prophylaxis of common migraine (migraine without aura). Headache. 1989. 29:633–638.

25. Migraine-Nimodipine European Study Group M. European multicenter trial of nimodipine in the prophylaxis of classic migraine (migraine with aura). Headache. 1989. 29:639–642.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download