Abstract

A 77-year-old man visited our hospital complaining of aggravated exertional chest pain. He was diagnosed with syndrome X 7 years ago and underwent medical treatment in a regional hospital. Coronary angiography and echocardiography did not show any significant abnormalities. On the seventh in-hospital day, cardiogenic shock developed and echocardiography showed a dilated left ventricular (LV) cavity and severe LV systolic dysfunction. We thus inserted an intra-aortic balloon pump for hemodynamic support and were forced to maintain it because of weaning failure several times. Finally, heart transplantation was the decided necessary procedure. After successful heart transplantation, the biopsy specimen revealed a wild-type transthyretin deposition indicating senile systemic amyloidosis in the intramuscular coronary vessels and interstitium. Cardiac biopsy at the 4-year follow-up showed no recurrence of amyloid deposition.

Angina pectoris with normal coronary arteries, positive treadmill exercise testing and negative coronary spasm testing can be diagnosed as cardiac syndrome X. Such cases generally have a good prognosis. Amyloid deposition in the intramuscular coronary vessels may also present as angina with normal coronary arteries. Prognosis varies according to the type of amyloid protein. Although vascular involvement is common in patients with amyloidosis, systemic amyloidosis presenting with angina is rare. Manifestations of cardiac amyloidosis may include congestive heart failure, angina, syncope and sudden cardiac death. However, in clinical settings, it is uncommonly suspected and difficult to diagnose amyloidosis in patients complaining of chest pain with a normal coronary artery (syndrome X).

We dealt with a patient with senile systemic amyloidosis (SSA) who presented with recurrent angina pectoris and then fell into dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with severe left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction, who was then successfully treated with a heart transplantation.

In May 2005, a 77-year-old man visited our emergency department (ED) complaining of chest pain. He had intermittently experienced exertional chest pain since 1996. In 1998, he visited a regional university hospital with recurrent chest pain and was diagnosed with cardiac syndrome X. His symptoms improved with medical treatment, but intermittent chest pain continued to recur.

In July 2002, he was admitted to our hospital for surgical treatment of benign prostate hypertrophy. The treadmill test was performed because of his history of angina and the result was positive. Thus, coronary angiography (CAG) and echocardiography were also performed, which showed no significant abnormalities. Medical treatment for syndrome X was continued.

In May 2005, the patient visited our ED due to chest pain that was aggravated in both intensity and duration. He did not have an acute ill-looking appearance because the angina had subsided. Physical examination did not reveal any specific abnormalities. Vital signs were stable. Complete blood cell counts, blood chemistries, electrolyte and cardiac enzymes were all within the normal range. CAG and echocardiography, which were performed with the suspicion of unstable angina, did not show any significant abnormalities. Chest computerized tomography showed no explicable findings. Thereafter, his hospital course worsened rapidly. On the seventh hospital day, he complained of dyspnea with chest pain in a resting state. Cardiogenic shock developed. Plain chest radiography showed pulmonary edema with bilateral pleural effusion. Echocardiography showed that the LV cavity in diastole was increased (59 mm) with severe global hypokinesia. LV ejection fraction was 29% by the Simpson's method, but LV wall thickness was normal. These findings were compatible with DCM except for the normal LV wall thickness (Fig. 1). Therefore, we inserted an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) for hemodynamic support. It was necessary to maintain the IABP, due to weaning failure several times. His condition was tolerable only with maximum IABP support; whenever we tried to wean the IABP, the patient could not tolerate to the weaning due to severe chest pain. In addition, urine output was decreased.

Finally, we decided to perform heart transplantation, which was successfully performed on the 84th hospital day. The outer surface of the extracted heart specimen showed some fatty tissue and fragmented coronary vessels. The right coronary artery was relatively well preserved (the cut area measuring about 1 cm), and the serial sections revealed no intraluminal stenosis. Only the distal portion of the left anterior descending artery was contained in the specimen, and the serial sections were unremarkable. Grossly, there was no mural thrombus. The right ventricle, intraventricular septum and LV were all hypertrophied (especially the right ventricle), measuring 0.9, 1.7 and 1.5 cm in thickness, respectively. The cut surface of the heart muscle showed no infarct or fibrosis (Fig. 2). The surgical specimen revealed amyloid deposition in the intramuscular coronary vessels and interstitium (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemical staining of amyloid protein was positive for transthyretin (TTR), but not for light chains. Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid analysis of the TTR exons did not identify any mutation. A final diagnosis of SSA was made. During a follow-up period of 4 years, the cardiac biopsy specimens showed neither recurrence of amyloid deposition nor rejection. The patient is currently doing well. He is symptom-free and his laboratory results show there are no abnormalities indicating other organ involvement.

Amyloidosis is a disorder caused by the deposition of fibril, composed of low molecular-weight subunits of a variety of serum proteins, in extracellular tissue. Many organs and systems, such as the heart, kidney, liver and autonomic nervous system can be involved. Systemic amyloidosis can be classified into primary (AL), secondary (AA), hemodialysis-associated, hereditary and senile systemic types. When the amyloidosis involves the heart, a variety of manifestations can be presented, namely right-sided heart failure, angina, syncope or presyncope, ischemic stroke due to intra-cardiac thrombi and LV hypertrophy with restrictive physiology. Although heart involvement in AL amyloidosis has a very poor prognosis, with an expected survival of 5 months, SSA has a relatively good prognosis.1) According to an autopsy study, SSA is a frequent finding in elderly people. Cornwell et al.2) demonstrated that approximately 50% of patients over the age of 60 years had senile cardiac amyloidosis.

There have been many case reports about symptomatic ischemic heart disease resulting from obstructive intramural coronary amyloidosis.3-11) The involved vessels are typically small and intramyocardial. On the other hand, since the epicardial coronary arteries are typically spared, CAG has normal or clinically insignificant findings.3)4)9)10) Cardiac amyloidosis is very rarely presented as DCM.5)12-14) In most cases of cardiac amyloidosis, echocardiographic features include ventricular atrial wall thickening and normal size of the ventricular-chamber, unlike hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. However, echo-cardiographic features in DCM caused by intracoronary amyloidosis are global hypokinesia of the LV with dilated LV cavity and normal LV wall thickness.15)

Our case is the first report that recurrent and progressive angina pectoris and DCM developed sequentially in SSA. The pathogenesis of DCM in cardiac amyloidosis has not yet been established. In our case, DCM developed just after the presentation of unstable angina. The surgical specimen revealed no fibrosis in the myocardium. Based on this finding it is conceivable that DCM could develop as a result of severe persistent myocardial ischemia in SSA. Considering the absence of fibrosis in our patient's myocardium, the myocardium may have been in a hibernating state at that time. Although a hibernating myocardium is a reversible state, in this case, it seemed to be irreversible due to the progression of coronary amyloidosis.

Actually, it is uncommon to suspect, and difficult to diagnose amyloidosis in patients presenting with angina before autopsy or heart biopsy is performed. Because an accurate diagnosis has a significant influence on the management and prognosis, clinicians have to consider amyloidosis as a differential diagnosis in the evaluation of angina pectoris patients with a normal coronary arteries. Endomyocardial biopsy should be considered as a diagnostic method in suspicious patients,16)17) though endomyocardial biopsy is not always required; biopsy of the skin, rectal mucosa, lung and aspirated abdominal fat are useful for its definitive diagnosis instead. As shown in our case, SSA does not recur in a transplanted heart18) while AL amyloidosis usually does progress into the transplanted heart.19)20) Therefore, heart transplantation can be an effective therapeutic option in SSA patients who do not response to intensive medical treatment.18)

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Echocardiographic findings. A: end diastolic period of previous exam (July 7, 2002). B: end systolic period of previous exam (July 7, 2002). C: end diastolic period of this exam (June 23, 2005). D: end systolic period of this exam (June 23, 2005).

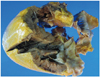

Fig. 2

Gross finding of the extracted heart specimen. There are no mural thrombi. The right ventricle, intraventricular septum and left ventricle were 0.9, 1.7 and 1.5 cm in thickness, respectively, all of which were hypertrophied. The cut surface of the heart muscles shows no infarcts or fibrosis.

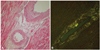

Fig. 3

Light microscopic findings of vascular amyloid deposition. A: hematoxylin-eosin staining shows deposition of pale-staining amorphous material in both blood vessel and interstitium (original magnification ×100). B: congo red staining with cross-polarized microscopy shows that a green birefringence characteristic of amyloid is apparent (original magnification ×100).

References

1. McCarthy RE 3rd, Kasper EK. A review of the amyloidoses that infiltrate the heart. Clin Cardiol. 1998. 21:547–552.

2. Cornwell GG 3rd, Westermark P. Senile amyloidosis: a protean manifestation of the aging process. J Clin Pathol. 1980. 33:1146–1152.

3. Al Suwaidi J, Velianou JL, Gertz MA, et al. Systemic amyloidosis presenting with angina pectoris. Ann Intern Med. 1999. 131:838–841.

4. Whitaker DC, Tungekar MF, Dussek JE. Angina with a normal coronary angiogram caused by amyloidosis. Heart. 2004. 90:e54.

5. Mueller PS, Edwards WD, Gertz MA. Symptomatic ischemic heart disease resulting from obstructive intramural coronary amyloidosis. Am J Med. 2000. 109:181–188.

6. Yamano S, Motomiya K, Akai Y, et al. Primary systemic amyloidosis presenting as angina pectoris due to intramyocardial coronary artery involvement: a case report. Heart Vessels. 2002. 16:157–160.

7. Zabernigg A, Schranzhofer R, Kreczy A, Gattringer K. Continuously elevated cardiac troponin I in two patients with multiple myeloma and fatal cardiac amyloidosis. Ann Oncol. 2003. 14:1791.

8. Cantwell RV, Aviles RJ, Bjornsson J, et al. Cardiac amyloidosis presenting with elevations of cardiac troponin I and angina pectoris. Clin Cardiol. 2002. 25:33–37.

9. Kaski JC, Elliott PM. Angina pectoris and normal coronary arteriograms: clinical presentation and hemodynamic characteristics. Am J Cardiol. 1995. 76:35D–42D.

10. Ogawa H, Mizuno Y, Ohkawara S, et al. Cardiac amyloidosis presenting as microvascular angina: a case report. Angiology. 2001. 52:273–278.

11. Mesquita T, Chorao M, Soares I, Mello e Silva A, Abecasis P. Primary amyloidosis as a cause of microvascular angina and intermittent claudication. Rev Port Cardiol. 2005. 24:1521–1531.

12. Ikeda S. Unusual clinical manifestations of primary systemic AL amyloidosis: are myasthenic symptoms and dilated cardiomyopathy caused by muscular or myocardial amyloid angiopathy? Intern Med. 2006. 45:123–124.

13. Yoshita M, Ishida C, Yanase D, Yamada M. Immunoglobulin light-chain (AL) amyloidosis with myasthenic symptoms and echocardiographic features of dilated cardiomyopathy. Intern Med. 2006. 45:159–162.

14. Tsuda T, Izumi T, Shibata A. Clinical assessment of serum myosin light chain I in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Kaku Igaku. 1992. 29:1035–1039.

15. Siqueira-Filho AG, Cunha CL, Tajik AJ, Seward JB, Schattenberg TT, Giuliani ER. M-mode and two-dimensional echocardiographic features in cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 1981. 63:188–196.

16. Chae JK. A case of secondary amyloidosis involving heart. Korean Circ J. 2000. 30:1179–1183.

17. Oh SS, Youn HJ, Park JH, et al. Endomyocardial biopsy: one center's report about its role. Korean Circ J. 2008. 38:374–378.

18. Fuchs U, Zittermann A, Suhr O, et al. Heart transplantation in a 68-year-old patient with senile systemic amyloidosis. Am J Transplant. 2005. 5:1159–1162.

19. Dubrey SW, Burke MM, Hawkins PN, Banner NR. Cardiac transplantation for amyloid heart disease: the United Kingdom experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004. 23:1142–1153.

20. Falk RH. Diagnosis and management of the cardiac amyloidoses. Circulation. 2005. 112:2047–2060.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download