Abstract

Cogan's syndrome is a rare systemic inflammatory disease and can be diagnosed on the basis of typical inner ear and ocular involvement with the presence of large vessel vasculitis. We report a case of Cogan's syndrome with stable angina resulting from coronary ostial stenosis caused by aortitis.

Cogan's syndrome is a rare systemic disease that is characterized by progressive inflammation in the ocular and audiovestibular organs.1) It can be associated with other systemic inflammatory manifestations such as fever, arthralgia, anemia, skin rash, neurological disease, gastrointestinal tract disease, vasculitis, and aortitis.2)3)

We report a 42-year-old woman with Cogan's syndrome who presented with angina.

A 42-year-old female was admitted with effort angina for 2 months. She had no major risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, and family history of cardiovascular disease. Five years previously she had suffered tinnitus, vertigo, and hearing disturbance that progressed to sensorineural hearing loss despite medical therapy. Four years previously she had been treated for recurrent ocular problems such as red eyes, photophobia, ocular pain, and increased tearing for 2 years.

At the time of admission, brachial blood pressures were 90/50 mmHg in the left arm and 96/57 mmHg in the right arm. The pulse rate was 64 beats per minute and respiration rate was 16 breaths per minute. Her body temperature was 36.5℃. A diastolic murmur at the cardiac base and systolic bruits over bilateral subclavicular area were heard. No abnormal physical findings were observed in the abdomen, joints, and skin. The neurological examination was entirely normal, except for neurosensory deafness. Ophthalmologic examination showed that her visual acuity, corneas, anterior chambers, pupils and iris were normal at that time.

The laboratory test results were as follows: white blood cell count 8,100/mm3, hemoglobin 10.7 g/dL, platelet count 439,000/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 73 mm/hr, C-reactive protein 2.6 mg/dL. She tested negative for autoimmune tests (antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, rheumatoid factors, antiphospholipid antibodies, complements) and negative for syphilis serology tests (VDRL, FTA-Abs).

The resting electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with non-specific ST-T changes (Fig. 1A). However, during the treadmill test ischemic ST segment depression appeared at stage 2 of the Bruce protocol (Fig. 1B). Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed normal ejection fraction (68%), normal aortic root size (2.8 cm) and normal chamber size (diastolic left ventricular dimension: 5.5 cm, systolic left ventricular dimension: 3.4 cm). The transesophageal echocardiogram revealed retracted tips of aortic cusps (Fig. 2A), moderate aortic regurgitation (Fig. 2B), and thickened wall of the descending thoracic aorta (Fig. 2C).

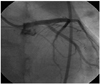

The coronary angiography showed stenoses at both the left (Fig. 3A) and right coronary ostia (Fig. 3B). The aortography demonstrated stenosis at both subclavian arteries (Fig. 3C), but the renal arteries were intact. Intravascular ultrasound (iLab 40 MHz; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) showed negative remodeling and stenoses with tissue proliferation at both coronary artery ostia (Fig. 4). The patient underwent percutaneous coronary intervention at the left main ostium with a drug eluting stent (Endeavor Resolute, Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) (4.0×15 mm) (Fig. 5). Her effort angina subsided. To control the active stage of the vasculitis, prednisolone 50 mg per day was given. After 4 weeks, her erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein normalized. However, permanent hearing loss persisted.

Cogan's syndrome is an uncommon systemic inflammatory disease characterized by involvement of the eyes and the inner ear.2) It was defined by David Cogan, an ophthalmologist, in 1945 as a nonsyphilitic keratitis and an audiovestibular function disorder resembling Meniere's disease occurring within 2 years of each other.1) It is classified into two types, typical and atypical, according to the type of ocular manifestations. In the presence of interstitial keratitis, it is classified as typical type. Other ocular problems such as conjunctivitis, uveitis, scleritis, and choroiditis lead to classification as atypical type.3)

The peak incidence occurs in the third decade of life. There are no gender or racial differences in disease prevalence and its precise etiology is unknown. However, an immunologic role has been suggested by some authors because immunosuppressive agents are effective.4)5)

In addition to the ocular and audiovestibular disorders, various systemic manifestations including fever, weight loss, arthritis, arthralgia, lymphadenopathy, skin rash, neurological disorder, gastrointestinal disease, vasculitis, and aortic insufficiency are reported. The most characteristic cardiovascular manifestation of Cogan's syndrome is aortitis. Aortitis has been described in approximately 10 percent of patients and can lead to proximal aorta dilation, aortic valvular regurgitation, coronary ostial stenosis, and thoracoabdominal aneurysms.6) Our case had manifestations compatible with vasculitis or aortitis such as bilateral subclavian artery stenosis, bilateral coronary ostial stenosis, arotic valve regurgitation and thickened thoracic aortic wall. There is no difference in incidence of aortitis between typical and atypical Cogan's syndrome.3) In addition to aortitis, she had aortic regurgitation due to retracted cusps of aortic valve probably caused by valvulitis.

Differential diagnoses to consider are Takayasu's arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener's granulomatosis, Giant cell arteritis, and rheumatic arthritis.5) It is particularly difficult to distinguish between Takayasu's arteritis and the vasculitis of Cogan's syndrome in the sense that they both involve large vessel vasculitis. However, unlike Cogan's syndrome, Takayasu's arteritis does not routinely involve the eyes and ears.7-9)

The treatment of Cogan's syndrome depends on the extension of the disease. If a mild eye involvement is the only manifestation, topical glucocorticoid is the treatment of choice. But in cases of systemic vasculitis, hearing loss, or severe infection of an eye, systemic immunosuppressive therapy is required. Glucocorticoid (prednisolone 1 mg/kg) is the first choice agent.5) If the response is incomplete, the addition of another immunosuppressive agent should be considered. Methotrexate or cyclophosphamide have been found to be effective in some reports.10)11) In patients with severe ischemic symptoms or heart failure, surgical bypass grafting or aortic valve replacement should be considered.12) Our case underwent percutaneous coronary intervention with a stent to resolve angina caused by stenosis of the left main ostium.

The prognosis for maintenance of vision and resolution of inflammatory eye lesions is generally good. However, deafness generally remains permanent, even after administration of corticosteroid and immunosuppressive agents.6) Our case received glucocorticoid therapy because she had increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. After 1 month of therapy, the inflammatory indices had normalized but the deafness had not improved. Cochlear implants are effective in patients with deafness.6) She is therefore planning to undergo such a procedure. Patients without systemic disease generally have a good prognosis and an average life expectancy.1) However, other patients may require prolonged treatment because of recurrent hearing loss or other morbidities. Patients who develop serious vasculitis, such as aortitis, have an increased risk of death due to complications.1) Therefore, early assessment and treatment for systemic inflammation are needed to prevent life threatening complications.2)

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Exercise electrocardiogram. A: baseline electrocardiogram shows normal sinus rhythm with nonspecific ST-T changes. B: electrocardiogram during exercise at Bruce protocol stage 2 reveals significant ST segment depressions at lead II, III, aVF, V4, V5, V6. |

| Fig. 2Transesophageal echocardiogram shows retracted tips of aortic cusps in systolic phase (A), moderate aortic regurgitation in diastolic phase (B), and increased wall thickening at the descending thoracic aorta (C). Arrow indicates thickened intima. |

| Fig. 3Angiography shows ostial left main stenosis (A), ostial right coronary stenosis (B), and bilateral subclavian stenosis (C). A: right anterior oblique view. B: left anterior oblique view. C: anteroposterior view. |

References

1. Mazlumzadeh M, Matteson EL. Cogan's syndrome: an audiovestibular, ocular, and systemic autoimmune disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007. 33:855–874.

2. Chynn EW, Jakobiec FA. Cogan's syndrome: ophthalmic, audiovestibular, and systemic manifestations and therapy. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1996. 36:61–72.

3. Grasland A, Pouchot J, Hachulla E, Bletry O, Papo T, Vinceneux P. Typical and atypical Cogan's syndrome: 32 cases and review of the literature. Rheumatology. 2004. 43:1007–1015.

4. Haynes BF, Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Mason P, Fauci AS. Cogan syndrome: studies in thirteen patients, long-term follow-up, and a review of the literature. Medicine. 1980. 59:426–441.

5. Vollertsen RS, McDonald TJ, Younge BR, Banks PM, Stanson AW, Illstup DM. Cogan's syndrome: 18 cases and a review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc. 1986. 61:344–361.

6. Gluth MB, Baratz KH, Matteson EL, Driscoll CL. Cogan syndrome: a retrospective review of 60 patients throughout a half century. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006. 81:483–488.

7. Raza K, Karokis D, Kitas GD. Cogan's syndrome with Takayasu's arteritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998. 37:369–372.

8. Chun KJ, Kim SI, Na MA, Choi JH. Bilateral ostial coronary artery lesions in a patient with Takayasu's arteritis. Korean Circ J. 2004. 34:118–119.

9. Park JS, Lee HC, Lee SK, et al. Takayasu's arteritis involving the ostia of three large coronary arteries. Korean Circ J. 2009. 39:551–555.

10. Riente L, Taglione E, Berrettini S. Efficacy of methotrexate in Cogan's syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1996. 23:1830–1831.

11. Orsoni JG, Zavota L, Vincenti V, Pellistri I, Rama P. Cogan syndrome in children: early diagnosis and treatment is critical to prognosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004. 137:757–758.

12. McCallum RM. Cogan's syndrome. Current Ocular Therapy. 1993. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company;410.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download