Abstract

Takayasu's arteritis (TA) is a nonspecific, chronic and stenotic panarteritis which usually involves the aorta and its major branches. Corticosteroid and immunosuppressants are recommended to manage the acute inflammatory phase, but their long term benefits are uncertain. Blood pressure (BP) control during the chronic phase of TA is essential to preserve renal function, which is associated with the patient's long-term prognosis and survival. Revascularization in organ damaging arterial stenosis with percutaneous angioplasty (PTA)/stenting or bypass surgery have been accepted as established treatment options in chronic complicated phase of TA. We present a case of a 31-year-old female patient with a two-day history of sudden onset oliguria and generalized edema whose acute oliguric renal failure was successfully reversed following PTA and stenting in a solitary functioning kidney with critical renal artery stenosis (RAS) caused by TA.

Takayasu's arteritis (TA) frequently affects the ascending aorta and aortic arch, causing obstruction of the aorta and its major arteries. The pathology is a panarteritis, characterized by mononuclear cells and occasionally giant cells infiltration, with marked intimal hyperplasia, medial and adventitial thickening, and, in the chronic form, fibrotic occlusion.1) Medical therapy with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants is generally recommended in active inflammatory phase of TA.1) Renal artery stenosis (RAS) is observed in the 38-40% of angiographically confirmed TA patients.2)3) The disease progress of RAS is directly associated with the aggravation of hypertension and renal function deterioration, therefore RAS constitutes a main prognostic factor of TA.4) Percutaneous angioplasty (PTA) and stenting in the context of acute oliguric renal failure due to severe RAS in a solitary functioning kidney when the function of the contralateral kidney had been completely lost due to renal artery (RA) occlusion in TA is rarely reported in the literature.5) We present a patient who developed acute oliguric renal failure due to severe RAS in a solitary functioning kidney successfully treated with PTA and stenting.

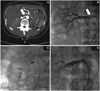

A 31-year-old female was referred to our institution with a two-day history of acute onset generalized edema and oliguria. Her vital signs were as follows: blood pressure (BP): 170/110 mmHg, pulse rate: 76/minute, respiratory rate: 23/minute, body temperature: 36.7 ℃. On examination, she appeared swollen and pre-tibial pitting edema was evident. Mild crackles were appreciated in the lower lung fields. The patient had been admitted to our institution 9 years ago for investigation of BP inequality (240/160 mmHg in left arm, 140/70 mmHg in right arm). At that time, an abdominal aortic bruit was audible and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated up to 76 mm/h with blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr) within the normal range. Given the high suspicion for RAS, we performed a Technetium99m-Diethylene Triamine Pentaacetic Acid (Tc99m-DTPA) renal scan, which demonstrated severely reduced left kidney function. RAS was confirmed with additional captopril renal scan and captopril challenge test. The patient's left RA was almost completely occluded and the right RA was normal on angiography. The patient was recommended to undergo left RA bypass surgery and corticosteroid therapy, but she declined surgery and was discharged with oral corticosteroids and antihypertensives. The patient was investigated again four years ago with a three-day history of generalized edema and reduced urine output, followed by vomiting and diarrhea secondary to gastroenteritis for one week. Her Cr at that time was elevated up to 14.7 mg/dL but subsequently returned to 1.8 mg/dL following hemodialysis. She continued to refuse bypass surgery. Despite these two episodes, she remained well on medical therapy at a local clinic, and her Cr recorded at a local laboratory was 1.9 mg/dL two weeks prior to the latest admission. Her blood chemistry when she presented to emergency triage in this time were as follows: sodium 128 meq/L, potassium 5.3 meq/L, BUN 84 mg/dL, Cr 11.8 mg/dL, C-reactive protein 0.7 mg/dL, and ESR 72 mm/h. She subsequently underwent emergent hemodialysis twice, and her Cr returned to 1.9 mg/dL with recovered urine output. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed severely contracted and non-functioning left kidney due to chronic complete occlusion of the left RA while a new, severe, right RAS was noted (Fig. 1A). Angiogram confirmed complete left RA occlusion and demonstrated 95% stenosis in the proximal portion of the right RA (Fig. 1B). By this stage, this patient's stenotic left RA and normal right RA demonstrated 9 years ago had markedly progressed to complete left RA occlusion and severe right RAS, resulting in acute oliguric renal failure. Decision was made to perform PTA and stenting for the newly diagnosed right RAS, which perfused her solitary functioning kidney. She was managed with aspirin and clopidogrel for three days prior to the procedure. Overnight intraveous saline hydration (1.5 cc/kg/h for 12 hours) and preprocedural intravenous acetlycysteine was prescribed.6) Her Cr was 2.1 mg/dL on the day of procedure.

The right common femoral artery was punctured and a 7 Fr. arterial sheath (Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA) was introduced. The 7 Fr. Vista Brite RDC guiding catheter (Cordis, Warren, NJ, USA) was adjusted to around the right RA ostium to prevent the catheter tip induced renal ostial or aortic wall damage. The "no-touch technique" was applied during the procedure using a 0.035-inch J curved-Terumo wire (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) which separated the guiding catheter tip from RA ostium and a 0.014-inch Runthrough wire (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was used to drive interventional devices (Fig. 1C).7) The lesion was pre-dilated with a Savvy 3.5×20 mm balloon (Cordis, Warren, NJ, USA) at 12 atm (3.81 mm). A 85% residual stenosis was observed after the pre-dilation. A Genesis 7×24 mm balloon expandable stent (Cordis, Warren, NJ, USA) was implanted with nominal pressure and ostial stent flaring was performed at 16 atm (7.30 mm) for 15 seconds. A residual stenosis of 50% was noticed in the main stenotic area. The procedure was completed after Amiia 6.0×20 mm balloon (Cordis, Warren, NJ, USA) inflation at 12 atm (5.12 mm). The final angiogram showed acceptable lesion dilation without complication. (Fig. 1D) A total of 120 cc of Visipaque (GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ, USA) was used. Postprocedural hemodialysis was performed for 2 hours.8) Patient was discharged after 2 days with dose-reduced antihypertensives and prednisolone. Her pre-discharge Cr was 1.7 mg/dL. The patient currently remains well with a Cr in the normal range 11 months following hospitalization.

RAS related renal failure and poorly controlled hypertension should be treated by revascularization. PTA is generally accepted as a less invasive, efficacious and safe treatment modality compared to surgical bypass, which is associated with higher morbidity.9) There are some published data demonstrating satisfactory results with PTA in treatment of TA induced RAS. Sharma et al.10) reported that PTA with or without stenting is a safe and efficacious modality to relief stenotic lesion in 20 patients with TA in a study with at least 6 months' follow-up. Tanaka et al.11) examined the efficacy of conventional balloon angioplasty and cutting balloon angioplasty for the treatment of non-arteriosclerotic RAS in 20 patients. We chose PTA as a first line treatment option for several reasons in our patient. First, she adamantly refused bypass surgery. Secondly, PTA was not inferior to surgical bypass as a treatment modality to control hypertension and preserve renal function in RAS.9) To minimize contrast induced nephropathy, we administrated sufficient amounts of saline and acetylcysteine before the procedure and used the iso-osmolar contrast agents followed by hemodialysis after intervention based on previous recommendations in the medical literature.6)8)12) The usefulness of distal protection device or carbon dioxide angiography in renovascular intervention has been controversial and we chose not employ them for our patient.13)14) Long term complications of PTA/stenting include restenosis, thrombotic occlusion, stent fracture and migration. If BP elevation or renal function deterioration occurs during follow-up, arterial patency should be examined with Duplex ultrasound, magnetic resonance, CT or selective angiography. This patient had originally been managed with four types of antihypertensive medications: nifedipine 66 mg bid, atenolol 50 mg qd, losartan 50 mg qd, and furosemide 40 mg qd at the time of admission, but only nifedipine 66 mg bid was required after PTA/stenting. At her follow up 11 months post-procedure, her Cr level was maintained within the normal range. Our patient is doing well following RA PTA and stenting against the background of acute oliguric renal failure due to TA induced critical RAS in a solitary functioning kidney. However, the optimal use of RA revascularization is poorly defined and the exact indications and clinical applications of RA revascularization in RAS are evolving.15) When making clinical decisions on renal revascularization one must assess the severity and functional significance of RAS (renal ischemia), the condition of the kidneys (nephropathy) and the association between RAS and vital organ injury.15) The risks and benefits of RA PTA will be improved by careful patient selection.15) Better results will be achieved in patients with vital organ injury, renal ischemia in the absence of nephropathy. Given the limited clinical trial outcomes and observational case reports, PTA and stenting should be considered a safe and efficacious treatment modality for TA induced acute renal failure due to RAS in a solitary functioning kidney.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Left kidney was not enhanced due to chronic complete occlusion of the left RA. Severe stenosis of right RA was treated with PTA and stenting under the "no-touch technique". A: left RA was totally occluded and the kidney was not enhanced. Near complete occlusion of right RA was visualized on abdominopelvic CT. B: severe stenosis of right RA was confirmed by renal angiography. C: PTA was performed to right RA under the "no-touch" technique. D: the lesion was successfully dilated after stent implantation without complications (arrows indicate critical right RA stenosis in abdominopelvic CT and renal angiography). RA: renal artery, CT: computed tomography, PTA: percutaneous angioplasty.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a clinical research grant from Chungbuk National University Hospital in 2009.

References

1. Liang P, Hoffman GS. Advances in the medical and surgical treatment of Takayasu arteritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005. 17:16–24.

2. Ishikawa K. Diagnostic approach and proposed criteria for the clinical diagnosis of Takayasu's arteriopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998. 12:964–972.

3. Kim KC, Park JI, Lee J, et al. Clinical characteristics of Takayasu's arteritis. Korean Circ J. 2001. 31:1106–1116.

4. Kerr GS, Hallahan CW, Giordano J, et al. Takayasu's arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 1994. 120:919–929.

5. Chandy ST, John B, Kamath P, John GT. Exclusive carbon dioxide-guided renal artery stenting in a case of Takayasu's arteritis with a solitary functioning kidney. Indian Heart J. 2003. 55:272–274.

6. Kelly AM, Dwamena B, Cronin P, Bernstein SJ, Carlos RC. Meta-analysis: effectiveness of drugs for preventing contrast-induced nephropathy. Ann Intern Med. 2008. 148:284–294.

7. Feldman RL, Wargovich TJ, Bittl JA. No-touch technique for reducing aortic wall trauma during renal artery stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 1999. 46:245–248.

8. Lee PT, Chou KJ, Liu CP, et al. Renal protection for coronary angiography in advanced renal failure patients by prophylactic hemodialysis. A randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. 50:1015–1020.

9. Bali HK, Jain S, Jain A, Sharma BK. Stent supported angioplasty in Takayasu arteritis. Int J Cardiol. 1998. 6:Suppl 1. S213–S217.

10. Sharma BK, Jain S, Bali HK, Jain A, Kumari S. A follow-up study of balloon angioplasty and de-novo stenting in Takayasu arteritis. Int J Cardiol. 2000. 75:Suppl 1. S147–S152.

11. Tanaka R, Higashi M, Naito H. Angioplasty for non-arteriosclerotic renal artery stenosis: The efficacy of cutting balloon angioplasty versus conventional anigioplasty. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007. 30:601–606.

12. Reddan D, Laville M, Garovic VD. Contrast-induced nephropathy and its prevention: What do we really known from evidence-based findings? J Nephrol. 2009. 22:333–351.

13. Singer GM, Setaro JF, Curtis JP, Remetz MS. Distal embolic protection during renal artery stenting: impact on hypertensive patients with renal dysfunction. J Clin Hypertens. 2008. 10:830–836.

14. Hawkins IF, Cho KJ, Caridi JG. Carbon dioxide in angiography to reduce the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy. Radiol Clin North Am. 2009. 47:813–825.

15. Safian RD, Madder RD. Refining the approach to renal artery revascularization. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009. 2:161–174.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download