Abstract

Background and Objectives

Placement of drug-eluting stents (DES) can be complicated by stent thrombosis; prophylactic antiplatelet therapy has been used to prevent such events. We evaluated the efficacy of cilostazol with regard to stent thrombosis as adjunctive antiplatelet therapy.

Subjects and Methods

A total of 1,315 patients (846 males, 469 females) were prospectively enrolled and analyzed for the frequency of stent thrombosis. Patients with known risk factors for stent thrombosis, except diabetes and acute coronary syndrome, were excluded from the study. All patients maintained antiplatelet therapy for at least six months. To evaluate the effects of cilostazol as another option for antiplatelet therapy, triple antiplatelet therapy (aspirin+clopidogrel+cilostazol, n=502) was compared to dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin+clopidogrel, n=813). Six months after stent placement, all patients received only two antiplatelet drugs: treatment either with cilostazol+aspirin (cilostazol group) or clopidogrel+aspirin (clopidogrel group). There were 1,033 patients (396 in cilostazol group and 637 in clopidogrel group) that maintained antiplatelet therapy for at least 12 months and were included in this study. Stent thrombosis was defined and classified according to the definition reported by the Academic Research Consortium (ARC).

Results

defined and classified according to the definition reported by the Academic Research Consortium (ARC). Results: During follow-up (561.7±251.4 days), 15 patients (1.14%) developed stent thrombosis between day 1 to day 657. Stent thrombosis occurred in seven patients (1.39%) on triple antiplatelet therapy and four patients (0.49%) on dual antiplatelet therapy (p=NS) within the first six months after stenting. Six months and later, after stent implantation, one patient (0.25%) developed stent thrombosis in the cilostazol group, and three (0.47%) in the clopidogrel group (p=NS).

Conclusion

During the first six months after DES triple antiplatelet therapy may be more effective than dual antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of stent thrombosis. However, after the first six months, dual antiplatelet treatment, with aspirin and cilostazol, may have a better cost benefit ratio for the prevention of stent thrombosis.

Since Andreas Gruentzig performed the first successful balloon angioplasty in 1977, percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) have changed considerably. The implantation of drug-eluting stents (DES) was introduced in 2001 and has been a popular catheter-based method used in clinical practice worldwide. The DES has noticeably reduced the frequency of restenosis, which was one of the most difficult problems associated with bare metal stents. Large scale studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of DES for reducing the frequency of restenosis and major cardiac events.1-7) However, long term follow up studies have reported various additional problems such as stent thrombosis. Treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy has reduced the frequency of stent thrombosis in patients treated with DES.8)

The goal of this prospective randomized trial was to evaluate the efficacy of the antiplatelet agent cilostazol for the prevention of stent thrombosis in patients with DES intervention.

Patients that received coronary artery intervention using the sirolimus-eluting stent (Cypher®, Cordis Corporation, USA) and the paclitaxel-eluting stent (Taxus®, Boston Scientific Corporation, USA) were prospectively enrolled from August 2006 to February 2008 at the Catholic University of Korea, St. Mary's Hospital, St. Paul's Hospital, Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hosptial, Daejeon St. Mary's Hospital, St. Vincent's Hospital, and Incheon St. Mary's Hospital, all in Korea.

Patients with factors that increased their risk for the development of acute or subacute stent thrombosis such as patients with severe calcification on fluoroscopy, bifurcated lesions treated with the T stent technique and Y stent technique, the stent cross-over technique used for bifurcated lesions with a side branch >2.5 mm, overlapping of two stents in one vessel, >20% residual stenosis, dissection in the distal area of the stent, patients with chronic renal failure on dialysis, those with a low ejection fraction (<40%), and patients with severe protrusion of tissues or thrombus. In addition, patients on anticoagulation therapy because of atrial fibrillation and patients that had a left main coronary artery intervention were also excluded. Furthermore, patients that had to change antiplatelet medications during the trial due to complications and those that did not comply with taking their medication were also excluded. However, the interrupted use of aspirin for a procedure with the replacement by other antiplatelet agents temporarily was not an indication for exclusion. Coronary stenting was performed according to standard intervention techniques; the final balloon angiography, the method used for implantation of stents, and the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockers were based on the operator's decisions.

All patients were instructed to take 100 mg aspirin for the rest of their lives. During the initial six months after the PCI, all patients received 300 mg clopidogrel administered as a loading dose, and 75 mg was given as a maintenance dose. Cilostazol, 100 mg, was given twice a day. The patients were divided into a triple antiplatelet therapy group and a dual antiplatelet therapy group. Starting from six months after the PCI, two types of antiplatelet agents were administered until the completion of the study. The antiplatelet agent used in addition to aspirin, was clopidogrel or cilostazol, which was assigned randomly to the dual antiplatelet therapy group and the triple antiplatelet therapy group. The group that received aspirin and clopidogrel was the clopidogrel group, and the group that received aspirin and cilostazol was the cilostazol group. All patients were regularly followed and examined in the outpatient clinic.

A comparison of the dual antiplatelet therapy group with the triple antiplatelet therapy group was performed on patients taking antiplatelet agents for longer than six months after stent implantation. In addition, a comparison of the clopidogrel group and the cilostazol group was performed on the patients taking antiplatelet agents for longer than 12 months after stent implantation. To resolve the problems associated with subjective definitions of stent thrombosis, the Academic Research Consortium (ARC), in 2007, divided stent thrombosis into three types: definite, probable, and possible, and based on the ARC the time of the occurrence; that is, from the intervention to the time of the onset of clinical symptoms, early (within 1 month), late (within 1 year), and very late (after 1 year) groups were defined. We used the definition of stent thrombosis as defined by the ARC criteria.9) The study was terminated in patients that developed stent thrombosis, at the last outpatient visit, or without drug interruption for longer than four days.

All data are presented as the mean±standard error using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) statistical software (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). For the comparison of categorical data in each therapy group, the chi-square test was applied, and for comparison of continuous data, the t-test was used. Cases with a p less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

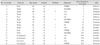

There were 1,315 patients that took antiplatelet agents according to the study protocol for longer than six months. The average follow up period was 561.7±251.4 days. The mean age of the patients was 63.4±10.8 years. There were 846 men (64.3%) and 469 women (35.7%). The patient diagnoses included: ST elevation myocardial infarction in 11.2%, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina in 58.2%, and stable angina in 30.6%. Stent thrombosis developed in 15 cases (1.14%). The onset of symptoms developed between day 1 after the intervention and day 657; eight patients developed symptoms within 30 days (0.6%). The clinical characteristics of the patients that developed stent thrombosis and the stents used are listed in Table 1 and 2.

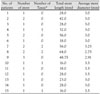

Among 1,315 patients followed for six months after stent implantation, the dual antiplatelet therapy group included 813 patients, and the triple antiplatelet therapy group 502 patients. The comparison of the two groups with regard to their age, gender, clinical diagnosis and the risk factors for coronary artery disease showed not significant differences. There were 41.6% of the patients with multivessel disease in the triple antiplatelet therapy group compared to 28.9% in the dual antiplatelet therapy group (p<0.001). Comparison of the implanted DES in the dual antiplatelet therapy group with the triple antiplatelet therapy group showed that the number of stents used (1.56±0.74, 1.70±0.94, p<0.001), the number of Taxus® stents (0.50±0.75, 0.74±0.1, p<0.001), the total length of the stents (34.08±20.08 mm, 40.16±24.03 mm, p<0.001), and the mean diameter of the stents (3.24±0.56 mm, 3.16±0.48 mm, p<0.05) in the two groups were significantly different. Stent thrombosis developed in 11 cases (0.84%), and according to the ARC definitions, in the dual antiplatelet therapy group there were three and one definite and possible cases, respectively; in the triple antiplatelet therapy group there were one, five and one definite, probable, and possible cases respectively. The comparison of the development of stent thrombosis according to treatment methods showed that the dual antiplatelet therapy group had four cases (0.49%), the triple antiplatelet therapy group had seven cases (1.39%); although the tendency was higher in the triple antiplatelet therapy group, the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (Table 3).

There were 1,033 patients that were followed for a minimum of 12 months, after the intervention. According to the method of random addition of the second antiplatelet agent to aspirin, the patients were divided into the cilostazol treatment group (n=396) and the clopidogrel treatment group (n=637), and subsequently followed for a mean of 463.9±220.4 days. Comparison of the two groups showed no significant differences with regard to their age, gender, clinical diagnosis, risk factors for coronary artery disease, and the distribution of multivessel disease. In addition, comparison of the implanted DES, the number of stents used (1.58±0.84, 1.56±0.85, p=NS), the number of Taxus® stents (0.51±0.57, 0.75±0.82, p=NS), the total length of the stent (37.03±21.07 mm, 36.53±22.00 mm, p=NS) and the average diameter of the stent (3.20±0.58 mm, 3.20±0.50 mm, p=NS), showed no significant differences between the two groups. The follow up observation period for the clopidogrel treatment group was significantly longer (436.0±207.4 days, 480.8±226.9 days, p<0.005); stent thrombosis developed in four cases (0.38%). According to the ARC definitions, two cases were probable and two cases were possible. In the cilostazol treatment group, there was 1 case (0.25%) of stent thrombosis, and in the clopidogrel treatment group, there were three cases (0.47%). No statistically significant difference between the cilostazol treatment group and the clopidogrel treatment group was not detected for stent thrombosis (Table 4).

Since DES implantation can suppress the formation of the neointima following mechanical injury, it prevents restenosis, which was a significant complication associated with bare metal stents. However, although stent thrombosis developing after DES implantation is rare,10) in the papers presented at the 2006 European Society of Cardiology, and since then, the mortality and the incidence of myocardial infarction associated with DES have been reported to be higher than with bare metal stents, and thus there is significant concern about the safety of DES.8)11-18) However, studies have demonstrated that the frequency of early stent thrombosis and late stent thrombosis in bare metal stents and DES are not significantly different.19-21) However, the risk for very late stent thrombosis with a DES has been reported to be higher than with a bare metal stent. This was the motivation for changing the treatment guidelines for the duration of clopidogrel administration. For patients with DES, at the time of its approval by the US food and drug administration for wide clinical use, the dual antiplatelet treatment of Cypher® for longer than three months and of Taxus® for longer than six months was recommended. However, the 2005 treatment guidelines of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC), recommended clopidogrel for 12 months after DES implantation, and the 2007 treatment guidelines, recommended treatment for a minimum of 12 months; in addition, the method of antiplatelet treatment has been changed.22)

The development of stent thrombosis could not be explained by one mechanism or a single causative factor. It has been shown that in addition to patient factors, numerous factors such as stent problems, problems with the stent implantation procedure, reactions to antiplatelet agents, and the characteristics of the lesion are involved in combination. Risk factors associated with stent thrombosis such as, diabetes, chronic renal failure, left ventricular dysfunction, in cases performed on bifurcated lesions or thin and long lesions, in cases where the stents were not dilated sufficiently and thus residual stenosis remained, or dissection have been previously reported. The AHA/ACC has stated that large scale studies are needed to study the risk factors associated with antiplatelet treatment and stent thrombosis to determine optimal patient management.

Cilostazol is a phosphodiesterase III blocker; it is a drug that exerts the dual effects of suppression of thrombus aggregation and proliferation of the neointima. Lee et al.23)24) reported that after bare metal stent implantation, cilostazol has suppressive effects on the development of thrombi in patients with high risk factors for developing a thrombus, such as reducing restenosis in patients with diabetes after DES implantation. Cilostazol is an antiplatelet agent widely used after stent implantation together with aspirin and clopidogrel. However, a cost benefit analysis of triple therapy, adding cilostazol to the standard dual therapy, has not been conducted. In this study, 1,315 patients were enrolled with an average follow up of 561.7±251.4 days. Based on the ARC definitions, stent thrombosis developed in 15 cases (1.14%). The frequency of stent thrombosis is different, depending on the definition of stent thrombosis used in a study. In studies reporting less than a 1% frequency of stent thrombosis, the length of the stent and the number of stents used were significantly different from this study. In a study on 260 patients comparing triple therapy and dual therapy including cilostazol, after DES implantation, stent thrombosis occurred in 0.4% in each group, with no significant difference detected.25) However, in these prior studies, the ARC definitions were not used and thus the frequency of stent thrombosis was reported to be somewhat lower then in this study. With regard to patients with diabetes, during 15 months of follow up after DES implantation, if the definitions used included: definite, probable and possible, the frequency increased to 2.4%.26) Comparing our study with such studies, showed a lower frequency of stent thrombus in this study. In addition, we did not find a significant difference in the frequency of stent thrombosis according to dual or triple antiplatelet treatment. Therefore, with regard to the cost benefit ratio dual therapy is more cost effective than triple therapy. Within the first six months from the stent implantation, the prevention of stent thrombosis with the combination of aspirin and cilostazol was comparable to the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel. Even after six months, the frequency of stent thrombosis was lower than in previous studies. The patients in our study continued to take two types of antiplatelet agents even after six months, which may have prevented stent thrombosis. Further study is needed comparing monotherapy and combination treatments. The limitations of this study include the following. Only patients with continuous intake of antiplatelet agents could be assessed in the outpatient clinics. Therefore, for patients that discontinued taking antiplatelet agents intentionally or those that could not be assessed due to transfer to another hospital the study was terminated and thus many patients were lost. In addition, this study was an open label study, and the investigators were not blind to the treatment. In regard to the use of the ARC definitions, some deaths might not have been classified inappropriately; therefore, the diagnosis of stent thrombosis might not have been completely accurate. The triple antiplatelet therapy group, had a significantly longer length of the stent and the number of stents used was greater; this suggests that there might have been some bias in assigning patients to the triple therapy treatment group.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed no significant difference between triple and dual treatment groups for the prevention of stent thrombosis after DES. Further study is need with large randomized blinded trials to determine optimal antiplatelet therapy for patient undergoing stent implantation.

Figures and Tables

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the grants of The research foundation of the internal medicine of The Catholic University of Korea.

Part of this study was presented as an abstract at the 51st Annual Scientific meeting of the Korean Society of Cardiology in 2007 and the ESC Congress in 2008.

References

1. Kim KH, Jeong MH, Hong SN, et al. The clinical effects of drug eluting stents for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis. Korean Circ J. 2005. 35:443–447.

2. Yang TH, Hong MK, Park KH, et al. Primary siroliums-eluting stent implantation for patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2005. 35:672–676.

3. Jeong YS, Cho KH, Park YW, Kim SM, Kim DI, Kim DS. Siroliumus-eluting stent for the treatment of in-stent restenosis: comparison with cutting balloon angioplasty. Korean Circ J. 2006. 36:66–71.

4. Kim DB, Seung KB, Kim BJ, et al. Utilization pattern of drug-eluting stents and prognosis of patients who underwent drug-eluting stenting compared with bare metal stenting in the real world. Korean Circ J. 2006. 36:178–183.

5. Kim BK, Oh SJ, Jeon DW, et al. Clinical outcomes following sirolimus-eluting stent implantation in patients with end-stage renal disease. Korean Circ J. 2006. 36:424–430.

6. Park JS, Kim YJ, Shin DG, et al. Clinical and angiographic outcome of sirolimus-eluting stent for the treatment of very long lesions. Korean Circ J. 2006. 36:490–494.

7. Kim W, Jeong MH, Cho JY, et al. The preventive effect on instent restenosis of overlapped drug-eluting stents for treating diffuse coronary artery disease. Korean Circ J. 2006. 36:17–23.

8. Park DW, Park SW. Stent thrombosis in the era of the drug-eluting stent. Korean Circ J. 2005. 35:791–794.

9. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case of standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007. 115:2344–2351.

10. Park SH, Hong GR, Seo HS, Tahk SJ. Stent thrombosis after successful drug-eluting stent implantation. Korean Circ J. 2005. 35:163–171.

11. Windecker S, Remondino A, Eberli FR, et al. Sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2005. 353:653–662.

12. Cutlip DE, Baim DS, Ho KK, et al. Stent thrombosis in the modern era: a pooled analysis of multicenter coronary stent clinical trials. Circulation. 2001. 103:1967–1971.

13. Mauri L, Hsieh WH, Massaro JM, Ho KK, D'Agostino R, Cutlip DE. Stent thrombosis in randomized clinical trials of drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2007. 356:1020–1029.

14. Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K, et al. Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet. 2007. 369:667–678.

15. Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2005. 293:2126–2130.

16. Lagerqvist B, James SK, Stenestrand U, Lindback J, Nilsson T, Wallentin L. Long-term outcomes with drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in Sweden. N Engl J Med. 2007. 356:1009–1019.

17. Camenzind E, Steg PG, Wijns W. Stent thrombosis late after implantation of first-generation drug-eluting stents: a cause for concern. Circulation. 2007. 115:1440–1455.

18. Kuchulakanti PK, Chu WW, Torguson R, et al. Correlates and long-term outcomes of angiographically proven stent thrombosis with sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents. Circulation. 2006. 113:1108–1113.

19. Stone GW, Moses JW, Ellis SG, et al. Safety and efficacy of sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents. N Engl J Med. 2007. 356:998–1008.

20. Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Pache J, et al. Analysis of 14 trials comparing sirolimus-eluting stents with bare-metal stents. N Engl J Med. 2007. 356:1030–1039.

21. Doyle B, Rihal CS, O'Sullivan CJ, et al. Outcomes of stent thrombosis and restenosis during extended follow-up of patients treated with bare-metal coronary stents. Circulation. 2007. 116:2391–2398.

22. King SB 3rd, Smith SC Jr, Hirshfeld JW Jr, et al. 2007 Focused update of the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task torce on practice guidelines: 2007 writing group to review new evidence and update the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention, writing on behalf of the 2005 writing committee. Circulation. 2008. 117:261–295.

23. Lee SW, Park SW, Hong MK, et al. Triple versus dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: impact on stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005. 46:1833–1837.

24. Lee SW, Park SW, Kim YH, et al. Drug-eluting stenting followed by cilostazol treatment reduces late restenosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: the DECLARE-DIABETES trial (a randomized comparison of triple antiplatelet therapy with dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation in diabetic patients). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008. 51:1181–1187.

25. Lee SW, Park SW, Kim YH, et al. Comparison of triple versus dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation (from the DECLARE-Long trial). Am J Cardiol. 2007. 100:1103–1108.

26. Maeng M, Jensen LO, Kaltoft A, et al. Comparison of stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and mortality following drug-eluting versus bare-metal stent coronary intervention in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2008. 102:165–172.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download