Abstract

A male infant aged 3 months and 1 week had persistently high fever with parotitis that was unresponsive to antibiotics. Mumps was identified by serologic study, but he was finally diagnosed by clinical features as having Kawasaki disease and echocardiographic findings on the 9th day of fever. Parotitis, which is unresponsive to antibiotics, should be considered Kawasaki disease even though typical symptoms are not present.

Kawasaki disease is generalized systemic vasculitis.1) Many head and neck symptoms and signs are manifested in Kawasaki disease such as bilateral nonexudative conjunctivitis, erythema of the lips, and oral mucosa and cervical lymphadenopathy. But parotitis is a very uncommon manifestation of Kawasaki disease, even though pathologic findings of the parotid gland were described in an autopsy case.2)

Here we report a case of Kawasaki disease that presented as parotitis in a 3-month-old infant.

A male infant aged 3 months and 1 week, was referred to us after presenting with a 3-day history of high fever and a left cheek mass.

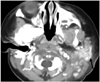

At the time of admission, body temperature was 38.7-39.7℃, heart rate was 140-150/min, respiration rate was 32-35/min. The patient looked very ill and irritable. From the posterior area of the left ear to the inferior area of the jaw, a hard mass measuring 3×4 cm was palpated, with a febrile sensation and a flare around the mass. Laboratory findings were as follows: Hemoglobin 9.7 g/dL, hematocrit 27%, leukocytes 11,820/mm3 (76.5% neutrophils, 13.4% lymphocytes, 6.4% monocytes, 0.9% eosinophils), platelets 266,000/mm3, C-reactive protein 82.7 mg/L. Amylase was 46 U/L. Other laboratory findings were negative. The patient's mumps immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) measured by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, Denka Seiken Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were negative. However, his mother's IgG and IgM were positive, and rheumatoid factor, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies were all negative. The finding of a computed tomography (CT) scan of his pharynx showed increased intensity in the left parotid gland and the adjacent lymph nodes were enlarged (Fig. 1). Therefore, pyogenic parotitis and sepsis were suspected, and antibiotics (Vancomycin, Amikacin) and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG, 1 g/day×2 days) were administered on the 1st day of admission. Afterward, the swelling in the neck area and skin flares were alleviated slightly, but the high fever persisted.

On the 5th day of admission, lip redness and fissure, conjunctival injection, and edema of the hands and feet appeared. At that time, leukocytosis and thrombocytosis were observed (leukocytes 18,220/mm3, platelets 533,000/mm3), C-reactive protein was 82.2 mg/L, and amylase was 10 U/L. Thus, Kawasaki disease was suspected and IVIG (2 g/day) and high-dose aspirin were administered. After that, the fever decreased and the overall condition of the patient improved. After 3 weeks, the patient's mumps IgG and IgM were converted to positive.

Echocardiography (on the 9th day of fever) results showed diffuse dilatation of the left main coronary artery measuring 2.8 mm (Z score >3) and saccular dilatation of the proximal left anterior descending artery measuring 4.0 mm (Z score >3) (Fig. 2). Echocardiography performed at the 1st month after disease onset showed slight regression of the coronary artery (left main coronary artery 2.8 mm, proximal left anterior descending artery 3.0 mm).

Parotitis has been reported to occur with an increased frequency in young infants born prematurely. Staphylococcus aureus has been determined to be the major pathogen cultured from these patients, and the response to antibiotics is good.3)4)

The case presented here is reported as the second case of parotitis associated with Kawasaki disease, but the first case was an adolescent.5) In this case, Kawasaki disease was not suspected because the patient was too young. Moreover, parotitis is an uncommon presentation of Kawasaki disease. The infant we treated was admitted for a mass in the posterior area of the ear with accompanying high fever and pyogenic parotitis and sepsis was suspected. Therefore antibiotics and IVIG were administered. However, on the 5th day after the administration of antibiotics (9th day of fever), conjunctival injection and lip redness appeared, and a skin rash began to appear. Subsequent administration of IVIG and high-dose aspirin reduced the clinical symptoms. Such cases of Kawasaki disease initially presenting with parotitis are very rare. So, because of unresponsiveness to antibiotics, we suspected that the parotitis was a type of autoimmune disease such as Sjögren's syndrome6) with mumps infected by maternal subclinical mumps.

The etiology of Kawasaki disease remains unknown. Although clinical and epidemiological features strongly suggest an infectious cause, efforts to identify an infectious agent in Kawasaki disease with conventional bacterial and viral cultures and serological methods have failed to do so.1) In this case, however, mumps virus was identified by serologic test and was considered as the etiology of Kawasaki disease.

Although the patient was treated with IVIG on admission day because sepsis was suspected, fever did not subside and clinical features of Kawasaki disease appeared on the 5th day of admission. Over 10% of patients with Kawasaki disease failed to respond to initial IVIG therapy as our patient shown.7) Also, there are possible different mechanisms of action of IVIG in individuals of very young age, especially below 6 months. A case of unstable angina in an adolescent previously diagnosed with Kawasaki disease at the age of 3 month was reported.8) Hence, long term follow up will be needed in this case because of treatment failure of the initial IVIG therapy and the very young age of onset.

In conclusion, infants with parotitis that is unresponsive to antibiotics and accompanied by prolonged fever, should be considered Kawasaki disease even though typical symptoms are not present.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professional from the Committee on Rheumatic fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Americal Heart Association. Pediatrics. 2004. 114:1708–1733.

2. Amano S, Hazama F, Kubagawa H, Tasaka K, Haemara H, Hamashima Y. General pathology of Kawasaki disease. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1980. 30:681–694.

3. Spiegel R, Miron D, Sakran W, Horovitz Y. Acute neonatal suppurative parotitis: case reports and review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004. 23:76–78.

4. Chiu CH, Lin TY. Clinical and microbiological analysis of six children with acute suppurative parotitis. Acta Paediatr. 1996. 85:106–108.

5. Seyedabadi KS, Howes RF, Yazdi M. Parotitis associated with Kawasaki syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987. 6:223.

6. Flaitz CM. Parotitis as the initial sign of juvenile Sjögren's syndrome. Pediatr Dent. 2001. 23:140–142.

7. Durongpisitkul K, Soongswang J, Laohaprasitiporn D, Nana A, Prachuabmoh C, Kangkagate C. Immunoglobulin failure and retreatment in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003. 24:145–148.

8. Kim BK, Lee BK, Choi DH, Shim DK. Coronary stenting in 15 year-old boy with coronary artery stenosis seconary to Kawasaki disease. Korean Circ J. 2000. 30:1300–1306.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download