Abstract

A 55-year-old male patient presented with an acute myocardial infarction. A sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) was implanted in the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD). Eight months later, there was a newly developed distal LAD lesion. An additional SES was implanted. Twenty-eight months after the index procedure of primary coronary intervention, the electrocardiogram showed ST elevation in the precordial leads and an emergency coronary angiogram showed diffuse stent thrombosis (ST) in the proximal LAD. Thirty-four months after the index procedure, coronary angiography showed a large peri-stent coronary aneurysm in the proximal LAD and focal in-stent restenosis (ISR) at the proximal edge of the distal LAD stent. On fluoroscopy, a fracture was noted in the middle part of the distal SES. A zotarolimus- eluting stent (ZES) was deployed and overlapped the restenosis and fracture sites. Forty months after the index procedure, there were no changes in the size of the aneurysm or in the other stent complications including the fracture and restenosis. At present, the patient has remained asymptomatic for eight months.

Coronary artery stents significantly reduce the risk of restenosis when compared to balloon angioplasty. Recently, drug-eluting stents (DES) have been shown to reduce neointimal hyperplasia more effectively as well as the need for repeat revascularization.1)2) However, there are a variety of stent-related complications that occur after percutaneous coronary intervention. Herein we report a case with a number of complications occurring in one patient after sirolimus-eluting stent (SES, Cypher; Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL, USA) deployment including very late stent thrombosis (VLST), stent fracture, instent restenosis (ISR), and a peri-stent aneurysm.

A 55-year-old male patient presented with a myocardial infarction associated with acute anterior ST-elevation. He had a history of diabetes and hypertension. The echocardiogram revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 36% with abnormal wall motion in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) territory before primary coronary angiography in the emergency room. Emergency coronary angiography showed total occlusion of the proximal portion of the LAD. A SES 3.5×23 mm was implanted in the proximal LAD. Eight months later, follow-up coronary angiography showed a patent LAD stent, and a newly developed distal LAD lesion. An additional SES 3.0×23 mm was implanted. Despite continuous dual antiplatelet medication with aspirin and clopidogrel, severe chest pain developed twenty-eight months after the index procedure. The electrocardiogram showed ST elevation in the precordial leads and an emergency coronary angiogram was obtained. The angiogram showed diffuse stent thrombosis (ST) in the proximal LAD (Fig. 1A). At first, the lesion was dilated with a Ryujin (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) balloon 2.5×23 mm at 10 atm (Fig. 1B). The intravascular ultrasound (IVUS, Galaxy™; Boston Scientific, Reading, PA, USA) study showed late stent malapposition (LSM) in the proximal LAD (Fig. 1C). The patient was treated with heparin and abciximab without the need for additional procedures. Repeat angiography showed that the thrombus was nearly resolved five days later (Fig. 1D). Thirtyfour months after the index procedure, a fifth follow-up coronary angiogram was obtained. The results showed a large peri-stent coronary aneurysm in the proximal LAD (Fig. 2A). The IVUS revealed positive remodeling and peri-stent aneurysm formation in the proximal LAD (Fig. 2B). There was a focal ISR at the proximal edge of the distal LAD stent (Fig. 3A). A fracture was noted in the middle part of the distal SES with fluoroscopy (Fig. 3B). A 64-slice multidetector computed tomogram (MDCT, Aquilion; Toshiba Medical Systems, Japan) demonstrated a coronary artery stent aneurysm and fracture of the stent (Fig. 4A and B). A zotarolimus-eluting stent 3.0×30 mm (ZES, Endeavor; Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) was deployed and overlapped the restenosis and fracture sites. Forty months after the index procedure, the last coronary angiogram was obtained. There were no changes in the size of the aneurysm or in the other stent complications including the fracture and restenosis. At present, triple antiplatelet therapy has been continued, and the patient has remained asymptomatic for eight months.

This case shows the development of multiple complications in a patient that had a SES implanted including VLST, stent fracture, ISR, and a peri-stent aneurysm.

ST is a rare but possibly lethal complication after implantation of a DES. VLST by definition occurs more than one year after the procedure.3) There are several mechanisms underlying the development of a ST. The most important factor is premature discontinuation of antiplatelet agents.4) Other factors include LSM, delayed endothelialization, bifurcation lesions, renal failure, diabetes, and decreased systolic heart function.4) Lately, the American Heart Association advisory board has recommended continuation of dual antiplatelet therapy for 12 months after DES placement.5) In our patient, LSM, diabetes and a low ejection fraction were thought to be possible causes of the VLST.

Stent fracture is another important potential complication after DES deployment, especially with an SES; it is a potential cause of ISR and ST elevation?6)7) Stent fracture has many possible causes, such as overexpansion of the stent struts, stent design, use of a long stent, overlapping stents, hypermobile vessels, and tortuous vessels.6)8) In this case, the exact causes of the delayed stent fracture were unknown. Two possible causes for the stent fracture are post-balloon dilatation therapy, which might have caused a strut microfracture, or a rigid and inflexible design of the SES, which occurs with a closed cell design and thick metal struts. However, post dilatation therapy is recommended to prevent stent under-expansion.

ISR is a significant problem after stent implantation. ISR usually occurs within six months after stent implantation. The mechanism responsible for restenosis is associated with neointimal formation.9) Additional risk factors for ISR include diabetes, lesion length, luminal cross-sectional area after stenting, the number and length of stents, and the plaque burden.10-14) We found in a previous study that stent fracture may be another potential risk factor for ISR.6) The patient reported here had diabetes, and stent under expansion was not observed after stent implantation. Because of the presence of focal ISR, involving the edge of the stent, as well as stent fracture, additional stent implantation was recommended. Currently, late catch-up has become a significant issue for the long-term effectiveness of DES. However, long-term angiographic studies are needed to study this issue further.

The fourth complication was peri-stent aneurysm formation. A coronary aneurysm is defined as a dilation of the coronary artery that exceeds 1.5 times the reference diameter of adjacent coronary segments that are angiographically normal.15) However, the incidence and precise mechanism of peri-stent aneurysms remain unknown. The delayed healing effects associated with LSM could have been associated with the development of an aneurysm after DES implantation. LSM is defined as a separation of one or more stent struts from the intima with no overlap with a side branch, and evidence of blood flow behind the strut. Possible explanations for an LSM include positive regional vascular remodeling, allergy to a drug, and late dissolution of a thrombus.16)17) In our case, there were several possible causes of the aneurysm. First, the most likely cause of the aneurysm formation was LSM of the stent strut. Second, the delayed healing effects associated with rapamycin and patient-specific hypersensitivity were considered responsible for formation of the aneurysm. Third, late thrombus resolution may have occurred after the second primary percutaneous coronary intervention. There are no guidelines for the ideal treatment of patients that develop a coronary stent aneurysm. Our patient had no chest symptoms and the size of the coronary aneurysm was stable. For larger aneurysms surgical excision, percutaneous coiling, or the use of a covered stent might be considered.18)19)

In conclusion, the use of a DES has been associated with a number of complications. IVUS is essential for the planning of a therapeutic strategy. Additional angiographic follow-up may be needed after stent placement. In the future, bioabsorbable polymer coated stents and more advanced stent platforms will be required to prevent these serious complications. However, guidelines are now needed for the prevention and treatment of stent induced complications.

Figures and Tables

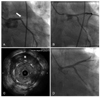

Fig. 1

Coronary angiography shows a stent thrombosis in the proximal left anterior descending artery (arrow) (A), post-balloon angioplasty (B). An intravascular ultrasound shows late stent malapposition (*) (C). Angiography after five days reveals restoration of the normal blood flow (D).

Fig. 2

Follow-up angiography reveals a large proximal left anterior descending artery aneurysm (arrow) (A) and an intravascular ultrasound shows malapposition of the stent (B).

References

1. Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, et al. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002. 346:1773–1780.

2. Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cannon L, et al. Comparison of a polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting stent with a bare metal stent in patients with complex coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005. 294:1215–1223.

3. Mauri L, Hsieh WH, Massaro JM, Ho KK, D'Agostino R, Cutlip DE. Stent thrombosis in randomized clinical trials of drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2007. 356:1020–1029.

4. Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2005. 293:2126–2130.

5. Grines CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE Jr, et al. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, American College of Surgeons, and American Dental Association, with representation from the American College of Physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. 49:734–739.

6. Yang TH, Kim DI, Park SG, et al. Clinical characteristics of stent fracture after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2009. 131:212–216.

7. Bae JH, Hyun DW, Kim KY, Yoon HJ, Nakamura S. Drug-eluting stent strut fracture as a cause of restenosis. Korean Circ J. 2005. 35:787–789.

8. Sianos G, Hofma S, Ligthart JM, et al. Stent fracture and restenosis in the drug-eluting stent era. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004. 61:111–116.

9. Hoffmann R, Mintz GS, Dussaillant GR, et al. Patterns and mechanisms of in-stent restenosis: a serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 1996. 94:1247–1254.

10. Lee CW, Park SJ. Predictive factors for restenosis after drug-eluting stent implantation. Korean Circ J. 2007. 37:97–102.

11. Kastrati A, Elezi S, Dirschinger J, Hadamitzky M, Neumann FJ, Schomig A. Influence of lesion length on restenosis after coronary stent placement. Am J Cardiol. 1999. 83:1617–1622.

12. Kastrati A, Schomig A, Elezi S, et al. Predictive factors of restenosis after coronary stent placement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997. 30:1428–1436.

13. Elezi S, Kastrati A, Neumann FJ, Hadamitzky M, Dirschinger J, Schomig A. Vessel size and long-term outcome after coronary stent placement. Circulation. 1998. 98:1875–1880.

14. Hoffmann R, Mintz GS, Mehran R, et al. Intravascular ultrasound predictors of angiographic restenosis in lesions treated with Palmaz-Schatz stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998. 31:43–49.

15. Slota PA, Fischman DL, Savage MP, Rake R, Goldberg S. Frequency and outcome of development of coronary artery aneurysm after intracoronary stent placement and angioplasty. STRESS Trial Investigators. Am J Cardiol. 1997. 79:1104–1106.

16. Mintz GS, Shah VM, Weissman NJ. Regional remodeling as the cause of late stent malapposition. Circulation. 2003. 107:2660–2663.

17. Virmani R, Guagliumi G, Farb A, et al. Localized hypersensitivity and late coronary thrombosis secondary to a sirolimus-eluting stent: should we be cautious? Circulation. 2004. 109:701–705.

18. Bavry AA, Chiu JH, Jefferson BK, et al. Development of coronary aneurysm after drug-eluting stent implantation. Ann Intern Med. 2007. 146:230–232.

19. Gurvitch R, Yan BP, Warren R, Marasco S, Black AJ, Ajani AE. Spontaneous resolution of multiple coronary aneurysms complicating drug eluting stent implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2008. 130:e7–e10.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download