Introduction

Myotonic dystrophy (MD) is an inherited disorder transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion.1) In MD, cardiac complications are the second most common cause of death in up to 30% of patients.2) The cardiac involvement in patients with MD is usually characterized by arrhythmias, mainly due to conduction system abnormalities and an increased risk of sudden death. However, the occurrence of clinical myocardial disease appears to be rare, with only occasional reports of cardiomyopathy, and little is known about the clinical course as it relates to involvement of the myocardium.3)

Case

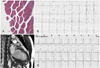

A 48-year-old male patient with a 10-year history of MD was referred for evaluation of an abnormal electrocardiogram (EKG). He had no subjective symptoms. MD was confirmed by rectus femoralis muscle biopsy that showed atrophy and degenerated fibers with internal nuclei, consistent with a myotonic myopathy (Fig. 1A). Electromyography showed myotonic discharges in several muscles. The patient had four uncles who all died because of myopathic disease before 50 years of age. The patient had a 5-year-old niece with MD and cardiac involvement. The patient's daughter had a sudden death at 18 years of age.

The clinical examination revealed signs of classic MD. He had premature balding and had a characteristically thin face, hand myotonia, and bilateral weakness of the lower extremities. His blood pressure and heart rate were 110/80 mmHg and 57/min, respectively. An initial 12-lead EKG showed first-degree atrioventricular block (PR interval, 220 msec) and intraventricular conduction delay (QRS duration, 142 msec) (Fig. 1B). The serum creatine kinase was mildly elevated, but the creatine kinase-MB isoenzyme and troponin T levels were normal. No significant arrhythmias were observed on the initial 24-hour Holter monitoring. However, an inappropriate heart rate (83/min) response with suspicious atrioventricular block at stage 4 was observed on the exercise treadmill test. Initial transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) demonstrated hypokinesia of the inferior wall with mild left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction, 45%). There were no signs of ischemic disease by coronary angiography; there was no fat infiltration or fibrosis demonstrated on cardiac MRI (Fig. 1C).

On the 1-year follow-up evaluation, intermittent left bundle branch block was observed on 24-hour Holter monitoring (Fig. 1D), and more aggravated regional wall motion abnormalities (hypokinesia of the anterolateral and inferior walls) were shown on TTE (ejection fraction, 40%) with dyspnea on exertion New York Heart Association. A permanent pacemaker insertion was considered to prevent sudden death based on American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines.

Discussion

While cardiac involvement (CI) in MD is usually characterized by arrhythmias (conduction abnormalities and tachyarrhythmias), myocardial damage with symptoms of heart failure is rare because CI is mainly due to selective degeneration of the infra-nodal conduction system.3-5) On histologic evaluation, CI in MD involves interstitial myocardial fibrosis and fatty infiltration.6) Interestingly, in the case described herein, there were no significant arrhythmias on EKG, no fibro-lipomatous changes, and no evidence of myocardial ischemia on cardiac MRI. However, the initial and follow-up EKGs showed decreased left ventricular systolic function and extended regional wall motion abnormalities. Therefore, serial EKGs may be a more useful imaging tool than CT or MRI for earlier detection of myocardial involvement in asymptomatic patients with MD.

In primary MD patients, cardiac involvement is the second most common cause of death.2) Atrioventricular block and ventricular tachyarrhythmia are considered to be the main cause of sudden death in patients with MD.7) Several studies have recommended that Holter monitoring should be performed on a regular basis.8)9) Recent pacing guidelines have recognized that asymptomatic conduction abnormalities in MD may warrant special consideration for pacing.10) In the present case, the patient showed non-specific findings on initial Holter monitoring, but treadmill testing showed a significant arrhythmia and an inappropriate heart rate. Progressive conduction abnormalities with aggravated cardiomyopathy were observed on subsequent follow-up examinations.

We therefore suggest that comprehensive evaluation with treadmill testing and an EKG may be beneficial for patients with primary MD, even when asymptomatic, to identify non-ischemic cardiomyopathy in an effort to determine the appropriate time for pacemaker insertion and prevention of life-threatening complications.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download