Abstract

We describe a 54-year-old woman with isolated pulmonary arterial hypertension accompanied by hyperthyroidism due to Graves' disease. Her pulmonary artery hypertension resolved spontaneously after restoration of euthyroidism. This case suggests that hyperthyroidism should be considered a reversible cause of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Hyperthyroidism affects the cardiovascular system in many ways. It increases heart rate and cardiac mass, promotes cardiac arrhythmias, and elevates systolic blood pressure. It also shortens the ejection period and impairs diastolic function.1)2) Rarely, pulmonary hypertension has been reported in association with hyperthyroidism.3)4) We report a patient with isolated pulmonary arterial hypertension accompanied by hyperthyroidism due to Graves' disease. The pulmonary hypertension resolved spontaneously with restoration of euthyroidism.

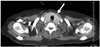

A 54-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency room with dyspnea and generalized edema. Physical examination revealed diaphoresis, jaundice, distended jugular veins, hepatomegaly, ascites, ankle edema, and decreased breath sounds in both lower lung fields. A chest roentgenogram showed marked cardiomegaly and bilateral pleural effusions. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis without neutrophilia, normal cellular liver enzymes {aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 16/12 IU/L}, mild bilirubinaemia (total bilirubin of 3.4 mg/dL), a prolonged prothrombin time of 17.7 seconds {international normalized ratio (INR) 1.7}, and a normal partial prothrombin time of 28 seconds. The patient was given oxygen through nasal cannula and was administered intravenous furosemide for pulmonary congestion. She underwent a transthoracic echocardiogram, which revealed a dilated right ventricle, reduced right ventricular systolic function, a severely elevated systolic pulmonary arterial pressure of 80 mmHg, and moderate tricuspid valvular regurgitation. The left ventricular chamber was normal sized, with a reasonable ejection fraction of 0.75 (Fig. 1A). Serum D-dimer was elevated at 2,460 ng/mL (normal, 0-500 ng/mL). A chest computed tomogram obtained to rule out pulmonary embolism revealed no evidence of pulmonary embolism. A ventilation-perfusion pulmonary scan suggested a low probability of pulmonary embolism, as well. At this point, chest CT suggested the possibility of thyroid goiter (Fig. 2). Further laboratory tests revealed a decreased serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level (less than 0.08 uIU/mL), an increased serum free thyroxine (FT4) level (4.45 ng/dL; normal, 0.89-1.76 ng/dL), and an increased serum total triiodothyronine (TT3) level (3.03 ng/mL; normal, 0.60-1.81 ng/mL). A right heart catheterization performed the following day demonstrated severely elevated systolic/mean pulmonary artery hypertension of 80/60 mmHg. The pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was normal at 10 mmHg, without evidence of intracardiac shunt. Anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies were positive at 54.7 U/mL. The patient was confirmed to have idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension and hyperthyroidism due to Grave's disease and was started on bosentan, amlodipine, and methimazole. During the following days, the patient's clinical condition gradually improved, and her body weight returned to baseline. The patient was discharged in good clinical condition without signs or symptoms of heart failure. TSH was still low (<0.08 uIU/mL), and TT3 was slightly elevated (2.53 ng/mL), but FT4 was within the normal laboratory range (1.63 ng/dL).

Approximately four weeks later, a transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a normal sized right ventricle with good systolic function, improved systolic pulmonary artery pressure of 35 mmHg, and trivial tricuspid valvular regurgitation (Fig. 1B).

TT3 improved (2.28 ng/mL), and FT4 remained in the normal range (1.34 ng/dL). We decided to discontinue bosentan, which is capable of masking the effect of the euthyroid state. After discontinuation of bosentan, the patient remained in good condition, without symptoms or signs of right-sided heart failure. Six months later, the patient had normal pulmonary artery pressure. She remained euthyroid on methimazole (Table 1).

Many of the clinical manifestations of hyperthyroidism are attributable to the ability of thyroid hormones to alter cardiovascular hemodynamics. The usual manifestations occur secondary to high cardiac output causing left-sided heart failure. However, there is an increasing body of evidence suggesting that hyperthyroidism might cause reversible pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), resulting in right-sided heart failure. This phenomenon might be underdiagnosed, because pulmonary artery pressure usually returns to the normal range after a euthyroid state is achieved.5) The potential pathogenic mechanisms of hyperthyroidism-related PAH remain unclear. It has been postulated that the pathogenesis of PAH in hyperthyroid patients is similar to that of other autoimmune diseases related to PAH.6) However, Siu et al.7) reported that there was no significant difference in the prevalence of positive autoimmune antibodies between patients with PAH and those without PAH, or in the resolution of PAH after successful antithyroid treatment regardless of the underlying etiology of hyperthyroidism. It is uncertain which sub-group of patients is inclined to develop PAH. However, PAH obviously develops in some patients. Therefore, it is crucial to recognize hyperthyroidism as a reversible cause of PAH.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Echocardiography in a patient with isolated pulmonary arterial hypertension accompanied by hyperthyroidism. A: echocardiography on admission. The right atrium is markedly enlarged, and the right ventricle is compressing the left ventricle into a D-shape. The left ventricle is normal-sized. B: echocardiography after restoration of euthyroid state. The right atrial and ventricular sizes have normalized after resolution of hyperthyroidism. RV: right ventricle, LV: left ventricle, RA: right atrium, LA: left atrium.

References

1. Kahaly GJ, Dillman WH. Thyroid hormone action in the heart. Endocr Rev. 2005. 26:704–728.

2. Klein LI, Danzi S. Braverman LE, Utiger RD, editors. The cardiovascular system in thyrotoxicosis. Werner & Ingbar's The Thyroid: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 2005. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;559–568.

3. Soroush-Yari A, Burstein S, Hoo GW, Santiago SM. Pulmonary hypertension in men with thyrotoxicosis. Respiration. 2005. 72:90–94.

4. Lozano HF, Sharma CN. Reversible pulmonary hypertension, tricuspid regurgitation and right-sided heart failure associated with hyperthyroidism: case report and review of the literature. Cardiol Rev. 2004. 12:299–305.

5. Ismail HM. Reversible pulmonary hypertension and isolated right-sided heart failure associated with hyperthyroidism. J Gen Intern Med. 2007. 22:148–150.

6. Ojamaa K, Balkman C, Klein IL. Acute effects of triiodothyronine on arterial smooth muscle cells. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993. 56(1):Suppl. S61–S66.

7. Siu CW, Zhang XH, Yung C, Kung AW, Lau CP, Tse HF. Hemodynamic changes in hyperthyroidism-related pulmonary hypertension: a prospective echocardiographic study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007. 92:1736–1742.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download