Introduction

It is rare for an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) to occur without angiographic evidence of atherosclerosis. Possible mechanisms for such an event include coronary artery spasm, coronary embolism from an intracardiac or paradoxical (venous) source, thrombosis caused by hypercoagulable states, and inflammation in response to specific infectious agents.1) Paclitaxel has been associated with acute myocardial infarction.2) We report a case of coronary artery thrombosis associated with paclitaxel in advanced ovarian malignancy.

Case

A 63-year-old woman was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and peritoneal carcinomatosis. A large left ovarian mass and omental cake with a large volume of ascites were noted on pelvic computed tomography (CT), and through positron emission tomography (PET), 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) uptake was noted in the left ovarian mass and omental cake. The serum CA-125 level was markedly elevated (4,290 U/mL; normal, <35 U/mL). The patient had a history of hypertension, but no history of recent infectious disease, drug use, or smoking. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a paclitaxel/carboplatin regimen was planned. First, paclitaxel was administered intravenously over 3 hours at 175 mg/m2, and after 48 hours, the administration of carboplatin was planned.

However, the day after we administered the paclitaxel, the patient complained of typical angina. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ST segment elevation in the V2-5 leads (Fig. 1A). The cardiac troponin T and creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) levels were elevated at 1.03 ng/mL (normal, <0.01 ng/mL) and 80 U/L (normal, <24 U/L), respectively. An echocardiogram demonstrated mid-anterior, septal, and apical akinesia, consistent with infarction in the left anterior descending (LAD) territory.

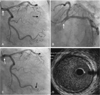

Emergency coronary angiography revealed a filling defect in the left main coronary artery and total occlusion in the distal left anterior descending coronary artery with no luminal irregularity or narrowing. We attempted to perform a detailed examination of the left main coronary artery. After we guided the catheter into the left main ostium, an additional cine view revealed that the filling defect in the left main had disappeared and the distal portion of the obtuse marginal branch of the left circumflex artery was now totally occluded. Intravascular ultrasonography (IVUS) showed no significant plaque burden or atheromatous rupture from the proximal left anterior descending artery to the left main coronary ostium. We made an unsuccessful attempt with balloon angioplasty to restore coronary blood flow (Fig. 2).

A thrombophilia work-up revealed normal or negative values for antithrombin III, protein C, protein S, lupus anticoagulant antibody, Factor VIII, anti-phospholipid IgG, Factor 5 Leiden, homocysteine, C3, and C4. Treatment with tirofiban, clopidogrel, and aspirin was planned, and a follow-up electrocardiogram was obtained (Fig. 1B). Eighteen days after the index procedure, a follow-up echocardiogram and coronary angiogram were performed. The echocardiogram showed much improvement of the previous akinesia, except at the tip of the apex of the left ventricle. The coronary angiogram showed that the occlusion of the distal obtuse marginal branch and distal left anterior descending artery had cleared (Fig. 3).

The patient is being followed in our outpatient department and has had no further cardiac symptoms.

Discussion

We present a case of coronary occlusion secondary to thrombus formation. An acute myocardial infarction (AMI) without angiographic evidence of atherosclerosis is uncommon; possible mechanisms include 1) coronary artery spasm, 2) coronary embolism from an intracardiac or paradoxical (venous) source, 3) thrombosis caused by certain hypercoagulable states, and 4) inflammation in response to specific infectious agents, such as Chlamydia pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus, and Helicobacter pylori.1) Coronary thrombosis may follow blood disorders causing hypercoagulability, oral contraceptives or estrogen-replacement therapy, endothelial dysfunction, or cigarette smoking, as well as an excess of lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] and type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1).1) Our patient had no history of recent infection, drug use, or smoking. Furthermore, there was no specific finding in the thrombophilia work-up. In the setting of malignancy, there are a few reported cases involving myocardial infarctions caused by tumor emboli, direct malignant infiltration, and non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE).3) However, an extensive search of the literature found only one report of in situ coronary thrombosis associated with malignancy in the absence of other procoagulant conditions.3) According to a recent report, malignancy itself usually does not cause coronary artery thrombosis without other hypercoagulable states.1) However, paclitaxel use has been associated with acute myocardial infarction.2)5) In our case, the coronary angiogram and IVUS showed a smooth wall without a significant stenotic lesion or plaque burden in the left main coronary artery. In the follow-up coronary angiogram, because the lesion in the culprit vessel disappeared, we presumed that the lesion was not a tumor embolus, but a thrombus. In addition, no intracardiac shunt was seen on the echocardiogram, and the regional wall motion abnormality of the left ventricle was consistent with the coronary territory. Acute myocardial infarction can be caused by a coronary thrombus in association with a myocardial bridge and slow coronary flow.6) However, the coronary angiogram of our case did not show a myocardial bridge or slow coronary flow. Except for the malignancy, the patient showed no evidence of thrombophilia based on the thrombophilia work-up, and as mentioned above, malignancy does not usually cause coronary artery thrombosis. Therefore, in this case, we considered paclitaxel to be the probable cause of the myocardial infarction due to spontaneous formation of a thrombus in the left main coronary artery. It has been seen that paclitaxel can disturb cardiac rhythm and cause cardiac ischemia and myocardial infarction.2)4) Myocardial infarction associated with paclitaxel therapy has been reported in some patients.2)5) In one of these patients, a 70% lesion with a fresh thrombus in the infarct-related artery was documented at autopsy.2) To date, the pathogenesis of myocardial infarction associated with paclitaxel is not known. However, this case raises the possibility that paclitaxel can induce coronary artery thrombosis and cause myocardial infarction. Additionally, we recommend that clinicians take extra care in ruling out myocardial infarction if chest pain occurs during paclitaxel administration.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download