Abstract

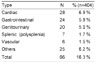

The Korean Association of Pediatric Surgeons (KAPS) performed the second nationwide survey on biliary atresia in 2011. It was a follow-up study to the first survey, which was performed in 2001 for the retrospective analysis of biliary atresia between 1980 and 2000. In the second survey, the authors reviewed and analyzed the clinical data of patients who were treated for biliary atresia by the members of KAPS from 2001 to 2010. A total of 459 patients were registered. Among them, 435 patients primarily underwent the Kasai operation. The mean age of patients who underwent the Kasai operation was 66.2±28.7 days, and 89.7% of those patients had type III biliary atresia. Only five patients (1.4%) had complications related to the Kasai operation. After the Kasai operation, 269 (61.8%) of the patients were re-admitted because of cholangitis (79.9%) and varices (20.4%). One hundred and fifty-nine (36.6%) of the patients who underwent the Kasai operation subsequently underwent liver transplantation. The most common cause of subsequent liver transplantation was persistent hyperbilirubinemia. The mean interval between the Kasai operation and liver transplantation was 1.1±1.3 years. Overall the 10-year survival rate after the Kasai operation was 92.9% and the 10-year native liver survival rate was 59.8%. We had 23 patients for primary liver transplantation without the Kasai operation. The mean age patients who underwent primary liver transplantation was 8.6±2.9 months. In summary, among the 458 Kasai-operation and liver-transplantation patients, 373 lived, 31 died, and 54 were unavailable for follow up. One-third of the patient who survived have had complications correlated with biliary atresia. In comparison with the first survey, this study showed a higher survival rate and a greater number of liver transplantation.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Flowchart showing group of study population.

1° Report; report from the pediatric surgeons who performed the Kasai operation for the reported patients.

2° Report; report from the pediatric surgeons who did not perform the Kasai operation for the reported patients, but took care of them.

LT: liver transplantation

F/U: follow up

|

| Fig. 4Patient survival rate analysis for 10 years: A) Overall survival rate after the Kasai operation; B) Comparison of the survival rate between hospitals with a large number of Kasai operations (Group I) and a small number of Kasai operations (Group II); and C) Comparison of the survival rate among six groups, five of which being hospitals (A, B, C, D, and E) with a large number of Kasai operations and the sixth (Group II) being the remainder of the hospitals (F-R).

*Group I consists of A, B, C, D and E hospitals

†Group II consists of F-R hospitals.

|

| Fig. 5Native liver survival rate analysis for 10 years: A) Overall native liver survival rate

after the Kasai operation; B) Comparison of the native liver survival rate between hospitals

with a large number of Kasai operations (Group I) and a small number of Kasai operations

(Group II); and C) Comparison of the native liver survival rate among six groups, five of

which being hospitals (A, B, C, D, and E) with a large number of Kasai operations and the

sixth (Group II) being the remainder of the hospitals (F-R).

*Group I consists of A, B, C, D and E hospitals

†Group II consists of F-R hospitals.

|

References

1. Kasai M, Suzuki S. A new operation for "non-correctable" biliary atresia: hepatic porto-enterostomy. Shujyutsu. 1959; 13:733–739. [in Japanese].

2. Choi KJ, Kim SC, Kim SK, Kim WK, Kim IK, Kim JE, Kim JC, Kim HY, Kim HH, Park KW, Park WH, Song YT, Oh SM, Lee DS, Lee MD, Lee SK, Lee SC, Chung SY, Jung SE, Jung PM, Choi SO, Choi SH, Han SJ, Huh YS, Hong J, Hwang EH. Biliary atresia in Korea: a survey by the Korean Association of Pediatric Surgeons. J Korean Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2002; 8:143–155.

3. Hartley JL, Davenport M, Kelly DA. Biliary atresia. Lancet. 2009; 374:1704–1713.

4. Weerasooriya VS, White FV, Shepherd RW. Hepatic fibrosis and survival in biliary atresia. J Pediatr. 2004; 144:123–125.

5. Statistical Database-Polulation/Household. Statistics Korea;http://kostat.go.kr.

6. Nio M, Ohi R, Miyano T, Saeki M, Shiraki K, Tanaka K. Five- and 10-year survival rates after surgery for biliary atresia: a report from the Japanese biliary atresia registry. J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 38:997–1000.

7. Petersen C, Harder D, Abola Z, Alberti D, Becker T, Chardot C, Davenport M, Deutschmann A, Khelif K, Kobayashi H, Kvist N, Leonhardt J, Melter M, Pakarinen M, Pawlowska J, Petersons A, Pfister ED, Rygl M, Schreiber R, Sokol R, Ure B, Veiga C, Verkade H, Wildhaber B, Yerushalmi B, Kelly D. European biliary atresia registries: summary of a symposium. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2008; 18:111–116.

8. Leonhardt J, Kuebler JF, Leute PJ, Turowski C, Becker T, Pfister ED, Ure B, Petersen C. Biliary atresia: lessons learned from the voluntary German registry. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 21:82–87.

9. McKiernan PJ, Baker AJ, Kelly DA. The frequency and outcome of biliary atresia in the UK and Ireland. Lancet. 2000; 355:25–29.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download