Abstract

Purpose

Surgical risks associated with the resection of osteochondroma around the proximal tibia and fibula, as well as the proximal humerus have been well established; however, the clinical presentation and optimal surgical approach for osteochondroma around the lesser trochanter have not been fully addressed.

Materials and Methods

Thirteen patients with osteochondroma around the lesser trochanter underwent resection. We described the chief complaint, duration of symptom, location of the tumor, mass protrusion pattern on axial computed tomography image, tumor volume, surgical approach, iliopsoas tendon integrity after resection, and complication according to the each surgical approach.

Results

Pain on walking or exercise was the chief complaint in 7 patients, and numbness and radiating pain in 6 patients. The average duration of symptom was 19 months (2–72 months). The surgical approach for 5 tumors that protruded postero-laterally was postero-lateral (n=3), anterior (n=1), and medial (n=1). All 4 patients with antero-medially protruding tumor underwent the anterior approach. Two patients with both antero-medially and postero-laterally protruding tumor received the medial and anterior approach, respectively. Two patients who underwent medial approach for postero-laterally protruded tumor showed extensive cortical defect after resection. One patient who received the anterior approach to resect a large postero-laterally protruded tumor developed complete sciatic nerve palsy, which was recovered 6 months after re-exploration.

Conclusion

For large osteochondromas with posterior protrusion, we should not underestimate the probability of sciatic nerve compression. When regarding the optimal surgical approach, the medial one is best suitable for small tumors, while the anterior approach is good for antero-medial or femur neck tumor. For postero-laterally protruded large tumors, posterior approach may minimize the risk of sciatic nerve palsy.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1(A) A 20-year-old man with tumors protruding postero-laterally complained of numbness and radiating pain on prolonged sitting position (case 3). (B) Axial magnetic resonance imaging shows antero-medially protruding tumor. (C) The tumor was excised via the medial approach. A large medial cortical defect was confirmed, postoperatively. (D) To prevent fractures, internal fixation and autogenous bone graft was performed at 1 week from the index operation. |

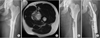

| Figure 2(A) Plain radiograph shows a huge osteochondroma in the lesser trochanter and femur neck (case 6). (B) Axial compiuted tomography demonstrates a mass protruding both antero- and postero-medially. (C) Postoperative radiograph shows excised tumor through the anterior approach, however, the patient developed complete sciatic nerve palsy. (D) At 18 hours from the identification of palsy, re-exploration of sciatic nerve was done. The continuity of the nerve was well preserved; however, it showed scarring of 5 cm due to a long-term compression by the tumor. |

References

1. Murphey MD, Choi JJ, Kransdorf MJ, Flemming DJ, Gannon FH. Imaging of osteochondroma: variants and complications with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000; 20:1407–1434.

2. Stieber JR, Dormans JP. Manifestations of hereditary multiple exostoses. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005; 13:110–120.

3. de Souza AM, Bispo Júnior RZ. Osteochondroma: ignore or investigate? Rev Bras Ortop. 2014; 49:555–564.

4. Saglik Y, Altay M, Unal VS, Basarir K, Yildiz Y. Manifestations and management of osteochondromas: a retrospective analysis of 382 patients. Acta Orthop Belg. 2006; 72:748–755.

5. Wirganowicz PZ, Watts HG. Surgical risk for elective excision of benign exostoses. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997; 17:455–459.

6. Eschelman DJ, Gardiner GA Jr, Deely DM. Osteochondroma: an unusual cause of vascular disease in young adults. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995; 6:605–613.

7. Makhdom AM, Jiang F, Hamdy RC, Benaroch TE, Lavigne M, Saran N. Hip joint osteochondroma: systematic review of the literature and report of three further cases. Adv Orthop. 2014; 2014:180254.

8. Yu Y, Sun X, Song X, Tian Z, Zhou Y. A novel surgical approach for the treatment of tumors in the lesser trochanter. Exp Ther Med. 2015; 10:201–206.

9. Li M, Luettringhaus T, Walker KR, Cole PA. Operative treatment of femoral neck osteochondroma through a digastric approach in a pediatric patient: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012; 21:230–234.

10. Göbel V, Jürgens H, Etspüler G, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor volume in localized Ewing's sarcoma of bone in children and adolescents. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1987; 113:187–191.

11. Weinstein SL, Ponseti IV. Congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979; 61:119–124.

12. Ludloff K. The open reduction of the congenital hip dislocation by an anterior incision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1913; 210:438–454.

13. Moore AT. The moore self-locking Vitallium prosthesis in fresh femoral neck fractures: a new low posterior approach (the southern exposure). AAOS Instr Course Lect. 1959; 16:309–321.

15. Kong CB, Lee KY, Cho SH, et al. Rupture of a brachial artery caused by a humeral osteochondroma. J Korean Orthop Assoc. 2013; 48:297–301.

16. Ramos-Pascua LR, Sánchez-Herráez S, Alonso-Barrio JA, Alonso-León A. Solitary proximal end of femur osteochondroma. An indication and result of the en bloc resection without hip luxation. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2012; 56:24–31.

17. Kim HJ, Kim SS, Kim CH, Kim HJ. Sciatic nerve compression secondary due to ischial tuberosity osteochondroma. J Korean Hip Soc. 2012; 24:65–69.

18. Yu K, Meehan JP, Fritz A, Jamali AA. Osteochondroma of the femoral neck: a rare cause of sciatic nerve compression. Orthopedics [Internet]. 2010. cited 2010 Aug 11. 2010;33. DOI: 10.3928/01477447-20100625-26. Available from: http://www.healio.com/orthopedics/journals/ortho/2010-8-33-8/%7Bd3161a80-dff0-42b3-ad54-bb3eb266cd00%7D/osteochondroma-of-the-femoral-neck-a-rare-cause-of-sciatic-nerve-compression.

19. Bottner F, Rodl R, Kordish I, Winklemann W, Gosheger G, Lindner N. Surgical treatment of symptomatic osteochondroma. A three- to eight-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003; 85:1161–1165.

20. Tschokanow K. 2 cases of osteochondroma of the femur neck. Beitr Orthop Traumatol. 1969; 16:751–752.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download