Abstract

Posttraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) is the most serious complication after fracture dislocation of the femoral head. The rate of this complication was reported to range from 1.7% to 40%. Although the development of posttraumatic osteonecrosis normally occurs within 2 years of injury, there are some reports of the late development ONFH. The authors encountered a case of posttraumatic ONFH that developed after 9 years of a Pipkin type I fracture dislocation. The patient was treated by modified transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy. We report this rare case with a review of the relevant literatures.

Femoral head fractures due to posterior hip fracture dislocation-also called Pipkin fractures-are relatively rare, but injuries are often severe. The fracture itself and posttraumatic changes, such as, heterotopic ossification, secondary osteoarthritis or osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH), may eventually restrict hip functions and cause permanent disability, even in young patients.1) Among these complications, ONFH is the most devastating complication and has been reported to occur in 1.7% to 40% of cases.2)

Foy and Fagg3) found that the radiographic changes of ONFH usually develop within 2 years of injury; a figure is generally accepted. However, a small number of reports have issued concerning delayed occurence of ONFH, 8 years after hip posterior dislocation,4) 15 years after femoral neck fracture,5) and even at 28 years after femoral neck fracture.6) There is no literature available about delayed ONFH after femoral head fracture and posterior dislocation.

Here, we describe our experience of a case of posttraumatic ONFH of the femoral head, which occurred 9 years after a Pipkin type I fracture dislocation of the left hip, and was treated by modified transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy.7)

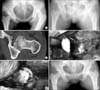

A 31-year-old woman presented with complaint of left hip pain of two months duration. She had injured a left femoral head fracture and posterior dislocation 9 years ago by an accident while driving a car, and had been treated by open reduction and internal fixation with three screws (Herbert's screws; Zimmer Inc., Warsaw, IN, USA; 4.5×30 mm) via a Smith-Petersen anterior approach. Although the fragement was located below the fovea centralis (Pipkin type I), it was intraarticular and relatively a large size, we decided to reduce it anatomically and fix it (Fig. 1). At that time, closed reduction of the dislocation was performed within six hours after injury. But for the treatment of a concomitant lung injury (bilateral hemothorax), fixation of the head fragment were delayed until seven days after injury. After surgery, she was followed-up for four years.

In nine years after injury, the patient complained of a left hip pain for 2 months which was getting worse recently. A physical examination revealed a limp and a mildly restricted range of motion of the left hip joint (flexion 110°, extension 0°, internal rotation 25°, external rotation 40°, abduction 40°, adduction 30°). The Patrick test was positive.

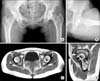

Radiographs of left hip showed bony union with screws in situ without joint space narrowing or other signs of osteoarthritis. There was no evidence of femoral head collapse (Fig. 2A, 2B). Magnetic resonance imagimg of the hip showed small area of signal change in the anterosuperior portion of the femoral head with positive double line sign (Fig. 2C, 2D). The radiologic diagnosis of ONFH was confirmed by two independent radiology specialists.

Extensive investigations for risk factors of ONFH were performed. She had no history of taking steroids for therapy or any other purpose, denied alcohol abuse; her serum ethanol level was low and her carboxy-deficient-transferrin levels were normal, which ruled out chronic alcoholism. The findings of tests for systemic thrombophilia were normal or negative; these included, blood clotting time, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, protein-C and protein-S levels, and resistance to activated-protein-C. No blood cell disorders associated with blood vessel occlusion were found, and her serum bilirubin level was normal. The findings of tests for antibodies associated with connective tissue disease were normal or negative, these included antinuclear antibody, ds-DNA, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.

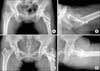

Because of the absence of any risk factor other than a history of trauma, we diagnosed posttraumatic ONFH which developed by previous injury of femoral head fracture dislocation. Because the patient was young and active, modified transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy7) was planned to preserve the femoral head (Fig. 3).

At postoperative three years of follow-up, she had no pain or limp and could sit cross legged and squat (Fig. 4). The patient provided informed consent that case data could be submitted for publication.

The rate of posttraumatic ONFH after hip posterior dislocation has been reported to range from 1.7% to 40%.2) The most significant clinical factor of ONFH in this setting is the length of time a hip remains dislocated. If a hip is reduced within the confines of the acetabulum within 6 hours of dislocation, the rate of ONFH has been reported to decrease to 0% to 10%.2) The causes of posttraumatic ONFH are thought to be mainly two. The cervical vessels to the head and the contributions from the ligamentum teres are damaged at the time of injury. Secondarily, an ischemic insult to the femoral head while it is dislocated affects outcome.2)

In 1962, Brav8) reported on 189 patients who developed ONFH after reduction for a traumatic hip dislocation. Of these, 98% became symptomatic within 1 year and the remaining 2% became symptomatic between 1 and 5 years. It was also reported that the radiographic changes of ONFH develop within 2 years of injury. Accordingly, it has been recommended that medico-legal reporting should be undertaken 18-24 months from the time of injury.3)

However, Cash and Nolan4) reported a case of ONFH of the femoral head that occurred at 8 years after posterior hip dislocation. The hip was reduced within 6 hours of injury and there was no evidence of necrosis during 3 years of follow-up. However, 5 years later, the patient presented with hip pain and was treated by total hip arthroplasty. Not surprisingly, the authors recommended that additional consideration be given to length of follow-up and medico-legal reporting after hip dislocation.

Kisielinski et al.5) reported a case of ONFH of femoral head 15 years after a transcervical femoral neck fracture in a woman with a 20-year history of daily inhaled glucocorticoid therapy for chronic bronchitis, and recommended that caution be exercised in patients on low-dose inhaled glucocorticoids, particularly those with internal fixation devices implanted to treat femoral neck fracture. It was concluded that the low-dose inhaled glucocorticoid therapy and femoral neck fracture combination may cause osteonecrosis in the long-term. In our case, the absence of steroid use and alcohol abuse and laboratory findings indicated no blood cell disorder, connective tissue disease, or any other risk factor of ONFH, other than a trauma history. The initial posterior dislocation in this patient was reduced within 6 hours and femoral head fracture fixation was done using the Smith-Petersen approach. Stannard et al.9) undertook an odds ratio analysis on different surgical approaches to femoral head fracture dislocation, and found that the Kocher-Langenbeck posterior approach was associated with a 3.2 fold higher rate of ONFH development than the Smith-Petersen approach.

Some surgeons may question the prudence of internally fixing a head fragment which is infra foveal. We believe that the fixation was justified and essential because the fragment was large and the hip was unstable without its fixation.10)

Several methods can be used to treat early stage, precollapse lesions of the femoral head, e.g., core decompression, nonvascularized bone graft, vascularized bone graft, or osteotomy. Fortunately, unlike ONFH secondary to systemic illness or medication, or idiopathic ONFH, posttraumatic ONFH may be highly localized, and thus, it is more amenable to osteotomy than global ONFH.2) Accordingly, in our patient, after considering her age, the location and the size of the ONFH, osteotomy was considered as the best treatment option.

Rotational osteotomy was first performed by Sugioka in Japan in 1972 and first reported in the English literature in 1978. It involves rotating the femoral head around the longitudinal axis of the neck to remove the area of necrosis from weight-bearing and transferring shear forces to the healthier posterior cartilage of the femoral head.7) Our center has performed transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy since 2003 and the results were good.7) In the described patient, the rotation involved a movement of almost 90 degrees anteriorly, and thus, the anterosuperior osteonecrosis was relocated anteroinferiorly. The osteotomy site united at 2 months postoperatively.

Summarizing, ONFH can develop 9 years after femoral head fracture and posterior dislocation, and thus, careful serial follow-up is required. Furthermore, patients should be counseled about this complication and advised to report any hip pain, so that diagnosis and treatment can be initiated at the earliest opportunity-before collapse or arthrosis develops. In the present case, the patient underwent modified transtrochanteric osteotomy and good results were achieved. Accordingly, we recommend that the described modified transtrochanteric osteotomy be considered as a good treatment option in such cases.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

(A) Anteroposterior radiograph of both hips show a Pipkin type I fracture dislocation. (B) Radiograph taken after a closed reduction. (C) Computed tomography scan of the left hip after reduction shows a large anterior bony fragment. (D) Intraoperative photograph shows a relatively large fragment involving the anteroinferior portion of the femoral head. (E) Intraoperative photograph after fixation of the fragment. (F) Radiograph taken after open reduction and fixation with three-screws.

Figure 2

Anteroposterior (A) and femoral head lateral (B) radiographs taken 9 years after injury show good maintenance of the joint space and bony union without subchondral fracture or other sign of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. T1-weighted magnetic resonance imagimg axial (C) and coronal (D) view show a small region of the osteonecrosis anteriosuperior of the femoral head (white arrows).

References

1. Henle P, Kloen P, Siebenrock KA. Femoral head injuries: Which treatment strategy can be recommended. Injury. 2007; 38:478–488.

2. Kain MSH, Tornetta P III. Hip dislocations and fractures of the femoral head. In : Rockwood CA, McQueen MM, editors. Rockwood and Green's fractures in adults. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2010. p. 1524–1560.

3. Foy MA, Fagg PS. Medicolegal reporting in orthopaedic trauma. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone;2003. p. 239–243.

4. Cash DJ, Nolan JF. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head 8 years after posterior hip dislocation. Injury. 2007; 38:865–867.

5. Kisielinski K, Niedhart C, Schneider U, Niethard FU. Osteonecrosis 15 years after femoral neck fracture and long-term low-dose inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Joint Bone Spine. 2004; 71:237–239.

6. Strömqvist B. The longest delay between femoral neck fracture and femoral head collapse? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1985; 104:125–128.

7. Yoon TR, Abbas AA, Hur CI, Cho SG, Lee JH. Modified transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy for femoral head osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008; 466:1110–1116.

8. Brav EA. Traumatic dislocation of the hip army experience and results over a twelve-year period. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962; 44:1115–1134.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download