This article has been corrected. See "Erratum: Lipoma-like Liposarcoma with Osteosarcomatous Dedifferentiation of the Chest Wall: A Case Report" in Volume 16 on page 81.

Abstract

We report a case of liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation of the chest wall in a 58-year-old man, which had been initially mistaken as myositis ossificans. CT and MRI demonstrated a soft tissue mass consisting of two components: a non-lipomatous area with amorphous calcification/ossification and a well-encapsulated fatty component. Based on local excision in the non-lipomatous area, myositis ossificans was initially diagnosed. As the mass was gradually enlarging, however, wide excision including the fatty component was performed and histological assessment revealed lipoma-like, well-differentiated liposarcoma with high-grade osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation. Here, we describe the radiological-pathological features of this rare neoplasm.

Liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation is a very rare condition; only eighteen cases have been reported thus far worldwide (1-9). Among them, there are only four radiologic reports to date (1, 6-8). Most caseshave occurred in the retroperitoneum or lower extremities, and to our knowledge, there has been no report of tumor developed in the chest wall.

Although nonfatty areas with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation could be mistaken as myositis ossificans or extraosseous osteosarcoma radiologically or pathologically, there have been very few reports focused on this issue. We describe a 58-year-old male patient who presented with a case of liposarcoma with high-grade osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation located in the chest wall, which waspreviously misdiagnosed as myositis ossificans, along with radiologic and pathologic findings.

The patient was a 58-year-old man in whom a large calcified mass had been found incidentally by chest radiograph performed on routine check-up in 2007. He received local excision at an outside hospital 2 years later, where a diagnosis of myositis ossificans was made. Next year, he visited our institution due to tumor re-growth at the excision site.

His chief complaint was a large mass in his left chest wall, which had undergone a growth spurt during the several months after local excision, causing discomfort in the left lateral decubitousposition. His past medical history was otherwise unremarkable. On physical examination, the hard mass measuring about 10×15 cm in size was palpated without tenderness.

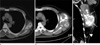

Computed tomography with contrast enhancement taken at the time of referral (Fig. 1) disclosed a well-defined, lobulated soft tissue mass with central, irregular, dense and amorphous calcification/ossification. This chest wall lesion did not have any relation to adjacent ribs, intercostal muscles, or pleura. Inferiorly apposing the proximal component of the mass was a smaller cap-like component with fat density and internal fine septae There was significant enlargement of the lesion compared with the former non-enhanced CT performed after local excision in 2009 (Fig. 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large extraskeletal mass with heterogeneous signal intensity containing cystic spaces on T2-weighted images, calcified/ossified areas with dark signal intensity on allsequences, and nonspecific solid components (Fig. 2). Heterogeneous enhancement the solid component was noted after intravenous administration of gadolinium-based contrast agent. The distal portion of the mass showed fat signal intensity on T1-weighted images and short inversion time inversion recovery (STIR) images. A similar but less prominent finding was noted along the proximal extent of the mass. There was no enhancing solid portion within the inferior fatty component.

Based on clinical and radiological features, an initial diagnosis of a soft-tissue osteosarcoma was suggested because the fatty component was so underappreciated that it was dismissed as normal adjacent fat. The patient underwent wide excision and at surgical inspection, the tumor appeared to consist of two distinct components - a firm and fleshy soft tissue mass in which the cut surface showed cysts, calcification/ossification, necrosis and hemorrhage and a yellowish fatty cap distal to the larger firm mass.

Histologically, the fatty cap of the inferior tumor area was consistent with lipoma-like, well-differentiated liposarcoma with atypical stromal cells (Fig. 3). The larger firm part of the tumor showed osteoid matrix and irregular woven bone formations by malignant spindle cells, while osteosarcoma with aneurismal bone cyst-like changes was also found. Final diagnosis based on the entire specimen was dedifferentiated liposarcoma with a high-grade osteosarcomatous component rather than a soft-tissue osteosarcoma.

"Dedifferentiation" of sarcoma is initially described in chondrosarcoma. Histologically distinctive borderline or low-grade malignant neoplasm is juxtaposed to a high-grade, histologically different sarcoma in this condition. Evans et al. introduced the term "dedifferentiated liposarcoma" in 1979 (10) to describe a lesion with two different components - a well-differentiated liposarcoma juxtaposed to a high-grade sarcoma, most commonly a malignant fibrous histiocytoma or fibrosarcoma. Dedifferentiation into various other histology, such as rhabdomyosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and osterosarcoma, is reported in 10% of cases of liposarcomas (3). Most reported dedifferentiated liposarcoma cases were located in the deep soft tissues of the extremity and retroperitoneum (1, 2, 4, 7-9).

Previously reported 18 cases of dedifferentiated liposarcoma with an osteosarcomatous component are summarized in Table 1 (1-9). The retroperitoneam and thigh were the most common sites, followed by the buttock area, axilla and pleura. To our knowledge, there has been no report of a case located in the chest wall. The age range of these reported cases was from 47 to 78 years (average, 65 years) with the male to female ratio being almost equal. The average size of the tumors in 13 cases for which data were available was 19.7 cm in diameter.

Osteogenic potential in well-differentiated/dedifferentiated liposarcoma is sporadically recorded in the literature. In most accounts (1, 4, 6-8), the osseous components were characterized by immature lace-like osteoid production, high cellularity, high nuclear grade, brisk mitotic activity, and/or necrosis, and therefore histologically resembled conventional high-grade osteosarcomas. In this condition, liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation can also be mistaken as myositis ossificans or malignant transformation of myositis ossificans to extraskeletal osteosarcoma, a condition that is extremely rare and diagnosed mainly on the basis of repeated morphologic examinations. Generally, a zonation pattern and prominent osteoblastic rimming of myositis ossificans can help distinguish it from liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation. According to Yoshida et al. (9), 1 of 9 cases was mistaken for myositis ossificans until its malignant nature was noted at reccurence as a conventional lipoma-like, well-differentiated liposarcoma 2 years later. The authors speculated that such misinterpretation can be caused by the deceptively bland appearance of fibroosseous components or small biopsy specimens. This clinical setting is similar to our case in that recurrence suggested malignancy.

While calcification/ossification is a documented feature of lipomatous tumours on radiographs, there would be potential difficulty in diagnosing osseous metaplasia in well-differentiated liposarcoma. On pathologic evaluation of osseous metaplasia in well-differentiated liposarcoma, there have been no osteoblastic proliferation or atypical cells in the foci of osteoid deposition according to previous studies. On the contrary, our case not only showed extensive ossification/calcification on imaging studies, but also had immature clusters of spindle cells in a pattern characteristic of osteosarcoma on microscopic examination. Suspicious characteristics of the lesion suggesting dedifferentiation can be the location, recurrent nature and osteoid formation of the tumor.

Most cases of dediffernetiated liposarcoma have large lipomatous portions with smaller nonlipomatous portions. In our case, however, the nonlipomatous component was larger than the lipomatous component as in the case reported by Yu et al. (7). The lipomatous component, which is important in radiological diagnosis, could be overlooked during diagnosis of this conditon. In our case, because of the extensive ossification and dominating size of the dedifferentiated component juxtaposed to the well-differentiated liposarcoma on imaging, the erroneous diagnosis of extraskeletal osteosarcoma was suggested before surgery. However, a well-differentiated liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation should have been considered given the fatty areas inferiorly connected to the large nonlipomatous mass.

This case report highlights the importance of recognizing the fatty component in this underappreciated subtype of well-differentiated/dedifferentiated liposarcoma. All well-differentiated liposarcomas of deep soft tissues should be considered to be at risk of dedifferentiation to high-grade tumors (1, 3), although that risk varies with the location and duration of disease. It is also worth noting that the dedifferentiated component of the liposarcoma can vary in size from small to large and the ossification or mineralization can be focal or quite extensive. If not, the fibroosseous component may be confused with benign metaplasia such as myositis ossificans, or the lipomatous component may be so inconspicuous that it may be dismissed as normal fat, and such misinterpretation may have the potential to result in suboptimal treatment.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Lipoma-like liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation of the chest wall in a 58-year-old man. Non-enhanced chest CT scan (a) demonstrates a soft tissue mass with discrete central ossification/calcification at his lateral chest wall. On follow-up CT scan taken after 9 months from (a), an axial image (b) demonstrates significant increase in the tumor size. Coronal reformatted imaging (c) shows an elongated bimorphic mass with a length of 18 cm. The larger upper portion (arrows) of the mass shows non-lipomatous soft tissue attenuation containing multiple amorphous areas of calcification/ossification. The fatty lower portion (arrowhead) shows no definite solid component. |

| Fig. 2Lipoma-like liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation of the chest wall in a 58-year-old man. Coronal T1-weighted image (a) of the chest reveals that the lower portion of the tumor is of homogenous high signal intensity (arrowhead), consistent with fat, whereas the larger upper portion (asterisk) shows heterogeneous intermediate and low signal intensity with subtle high signal intensity of fat (arrows) in the periphery. Corresponding STIR image (b) and fat-saturated coronal T1-weighted image (c) after intravenous gadolinium administration confirm the fatty nature of the lower portion (arrowheads) as well as the periphery (arrows) of the upper portion of the tumor by nulling the signal return. There is no enhancement in the fatty lower portion of the tumor other than thin capsular enhancement. The upper portion of the tumor (asterisk) shows heterogeneous enhancement and heterogeneous T2 signal from bright high signal to dark low signal representing cystic changes and tumor mineralization, respectively. |

| Fig. 3(a) Photomicrograph (original magnification, ×100; hematoxylin-eosin stain) of the lipomatous portion of the tumor shows predominantly lipocytes admixed with scattered atypical stromal cells (arrows) with irregular, hyperchromatic nuclei. (b) Photomicrograph (original magnification, ×40; hematoxylin-eosin stain) of the osteosarcomatous component demonstrates dense trabecular bony spicules. (c) In a magnified view of (b) (×200), there are malignant spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei (arrows) with osteoid and woven bone formation. |

References

1. Ippolito V, Brien EW, Menendez LR, Mirra JM. Case report 797: "Dedifferentiated" lipoma-like liposarcoma of soft tissue with focal transformation to high-grade "sclerosing" osteosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1993. 22:604–608.

2. Evans HL, Khurana KK, Kemp BL, Ayala AG. Heterologous elements in the dedifferenatiated component of dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994. 18:1150–1157.

3. Henricks WH, Chu YC, Goldblum JR, Weiss SW. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 155 cases with a proposal for an expanded definition of dedifferentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997. 21:271–281.

4. Yamamoto T, Matsushita T, Marui T, et al. Dedifferenatiated liposarcoma with chondrobalstic osteosarcomatous dedifferenatiation. Pathology International. 2000. 50:558–561.

5. Takanami I, Imamura T. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma of the pleura: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005. 313–316.

6. Toms A, White LM, Kandel R, Bell R. Low-grade liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation: radiological and histological features. Skeletal Radiol. 2003. 32:286–289.

7. Yu L, Fung S, Hojnowski L, Damron T. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma of soft tissue with high-grade osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation. Radiographics. 2005. 25:1082–1086.

8. Toshiyasu T, Ehara S, Yamaguchi T, Nishida J, Shiraishi H. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma of the retroperitoneum with osteosarcomatous component: report of two cases. Clinical Imaging. 2009. 33:70–74.

9. Yoshida A, Ushiku T, Motoi T, Tatsuhiro T, Fukayama M, Tsuda H. Well-differentiated liposarcoma with low-grade osteosarcomatous component. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010. 34(9):1361–1366.

10. Evans HL. Liposarcoma: a study of 55 cases with reassessment of its classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 1979. 3:507–523.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download