Abstract

Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD) is an autosomal recessive hereditary metabolic disorder of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. It is characterized by hypoketotic hypoglycemia, hyperammonemia, seizure, coma, and sudden infant death syndrome-like illness. The most frequently isolated mutation in the acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium-chain (ACADM) gene of Caucasian patients with MCADD is c.985A>G, but ethnic variations exist in the frequency of this mutation. Here, we describe 2 Korean pediatric cases of MCADD, which was detected during newborn screening by tandem mass spectrometry and confirmed by molecular analysis. The levels of medium-chain acylcarnitines, including octanoylcarnitine (C8), hexanoylcarnitine (C6), and decanoylcarnitine (C10), were typically elevated. Molecular studies revealed that Patient 1 was a compound heterozygote for c.449_452delCTGA (p.Thr150ArgfsX4) and c.461T>G (p.L154W) mutations, and Patient 2 was a compound heterozygote for c.449_452delCTGA (p.Thr150ArgfsX4) and c.1189T>A (p.Y397N) mutations. We detected asymptomatic patients with MCADD by using a newborn screening test and confirmed it by ACADM mutation analysis. This report presents evidence of the biochemical and molecular features of MCADD in Korean patients and, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the c.461T>G mutation in the ACADM gene.

Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD; OMIM 607008) is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) is a homotetramer and shows its highest activity with octanoyl-CoA. Clinical symptoms are variable, including hypoketotic hypoglycemia, hyperammonemia, gastritis, lethargy, seizure, coma, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)-like illness. In about 20% of the patients, sudden death occurs at the first presentation of the disease [1]. Other affected individuals may remain without any symptoms for several years [2, 3]. The duration of the onset of the symptoms can range between 2 days to 6.5 yr, and the symptoms are triggered by catabolic stresses such as infection and prolonged fasting [1]. To prevent catabolic stress, patients are made to consume a carbohydrate-rich diet and carnitine supplements and prevented from fasting.

MCADD is the most frequently diagnosed clinical defect of fatty acid metabolism in Caucasians. The frequency of the disease ranges from 1:10,000 to 1:30,000 in the United States, and it is detected during newborn screening using tandem mass spectrometry [2, 4-6]. However, this disorder is relatively rare in Asian populations. Although the frequency of MCADD detection has increased after the introduction of neonatal newborn screening with tandem mass spectrometry, including acylcarnitine analysis, and with the increase of awareness of the disorder, it is still rare in Asians. The incidence of MCADD is 1:51,000 in the Japanese population, and there were no cases of the disorder among the 79,179 newborns screened in Korea [7, 8]. To date, 1 Korean and 11 Japanese patients have been confirmed to be positive for MCADD by molecular analysis [9-12].

The human ACADM gene is located on chromosome 1p31 and spans 44 kb. It contains 12 exons encoding a mature protein of 396 amino acids (43.6 kDa) [13]. The mutation frequency in the ACADM gene shows ethnic variation. In Caucasian patients with MCADD, a common c.985A>G mutation was identified in about 80-90% of the mutant alleles [2, 14]. However, the results of 2 previous reports indicate that c.449_452delCTGA is the most common disease-causing ACADM mutation identified in Asians [9, 10, 12]. In this report, we describe 2 Korean pediatric patients with MCADD that was detected during newborn screening tests by tandem mass spectrometry. Molecular studies revealed 2 genetic variations in each patient, and a novel ACADM mutation was identified.

A female patient was born at a gestational age of 37 weeks and 5 days by spontaneous vaginal delivery, and her weight at birth was 2.86 kg. She did not have any clinical manifestations of metabolic disorders. However, MCADD was suspected on the basis of the results of newborn screening tests, and the patient was referred to our hospital.

On postnatal day 23, plasma amino acid analysis showed an elevated methionine level of 77 µmol/L (reference interval (RI), 22.9-41.7 µmol/L), elevated tyrosine level of 217 µmol/L (RI, 49.1-88.9 µmol/L), and elevated ornithine level of 227 µmol/L (RI, 39.4-130.6 µmol/L). Plasma acylcarnitine profile revealed an accumulation octanoylcarnitine level of 2.19 µmol/L (RI, ≤0.5 µmol/L) and hexanoylcarnitine level of 0.78 µmol/L (RI, ≤0.44 µmol/L), and these findings are considered to be typical of MCADD (Table 1). The levels of total and free carnitines were within the normal range. Hexanoylglycine, suberylglycine, and 5-hydroxycaproic acid were detected in urine organic acid analysis. Other laboratory investigations showed a normal total bilirubin level of 147.06 µmol/L (RI, 17.1-205.2 µmol/L) and AST level of 46 U/L (RI, 16-74 U/L), and slightly elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level of 335 U/L (RI, 40-300 U/L). Ammonia (75.22 µmol/L; RI, 14.68-38.17 µmol/L) and lactate levels (4.6 mmol/L; RI, 0.6-3.2 mmol/L) were elevated. The patient was diagnosed with MCADD on the basis of the above findings and was administered carnitine supplements with frequent food intake.

Two months later, the plasma amino acid levels had normalized; however the octanoylcarnitine level remained elevated at 2.59 µmol/L on acylcarnitine analysis. Urine organic acid analysis showed an elevated suberylglycine level of 3.52 mmol/molCr (RI, not detected), suberic acid level of 12.82 mmol/molCr (RI, <10.1 mmol/molCr), and sebacic acid level of 7.66 mmol/molCr (RI, <1.4 mmol/molCr); these analyses also showed peaks for octanedioic acid and decenedioic acid. Liver function tests revealed normal total bilirubin and AST levels; however, ALP, ammonia, and lactate levels remained as high as before. The pediatric patient has been growing normally and has been continuously followed without apparent problems.

A male patient was born at a gestational age of 39 weeks and 5 days by spontaneous vaginal delivery, and his weight at birth was 3.74 kg. There was no clinical evidence of metabolic disorder at the time of birth. However, MCADD was suspected on the basis of the results of newborn screening with tandem mass spectrometry, and the patient was referred to our hospital at 10 days of age.

Amino acid analysis showed that hydroxyproline (99.4 µmol/L; RI, 0-91 µmol/L) and proline (769.9 µmol/L; RI, 110-417 µmol/L) levels were slightly elevated. Plasma acylcarnitine analysis showed an elevated octanoylcarnitine level of 7.51 µmol/L, hexanoylcarnitine level of 1.28 µmol/L, and decanoylcarnitine level of 0.62 µmol/L (RI, ≤0.51 µmol/L) at 14 days of age. Urine organic acid analysis revealed elevations in hexanoylglycine (3.30 mmol/molCr; RI, not detected) and suberylglycine (2.46 mmol/molCr) levels. Other abnormal laboratory findings included elevated ALP levels (532 U/L; RI, 40-300 U/L), hyperphosphatasemia (2.65 mmol/L; RI, 1.55-2.61 mmol/L), hyperammonemia (74.05 µmol/L), and a lactate level (3.2 mmol/L) that was the upper limit of the normal value. The patient was suspected to have MCADD on the basis of these biochemical findings.

At 17 days of age, the patient developed fever, cough, rhinorrhea, and dyspnea due to a respiratory syncytial virus infection and received conservative treatment. He recovered fully and was discharged.

At 44 days of age, plasma amino acid analysis revealed non-specific elevations in the levels of glutamic acid, cystine, and proline. Plasma acylcarnitine analysis showed abnormalities when compared with the control profiles, with elevations in the levels of octanoylcarnitine (1.66 µmol/L) and hexanoylcarnitine (0.53 µmol/L) and normal levels of total and free carnitine levels. Urine hexanoylglycine, suberylglycine, suberic acid, and sebacic acid levels were elevated at 3.05 mmol/molCr, 2.33 mmol/molCr, 16.00 mmol/molCr, and 5.36 mmol/molCr, respectively, and peaks of 5-hydroxycarproic acid, 7-hydroxyoctanoic acid, cis-4-octenedioic acid, and decenedioic acid were observed in urine organic acid analysis. The results of liver function tests were almost normal, but hyperammonemia (58.25 µmol/L) and lactic acidosis (3.9 mmol/L) persisted.

At 56 days of age, the plasma octanoylcarnitine level still remained elevated (1.52 µmol/L) and the levels of hexanoylglycine and suberylglycine were observed to be elevated at 1.38 mmol/molCr and 1.25 mmol/molCr, respectively, in urine organic acid analysis. The pediatric patient has been growing normally so far and is under outpatient follow-up.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood leukocytes of both patients and the parents of Patient 1 by using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). All exons of the ACADM gene were amplified by PCR on a thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with primer pairs designed by the authors. Direct sequencing was performed with the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit on an ABI Prism 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequences were analyzed using the Sequencher program (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and were compared to the reference sequences. The numbering of nucleotide positions was done according to the ACADM cDNA sequence, and the Gen-Bank accession number was NM 000016.4. Sequence variation was described according to the recommendations of the Human Genome Variation Society (http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen).

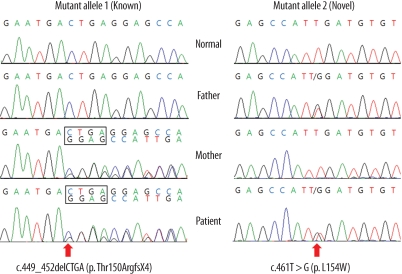

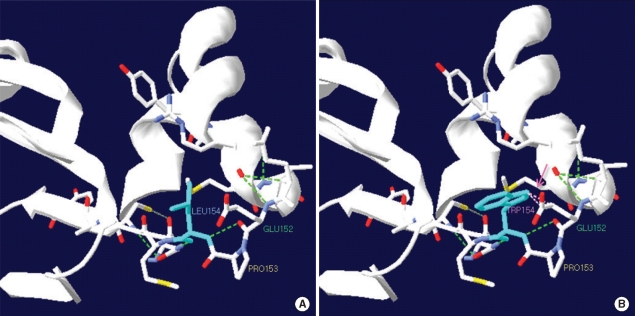

In Patient 1, sequence analysis of the ACADM gene revealed a known mutation, c.449_452delCTGA (p.Thr150-ArgfsX4), in exon 6 and a previously unrecognized mutation in the same exon, a T to G transversion at position 461 that would alter a leucine to tryptophan at amino acid position 154 (p.L154W) (Fig. 1). Sequencing analysis of Patient 1's parents showed that the mother was heterozygous for the c.449_452delCTGA mutation, and the father was heterozygous for the c.461T>G mutation. A control study conducted using the exon 6 targeted sequencing analyses in 340 alleles of 170 healthy subjects did not reveal any carriers of the c.461T>G mutation. The novel mutation is associated with major amino acid substitutions, and this mutation is likely to be the cause of the disorder. Using the SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-Pdb Viewer, the protein structure was analyzed: the novel mutation was predicted to cause no significant structural destruction, but it produced a side-chain clash that could result in backbone shifts in order to avoid clashes between amino acid side chains and its local backbone (Fig. 2).

In Patient 2, direct sequencing revealed that the patient was a compound heterozygote for 2 known mutations. The mutations were a 4-bp deletion at position 449 to 452 in exon 6 (p.Thr150ArgfsX4), identical to the mutation in Patient 1, and a T to A transversion at position 1189 in exon 11, which resulted in a change from tyrosine to asparagine, c.1189T>A (p.Y397N).

To identify patients with fatty acid oxidation disorders, neonatal screening tests with tandem mass spectrometry, including acylcarnitine analysis and confirmatory mutation analysis are essential. The high levels of hexanoylcarnitine, octanoylcarnitine, and decanoylcarnitine and the octanoylcarnitine/decanoylcarnitine ratio can be used to differentiate of MCADD patients from healthy individuals and patients with other disorders [15]. Urine organic acid analysis of MCADD patients revealed peaks of medium-chain dicarboxylic acids, hexanoylglycine, and suberylglycine. In both our patients, significant elevations of medium-chain acylcarnitines, especially octanoylcarnitine, were observed, and hexanoylglycine and suberylglycine were detected in urine organic acid analysis. These findings are typical for patients with MCADD.

More than 70 mutations have been identified in the ACADM gene, and the most common type is a missense mutation. The most frequently detected mutation involves an A to G transition at nucleotide position 985 (c.985A>G), which results in the substitution of glutamate for lysine at amino acid position 329 (p.K329E). The distribution of the c.985A>G mutation is known to vary according to ethnicity and other factors. According to previous publications, a high frequency of homozygotes was observed in patients presenting with the clinical symptoms of MCADD, but a relatively lower frequency of homozygotes were found in patients identified through newborn screening [2, 6, 16]. In addition, the frequency of the c.985A>G mutation is much higher in Caucasians than in Asians [6, 10, 17, 18]. The c.449_452delCTGA mutation, which was identified in the 2 patients in the present report, was first reported in 2 of 3 Japanese patients with MCADD in 2005 and also detected in 1 Korean patient [10, 12]. Prior to this study, the same mutation was detected in 8 of 11 Japanese patients with MCADD and 1 Korean patient with MCADD and was not reported in Caucasian patients [9-12]. Thus, the allele frequency of the c.449_452delCTGA mutation, including the 2 present cases, is 46.2% (12/26 alleles), making this mutation the most common mutation associated with MCADD in East Asians. In the light of the novel mutation presented here and previous reports on MCADD in East Asians, we expect that the distribution of ACADM mutations will vary according to ethnic origin.

In the past, there have been several previous reports on the genotype-phenotype correlation in MCADD patients. The homozygosity of the c.985A>G mutation has been reported to indicate a high level of plasma octanoylcarnitine [14, 19] and an increased risk of developing of adverse events [20]. However, the pathogenic effects of the majority of mutations in the ACADM gene have not been assessed. A previous case report described a Japanese patient with the c.449_452delCTGA and c.1189T>A mutations, and these mutations were identical to that of Patient 2 in our present report. In this report, the patient experienced hypoglycemia, vomiting, and lethargy that seemed to have triggered due to infections after the age of 7 months and was diagnosed with the disorder after biochemical tests [11]. Therefore, a close follow-up is needed to check for the development of hypoglycemia and other symptoms in our patient.

The novel ACADM c.461T>G (p.L154W) mutation was not found in 170 healthy subjects. Although leucine at codon 154 is not conserved in all species, searches in the evolutionary annotation database (http://jbirc.jbic.or.jp/evola/search.html) revealed that it is conserved in 12 among 14 species. All the mutations registered in Human gene mutation database (HGMD, http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php) are not conserved in all species. In addition, in-silico prediction analysis does not perfectly predict all mutations. Previous studies reported that scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) predicted about 70% of substitutions annotated as involved in disease as damaging, and about 80% of the nonsynonymous SNPs found to affect protein function in patients. PolyPhen was also reported to have similar sensitivity [21, 22].

The relationship between genotype and phenotype of the c.449_452delCTGA mutation, which was detected in both our patients and in other Asian patients, has not been clearly defined. A previous report showed slight elevations of plasma octanoylcarnitine and/or decanoylcarnitine levels in the c.449_452delCTGA mutation carriers among the family members of the proband [10]. In the first case of this report, octanoylcarnitine level was moderately increased (2.19-2.59 µmol/L), and this was similar to the octanoylcarnitine level observed in infants with a single copy of the c.985A>G mutation (1.9-3.2 µmol/L). This was categorized as a severe mutation in previous reports [19, 23], and the patient did not present any clinical symptoms. Therefore, the novel c.461T>G mutation may be associated with a mild phenotype. However, we did not measure enzyme activity in our patients and did not perform acylcarnitine analysis in either of the parents of the first patient. Therefore, the apparent effect of the novel mutation on enzyme activity and acylcarnitine levels could not be assessed. It is also known that environmental factors, including diet and infections, can limit the evaluation of genotype effects. Two contrasting previous reports described one patient who had a homozygous frameshift mutation with no residual MCAD enzyme activity, but showed no severe clinical manifestations for several months after birth, and another compound heterozygote patient who had c.985A>G and another missense mutation and died unexpectedly a few days after birth [2, 3, 24]. Therefore, further data accumulation through clinical, biochemical, and molecular approaches is needed to evaluate the relationship between clinical phenotype and genotype.

In summary, we have described 2 Korean pediatric patients with MCADD that was diagnosed by molecular studies; 1 of the cases showed a novel mutation, c.461T>G, in the ACADM gene. We conclude that c.449_452delCTGA is a common mutation in Korean MCADD patients. We believe that this report will contribute to a better understanding of the genetic background in Asian MCADD patients. The detection of novel mutations and further molecular and biochemical studies are needed to establish genotype-phenotype correlations of MCADD and to manage the disease at an early stage.

References

1. Iafolla AK, Thompson RJ Jr, Roe CR. Medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency: clinical course in 120 affected children. J Pediatr. 1994; 124:409–415. PMID: 8120710.

2. Andresen BS, Dobrowolski SF, O'Reilly L, Muenzer J, McCandless SE, Frazier DM, et al. Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) mutations identified by MS/MS-based prospective screening of newborns differ from those observed in patients with clinical symptoms: identification and characterization of a new, prevalent mutation that results in mild MCAD deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 2001; 68:1408–1418. PMID: 11349232.

3. Andresen BS, Bross P, Udvari S, Kirk J, Gray G, Kmoch S, et al. The molecular basis of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency in compound heterozygous patients: is there correlation between genotype and phenotype? Hum Mol Genet. 1997; 6:695–707. PMID: 9158144.

4. Sander S, Janzen N, Janetzky B, Scholl S, Steuerwald U, Schäfer J, et al. Neonatal screening for medium chain acyl-CoA deficiency: high incidence in Lower Saxony (northern Germany). Eur J Pediatr. 2001; 160:318–319. PMID: 11388605.

5. Maier EM, Liebl B, Röschinger W, Nennstiel-Ratzel U, Fingerhut R, Olgemöller B, et al. Population spectrum of ACADM genotypes correlated to biochemical phenotypes in newborn screening for medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Hum Mutat. 2005; 25:443–452. PMID: 15832312.

6. Grosse SD, Khoury MJ, Greene CL, Crider KS, Pollitt RJ. The epidemiology of medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: an update. Genet Med. 2006; 8:205–212. PMID: 16617240.

7. Shigematsu Y, Hirano S, Hata I, Tanaka Y, Sudo M, Sakura N, et al. Newborn mass screening and selective screening using electrospray tandem mass spectrometry in Japan. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002; 776:39–48.

8. Yoon HR, Lee KR, Kang S, Lee DH, Yoo HW, Min WK, et al. Screening of newborns and high-risk group of children for inborn metabolic disorders using tandem mass spectrometry in South Korea: a three-year report. Clin Chim Acta. 2005; 354:167–180. PMID: 15748614.

9. Purevsuren J, Kobayashi H, Hasegawa Y, Mushimoto Y, Li H, Fukuda S, et al. A novel molecular aspect of Japanese patients with medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD): c.449-452delCTGA is a common mutation in Japanese patients with MCADD. Mol Genet Metab. 2009; 96:77–79. PMID: 19064330.

10. Ensenauer R, Winters JL, Parton PA, Kronn DF, Kim JW, Matern D, et al. Genotypic differences of MCAD deficiency in the Asian population: novel genotype and clinical symptoms preceding newborn screening notification. Genet Med. 2005; 7:339–343. PMID: 15915086.

11. Yokoi K, Ito T, Maeda Y, Nakajima Y, Ueta A, Nomura T, et al. Acylcarnitine profiles during carnitine loading and fasting tests in a Japanese patient with medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2007; 213:351–359. PMID: 18075239.

12. Tajima G, Sakura N, Yofune H, Nishimura Y, Ono H, Hasegawa Y, et al. Enzymatic diagnosis of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency by detecting 2-octenoyl-CoA production using high-performance liquid chromatography: a practical confirmatory test for tandem mass spectrometry newborn screening in Japan. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005; 823:122–130.

13. Matsubara Y, Kraus JP, Ozasa H, Glassberg R, Finocchiaro G, Ikeda Y, et al. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of cDNA encoding the entire precursor of rat liver medium chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1987; 262:10104–10108. PMID: 3611054.

14. Waddell L, Wiley V, Carpenter K, Bennetts B, Angel L, Andresen BS, et al. Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: genotype-biochemical phenotype correlations. Mol Genet Metab. 2006; 87:32–39. PMID: 16291504.

15. Van Hove JL, Zhang W, Kahler SG, Roe CR, Chen YT, Terada N, et al. Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency: diagnosis by acylcarnitine analysis in blood. Am J Hum Genet. 1993; 52:958–966. PMID: 8488845.

16. Zschocke J, Schulze A, Lindner M, Fiesel S, Olgemöller K, Hoffmann GF, et al. Molecular and functional characterisation of mild MCAD deficiency. Hum Genet. 2001; 108:404–408. PMID: 11409868.

17. Nagao M. Frequency of 985A-to-G mutation in medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase gene among patients with sudden infant death syndrome, Reye syndrome, severe motor and intellectual disabilities and healthy newborns in Japan. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1996; 38:304–307. PMID: 8840534.

18. Tanaka K, Gregersen N, Ribes A, Kim J, Kølvraa S, Winter V, et al. A survey of the newborn populations in Belgium, Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Bulgaria, Spain, Turkey, and Japan for the G985 variant allele with haplotype analysis at the medium chain Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase gene locus: clinical and evolutionary consideration. Pediatr Res. 1997; 41:201–209. PMID: 9029639.

19. Zytkovicz TH, Fitzgerald EF, Marsden D, Larson CA, Shih VE, Johnson DM, et al. Tandem mass spectrometric analysis for amino, organic, and fatty acid disorders in newborn dried blood spots: a two-year summary from the New England Newborn Screening Program. Clin Chem. 2001; 47:1945–1955. PMID: 11673361.

20. Hsu HW, Zytkovicz TH, Comeau AM, Strauss AW, Marsden D, Shih VE, et al. Spectrum of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency detected by newborn screening. Pediatrics. 2008; 121:e1108–e1114. PMID: 18450854.

21. Flanagan SE, Patch AM, Ellard S. Using SIFT and PolyPhen to predict loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010; 14:533–537. PMID: 20642364.

22. Ng PC, Henikoff S. Accounting for human polymorphisms predicted to affect protein function. Genome Res. 2002; 12:436–446. PMID: 11875032.

23. Arnold GL, Saavedra-Matiz CA, Galvin-Parton PA, Erbe R, Devincentis E, Kronn D, et al. Lack of genotype-phenotype correlations and outcome in MCAD deficiency diagnosed by newborn screening in New York State. Mol Genet Metab. 2010; 99:263–268. PMID: 20036593.

24. Andresen BS, Bross P, Jensen TG, Winter V, Knudsen I, Kølvraa S, et al. A rare disease-associated mutation in the medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) gene changes a conserved arginine, previously shown to be functionally essential in short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD). Am J Hum Genet. 1993; 53:730–739. PMID: 8102510.

Fig. 1

ACADM mutations detected by sequence analysis. Compound heterozygote consisting of a known mutation and a novel mutation in Patient 1. The known maternally-derived allele was a 4-bp deletion at position 449 to 452 in exon 6, altering codon 153 from a proline to a termination codon (p.Thr150ArgfsX4). The novel mutant allele originated from the patient's father and was a T to G transition at position 461 in exon 6, resulting in a leucine to tryptophan change at codon 154 (p.L154W).

Fig. 2

Diagram of protein structure near the c.461T>G (p.L154W) mutation. (A) Leu154 lies on the loop between the N-terminal α domain and β domain, shown in sky blue. (B) The novel Leu154Trp mutation produces side-chain clash with Glu152 (dotted pink line). Hydrogen bonds are shown by the dotted green lines.

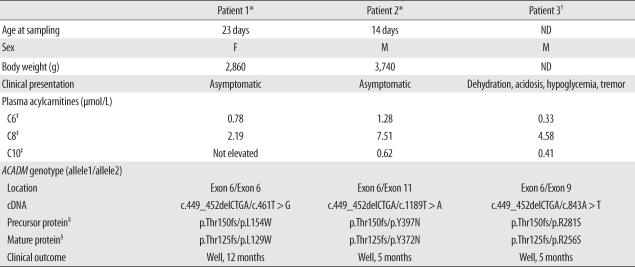

Table 1

Clinical, biochemical and molecular features of Korean patients with MCADD

*Identified in the present report; †Ref. [10]; ‡C6, hexanoylcarnitine; C8, octanoylcarnitine; C10, decanoylcarnitine; §The cDNA of the ACADM gene encodes the entire protein of 421-amino acid including a 25-amino acid leader and a 396-amino acid mature polypeptide [13].

Abbreviations: MCADD, medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency; ND, not determined; ACADM, acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium-chain.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download