Abstract

Alpha 1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency is a genetic disorder that primarily affects the lungs and liver. While AAT deficiency is one of the most common genetic disorders in the Caucasian population, it is extremely rare in Asians. Here, we report the case of a 36-year-old Korean woman with AAT deficiency who visited the emergency department of our hospital for the treatment of progressive dyspnea that had begun 10 years ago. She had never smoked. Chest computed tomography revealed panlobular emphysema in both lungs, which suggested AAT deficiency. The serum AAT level was 33 mg/dL (reference interval: 90-200 mg/dL). Four exons of the SERPINA1 gene, which is responsible for AAT deficiency, and their flanking regions were analyzed by PCR-direct sequencing. The patient was found to have 1 missense mutation (c.230C>T, p.Ser77Phe; Siiyama) and 1 frameshift mutation (c.1158dupC, p.Glu387ArgfsX14; QOclayton). This is the first Korean case of AAT deficiency confirmed by genetic analysis and the second case of a compound heterozygote of Siiyama and QOclayton, the first case of which was reported from Japan.

Alpha 1-antitrypsin (AAT) is a serine protease inhibitor encoded by the SERPINA1 gene. The protein is synthesized in the liver and circulates in serum to reach its target organs including the lungs. It inhibits various proteases and protects alveolar tissue against neutrophil elastase, thereby preventing destruction of these tissues. In patients with defective SERPINA1 genes, i.e., patients with AAT deficiency, the uninhibited elastase may damage the alveoli and cause early-onset emphysema. Moreover, abnormally folded and polymerized AAT may remain in hepatocytes, thereby forming intracellular inclusions and inducing liver injury [1, 2].

PiZ and PiS, which are considered as the products of the major alleles responsible for AAT deficiency, show considerable ethnic differences. PiZ is the most common deficient variant, especially in Northern and Western Europe, with plasma levels less than 50 mg/dL in homozygotes, whereas PiS is more frequent in the Mediterranean population with plasma levels about 60% of normal [1]. The estimated gene frequencies of PiZ and PiS in Koreans were 0.0061 and 0.0031, respectively, which were significantly lower than those observed in Caucasians. About 7,000 individuals are expected to have deficient allele combinations [2]. However, there have been no reports yet on AAT deficiency in Korea. In this report, we present a case of AAT deficiency in a Korean woman and elucidate her genetic characteristics.

A 36-year-old woman visited our emergency department with progressive dyspnea. The patient started experiencing dyspnea on exertion 10 years ago, and the condition exacerbated gradually. After experiencing pneumonia 3 months ago, her symptoms worsened and her daily activities were restricted. Two weeks before the visit, she experienced symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection (intermittent fever, cough, sputum, and sore throat) and dyspnea, which was observed even when the patient was in a resting state. Chest computed tomography revealed diffuse severe panlobular emphysema in both lungs, which suggested AAT deficiency (Fig. 1). Pulmonary function tests showed a severe obstructive pattern with positive bronchodilator response, increased residual volume, and decreased diffusing capacity. Serum AAT levels, measured by using nephelometry (BNII, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Newark, DE, USA), significantly decreased to 33 mg/dL (reference interval: 90-200 mg/dL). She had never smoked nor did she show a definite risk of environmental exposure to harmful dusts or noxious gases. Physical examination and laboratory findings showed no evidence of hepatic dysfunction.

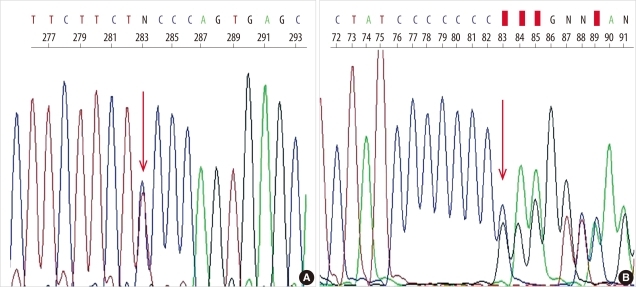

We suspected AAT deficiency and performed genetic analysis of the SERPINA1 gene. All 4 coding exons of the SERPINA1 gene and their flanking regions (NC_000014.8, NM_00102235.2) were analyzed by PCR-direct sequencing using primers reported in a previous study [3]. The allelic backbone of the SERPINA1 gene was M1 (Val237, numbered from a methionine at translation initiation site) and 2 sequence variations were identified-c.230C>T and c.1158dupC (Fig. 2). Substitution of cytosine by thymine leads to the substitution of serine by phenylalanine at codon 77 (p.Ser77Phe) and duplication of cytosine yields a frameshift mutation with a premature stop codon (p.Glu387ArgfsX14). These variations were found in previous reports and corresponded to a deficient allele, Siiyama, and a null allele, QOclayton [4, 5].

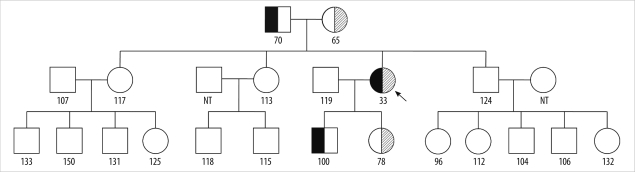

The patient's pedigree (Fig. 3) shows that the patient's father and son had the QOclayton alleles, and the patient inherited the Siiyama allele from her mother and transferred it to her daughter. However, none of the patient's siblings harbored the mutations. Serum AAT levels of the carriers, i.e., the parents and the children of the patients, were less than or approximately equal to the lower reference interval limit (65-100 mg/dL).

The patient is being treated with a bronchodilator and is scheduled to undergo lung transplantation.

A 36-year-old woman, without any risk factors developed severe emphysema and showed notably decreased AAT level in her serum. The patient was found to be a compound heterozygote for a substitution and a duplication mutation in the SERPINA1 gene.

The Siiyama allele, which is formed by a missense variation, was first described by Seyama et al. in a Japanese patient [4]. The substitution occurs in one of the conserved regions determined by Huber and Carrell [6] and is thought to affect the three-dimensional structure of the protein. The Siiyama allele is relatively prevalent in Japan [7].

Another duplicational variation causing a frameshift (c.1158dupC) was initially reported to yield a null allele, QOsaarbruecken, in the allele backbone of M1(Ala237) [8]. Our patient showed the same variation in M1 (Val237), and the resultant allele was designated as QOclayton [5]. In transfection studies, this allele may produce a normal amount of mRNA but the protein remains in rough endoplasmic reticulum and cannot be secreted outside the cells [5].

We described the protein variations in a codon numbered from the methionine residue at the translation initiation site. However, the first 24 amino acids of AAT act as a signal peptide [9, 10], and therefore, many studies numbered the codon from the glutamic acid at the 25th position [5, 7, 11]. There is no consensus about this issue and many articles and/or databases designate the same variations with different numbers [12, 13]. Therefore, careful attention should be paid when researchers report variations or cite other reports.

Measurement of serum AAT levels is a common procedure and may be used as an initial screening test. However, several points should be considered when interpreting the results. First, different methods for AAT measurement have different reference intervals, with the values for radial immunodiffusion higher than those for nephelometry [1]. The techniques applied and their reference intervals should be considered when referring to other studies. Second, AAT is a positive acute phase reactant [14]. Some patients may present with symptoms and/or signs of infection. Thus, estimation of baseline levels may be difficult in some cases. Third, various combinations of normal alleles and deficient alleles may be associated with a borderline zone of AAT levels, and patients showing levels in this borderline zone should be subjected to further evaluation [1]. Finally, some patients may have dysfunctional alleles showing almost normal levels and decreased functions of AAT [15, 16]. As a result, AAT levels should be interpreted cautiously, and the diagnosis of AAT deficiency should not be judged solely on the basis of serum AAT levels.

This is the second case of a compound heterozygote of Siiyama and QOclayton; the first case was reported by a Japanese group [11]. The clinical, radiologic, and laboratory findings in their report are similar to those in our case, except for the smoking history. The early onset and severity of the disease in our case can be attributed to the significantly decreased levels of AAT, which was caused by the compound heterozygous genotype of a deficient allele and a null allele.

In summary, we identified a case of AAT deficiency in Korea and studied the causative genetic variations. The patient was a compound heterozygote of Siiyama and QOclayton, and this genotype was responsible for the disease. A study of the patient's pedigree showed that she had inherited 1 allele from each parent. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a genetically confirmed case of AAT deficiency in Korea. The genetic constitutions of the SERPINA1 gene in Koreans might be quite different from those in other races, and targeted mutation analysis for PiZ and/or PiS may not work efficiently. Analysis of the entire exons and their flanking regions may be needed for genetic analysis of the patients suspected to have AAT deficiency, until more cases reveal the genetic composition in Korea.

References

1. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: standards for the diagnosis and management of individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003; 168:818–900. PMID: 14522813.

2. de Serres FJ. Worldwide racial and ethnic distribution of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency: summary of an analysis of published genetic epidemiologic surveys. Chest. 2002; 122:1818–1829. PMID: 12426287.

3. Ferrarotti I, Scabini R, Campo I, Ottaviani S, Zorzetto M, Gorrini M, et al. Laboratory diagnosis of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Transl Res. 2007; 150:267–274. PMID: 17964515.

4. Seyama K, Nukiwa T, Takabe K, Takahashi H, Miyake K, Kira S. Siiyama (serine 53 [TCC] to phenylalanine 53 [TTC]). A new alpha 1-antitrypsin-deficient variant with mutation on a predicted conserved residue of the serpin backbone. J Biol Chem. 1991; 266:12627–12632. PMID: 1905728.

5. Brantly M, Lee JH, Hildesheim J, Uhm CS, Prakash UB, Staats BA, et al. alpha1-antitrypsin gene mutation hot spot associated with the formation of a retained and degraded null variant [corrected; erratum to be published]. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997; 16:225–231. PMID: 9070606.

6. Huber R, Carrell RW. Implications of the three-dimensional structure of alpha 1-antitrypsin for structure and function of serpins. Biochemistry. 1989; 28:8951–8966. PMID: 2690952.

7. Seyama K, Nukiwa T, Souma S, Shimizu K, Kira S. Alpha 1-antitrypsin-deficient variant Siiyama (Ser53[TCC] to Phe53[TTC]) is prevalent in Japan. Status of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency in Japan. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995; 152:2119–2126. PMID: 8520784.

8. Faber JP, Poller W, Weidinger S, Kirchgesser M, Schwaab R, Bidlingmaier F, et al. Identification and DNA sequence analysis of 15 new alpha 1-antitrypsin variants, including two PI*Q0 alleles and one deficient PI*M allele. Am J Hum Genet. 1994; 55:1113–1121. PMID: 7977369.

9. Carrell RW, Jeppsson JO, Laurell CB, Brennan SO, Owen MC, Vaughan L, et al. Structure and variation of human alpha 1-antitrypsin. Nature. 1982; 298:329–334. PMID: 7045697.

10. P01009(A1AT_Human). Reviewed, UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot. Updated on May 2011. http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P01009.

11. Miyahara N, Seyama K, Sato T, Fukuchi Y, Eda R, Takeyama H, et al. Compound heterozygosity for alpha-1-antitrypsin (S[iiyama] and QO[clayton]) in an Oriental patient. Intern Med. 2001; 40:336–340. PMID: 11334395.

12. Cooper DN, Ball EV, Stenson PD, Phillips AD, Shaw K, Mort ME. The human gene mutation database at the institute of medical genetics in cardiff. Updated on Jun 2005. http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php.

13. Husami A, editor. LOVD gene hompage. Updated on May 2010. https://research.cchmc.org/LOVD/home.php?select_db=SERPINA1.

14. McPherson RA. McPherson RA, Pincus MR, editors. Specific proteins. Henry's clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods. 2007. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders;p. 236–241.

15. Okayama H, Brantly M, Holmes M, Crystal RG. Characterization of the molecular basis of the alpha 1-antitrypsin F allele. Am J Hum Genet. 1991; 48:1154–1158. PMID: 2035534.

16. Lewis JH, Iammarino RM, Spero JA, Hasiba U. Antithrombin Pittsburgh: an alpha1-antitrypsin variant causing hemorrhagic disease. Blood. 1978; 51:129–137. PMID: 412531.

Fig. 1

(A) Chest radiograph of the patient shows hyperinflated lungs. (B) Chest computed tomography of the patient at the initial visit. Bilateral diffuse emphysema is observed in lungs.

Fig. 2

The chromatogram obtained by sequencing of SERPINA1 gene. (A) A missense mutation (c.230C>T, p.Ser77Phe) corresponds to the Siiyama allele. (B) A frameshift mutation (c.1158dupC, p.Glu387ArgfsX14) indicates the QOclayton allele.

Fig. 3

The patient's pedigree. The proband is indicated by an arrow. The number below each individual represents the alpha-1antitrypsin level in serum (mg/dL; reference interval 90-200 mg/dL). The QOclayton allele is indicated by fully filled symbols and the Siiyama allele by the symbols filled with oblique lines. The parents and children of the patient were heterozygotes for Siiyama or QOclayton, as expected. NT represents not tested.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download