Abstract

Factor XI (FXI) deficiency is a rare autosomal recessive coagulation disorder most commonly found in Ashkenazi and Iraqi Jews, but it is also found in other ethnic groups. It is a trauma or surgery-related bleeding disorder, but spontaneous bleeding is rarely seen. The clinical manifestation of bleeding in FXI deficiency cases is variable and seems to poorly correlate with plasma FXI levels. The molecular pathology of FXI deficiency is mutation in the F11 gene on the chromosome band 4q35. We report a novel mutation of the F11 gene in an 18-year-old asymptomatic Korean woman with mild FXI deficiency. Pre-operative laboratory screen tests for lipoma on her back revealed slightly prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (45.2 sec; reference range, 23.2-39.4 sec). Her FXI activity (35%) was slightly lower than the normal FXI activity (reference range, 50-150%). Direct sequence analysis of the F11 gene revealed a heterozygous A to G substitution in nucleotide 1517 (c.1517A>G) of exon 13, resulting in the substitution of aspartic acid with glycine in codon 506 (p.Asp506Gly). To the best of our knowledge, the Asp506Gly is a novel missense mutation, and this is the first genetically confirmed case of mild FXI deficiency in Korea.

Factor XI (FXI) is a zymogen of the serine protease FXIa, which is an essential component in the intrinsic blood coagulation cascade, and functions through the activation of factor IX [1, 2]. FXI is produced in the liver and circulates in plasma as a disulfide-linked homodimer involved in non-covalent interaction with high-molecular-weight kininogen (HK) [3]. Each FXI monomer (80 kDa) is made up of 4 N-terminal apple domains (A1-A4) and a C-terminal trypsin like catalytic domain [4].

The human FXI gene (F11), which encodes the FXI protein, is located on the long arm of chromosome 4 (4q35) with a genome size of approximately 23 kb. The gene consists of 15 exons and 14 introns. Exon 1 corresponds to the 5'-untranslated region, exon 2 encodes the signal peptide, and exons 3-15 encode the mature FXI molecule [5].

Hereditary FXI deficiency (also known as hemophilia C) was first described as a hemophilia-like syndrome by Rosenthal et al. [6] in 1953. It is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait that may arise because of a wide range of mutations, including missense, nonsense, splice-site, insertion, and deletion mutations, within the F11 gene [4].

We report a case of a Korean woman with mild factor XI deficiency who was harboring a novel heterozygous mutation in the F11 gene. Only 8 cases of FXI deficiency have been reported in Korea, of which only 1 case has been genetically confirmed to be a case of severe FXI deficiency [7-11]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first genetically confirmed case of mild FXI deficiency in Korea.

An 18-year-old Korean woman visited the outpatient clinic for resection of a lipoma on her back. No apparent abnormal bleeding tendency was noted in her personal or familial history. Preoperative laboratory screen tests revealed that the patient had prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT, 45.2 sec; reference range, 23.2-39.4 sec; SynthASil APTT; Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA, USA), normal prothrombin time (PT, 12.0 sec; reference range, 10.4-13.3 sec), and normal liver function. The prolonged aPTT was corrected by mixing the patient's plasma sample with the normal plasma in the ratio 1:1, and the results of the tests for lupus anticoagulants were negative. Coagulation factor assays showed normal levels of factor VIII (FVIII, 69%; reference range, 60-150%), and factor IX (FIX, 75%; reference range, 60-150%), but showed slightly decreased FXI activity (35%; reference range, 50-150%; STA-Deficient XI; Diagnostica Stago, Asnieres, France).

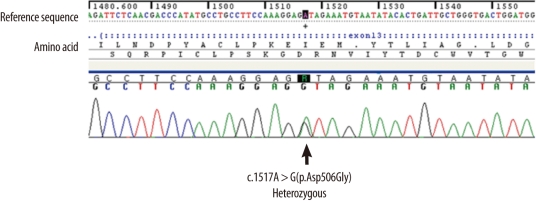

The patient's peripheral blood sample was obtained after receiving her informed consent. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral whole blood leukocytes by using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Each exon of the F11 gene and its flanking intronic sequences were amplified using PCR with primers (available upon request) designed by the authors and a thermal cycler (Model 9700; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Direct sequencing was performed with the same primer set and the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) by using the ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The patient sequences were compared with reference sequences (GenBank accession number, NM_000128.3) by using the Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) to identify any sequence variation. The guidelines of the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) were used to describe the sequence variations of DNA and protein. An amino acid variation was detected in exon 13 of F11 in the heterozygous condition. An A to G substitution at the nucleotide position 1517 (c.1517A>G) resulted in the replacement of aspartic acid with glycine at codon 506 (Asp506Gly) (Fig. 1). We conducted a control study with exon 13-targeted sequence analyses in 100 control chromosomes of 50 individuals of Korean descent with validated normal FXI activities since our literature search and search of the FXI deficiency mutation database [12] revealed Asp506Gly to be a novel variation. The frequency of the variation was 0%. Thus, Asp506Gly was confirmed to be a novel mutation.

Evolutionary conservation analysis of Asp506 performed using the ConSurf web server revealed an evolutionary conservation is score 4. Functional prediction of the consequences of Asp506Gly was performed using bioinformatics programs Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT) and Polymorphism Phenotyping (PolyPhen) [13, 14]. The results obtained were "tolerated" and "possibly damaging", respectively.

A crystal structure of the full-length form of FXI has been reported (PDB code: 2F83) [15]. We performed structural analysis to predict the functional role of Asp506 by using the PyMOL program (http://www.pymol/org/). In the crystal structure, the Asp506 residue in the C-terminal catalytic domain interacts with Arg202 in the A3 domain by forming a hydrogen bond (Fig. 2). The distance between the carboxylate of Asp506 and the guanidinium of Arg202 is 2.6 Å. The substitution of aspartic acid with glycine completely disrupts the hydrogen-bonding interaction with Arg202. This disruption may lead to a conformational change in the A3 domain.

Hereditary FXI deficiency is a common coagulation disorder in Ashkenazi and Iraqi Jews with a heterozygote frequency of 8% and 3.3%, respectively; however, it is very rarely seen in other ethnic groups, with a frequency of 1:1,000,000 [16]. Patients with FXI deficiency show mutations in the F11 gene encoding FXI. Type II (Glu117X) and type III (Phe283Leu) mutations are particularly prevalent in the Jewish population, and these 2 mutations account for approximately 95% of F11 mutations among the Jews [17-19]. However, a variety of mutations have been reported in other ethnic groups, with those prevalent among Ashkenazi and Iraqi Jews accounting for only a small percentage of the total population of disease alleles [20, 21]. Currently, the FXI deficiency mutation database contains information on 192 disease-causing mutations of the F11 gene, which was obtained from 487 patients with FXI deficiency reported in the literature [12].

Patients with FXI deficiency show wide variation in the manifestation of bleeding symptoms, and these manifestations are largely affected by the genotype and the site of injury. Patients with homozygous mutations usually have severe FXI deficiency (FXI activity <15%), whereas those with heterozygous mutations have mild/partial FXI deficiency (FXI activity, 20-50%) [22]. However, unlike the findings in hemophilia A and B, spontaneous bleeding is rarely seen even in patients with severe FXI deficiency. The common presentation of severe FXI deficiency is injury- or surgery-related bleeding, especially when the trauma involves anatomical sites with high fibrinolytic activity, such as the oral or nasal cavities, the prostate, and the uterus. In patients with heterozygous mutations, the bleeding risk has not been conclusively determined and is not well predicted by plasma FXI level [23].

In Korea, hereditary FXI deficiency is rare, and only 8 cases have been reported [7-11]. A history of spontaneous bleeding has not been reported even in patients with severe deficiency, except in 1 case with intermittent nasal bleeding, which was easily controlled. In most of the cases, the diagnosis of FXI deficiency was made on the basis of coagulation test results without molecular genetic study. Only 1 case, in which severe deficiency was observed due to compound heterozygous mutations (Val498Met and Tyr503ValfsX32) of the F11 gene, has been genetically confirmed to date [11]. The patient showed no spontaneous or postoperative bleeding despite the severely decreased FXI activity (1%). Our patient is the second genetically confirmed case of FXI deficiency and the first genetically confirmed case of mild FXI deficiency in Korea. In this patient, a slightly prolonged aPTT of 45.2 sec was accidentally detected during preoperative screening, and the patient had no personal history of bleeding symptoms. Further coagulation tests and molecular studies revealed that she had mild FXI deficiency with an FXI coagulant activity (FXI:C) of 35% because of a heterozygous novel missense mutation Asp506Gly in exon 13 of the F11 gene, which encodes the catalytic domain of FXI. The results of bioinformatics analysis predicted that Asp506Gly is tolerated or may show damaging effects on FXI function [14, 15]. Structural analysis shows that this mutation disrupts the hydrogen-bonding interaction with Arg202 on the A3 domain, which is involved in binding interactions with the substrate FIX and is therefore required for the activation of this substrate [24]. Thus, the mutation may cause a conformational change in the A3 domain, consequently reducing the activity of the FXI protein.

Management of mild/partial FXI deficiency is difficult because of the variability and unpredictability of the bleeding tendency [23, 25]. Prophylactic treatment is generally not required for patients who do not show hemostatic abnormalities. However, prophylactic treatment with desmopressin could be an option for patients with a history of bleeding [21]. Coagulation factor concentrates may be required for major surgery [23]. Our patient has not undergone an operation for the resection of the lipoma on her back; therefore, we need to follow up her clinical course.

In conclusion, we report a novel missense mutation in a catalytic domain of the FXI protein. The Asp506Gly mutation is associated with mild FXI deficiency and did not cause spontaneous bleeding in this case. This is the first report on a genetically confirmed case of mild FXI deficiency in Korea. Few genetically confirmed cases have been reported to date. Additional reports on the relation between coagulation and the FXI deficiency and molecular studies on FXI deficiency are needed to facilitate clinical decision-making.

References

1. Davie EW, Fujikawa K, Kisiel W. The coagulation cascade: initiation, maintenance, and regulation. Biochemistry. 1991; 30:10363–10370. PMID: 1931959.

2. Gailani D, Broze GJ Jr. Factor XI activation in a revised model of blood coagulation. Science. 1991; 253:909–912. PMID: 1652157.

3. Thompson RE, Mandle R Jr, Kaplan AP. Association of factor XI and high molecular weight kininogen in human plasma. J Clin Invest. 1977; 60:1376–1380. PMID: 915004.

4. Berber E. Molecular characterization of FXI deficiency. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2011; 17:27–32. PMID: 20308231.

5. Asakai R, Davie EW, Chung DW. Organization of the gene for human factor XI. Biochemistry. 1987; 26:7221–7228. PMID: 2827746.

6. Rosenthal RL, Dreskin OH, Rosenthal N. New hemophilia-like disease caused by deficiency of a third plasma thromboplastin factor. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1953; 82:171–174. PMID: 13037836.

7. Lee SH, Jeong MH, Sohn IS, Lim SY, Hong SN, Kang DG, et al. Successful management of a patient with factor XI deficiency and unstable angina by percutaneous coronary intervention. Korean Circ J. 2005; 35:860–863.

8. Cho YK, Lim JY, Jung YS, Park CH, Woo HO, Park BK, et al. Two cases of factor XI deficiency in sisters. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1998; 41:401–404.

9. Rha JY, Kook JH, Koon H, Yang SJ, Cho D, Ryang DW, et al. Three cases of factor XI deficiency. Korean J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001; 8:344–348.

10. Kim YS, Chung EY, Yoon JR, Han IS, Park AR, Kim TK, et al. Anesthetic experience of a patient with hereditary factor XI deficiency (Hemophilia C): A case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2009; 56:706–708.

11. Kwon MJ, Kim HJ, Bang SH, Kim SH. Severe factor XI deficiency in a Korean woman a novel missense mutation (Val498Met) and duplication G mutation in exon 13 of the F11 gene. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2008; 19:679–683. PMID: 18832909.

12. Saunders RE, Shiltagh N, Perkins SJ, Gomez K, Mellars G, Cooper C, editors. F XI deficiency mutation database. Updated on Sep 2009. http://www.factorxi.org.

13. Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003; 31:3812–3814. PMID: 12824425.

14. Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002; 30:3894–3900. PMID: 12202775.

15. Papagrigoriou E, McEwan PA, Walsh PN, Emsley J. Crystal structure of the factor XI zymogen reveals a pathway for transactivation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006; 13:557–558. PMID: 16699514.

16. Peyvandi F, Lak M, Mannucci PM. Factor XI deficiency in Iranians: its clinical manifestations in comparison with those of classic hemophilia. Haematologica. 2002; 87:512–514. PMID: 12010665.

17. Asakai R, Chung DW, Davie EW, Seligsohn U. Factor XI deficiency in Ashkenazi Jews in Israel. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:153–158. PMID: 2052060.

18. Shpilberg O, Peretz H, Zivelin A, Yatuv R, Chetrit A, Kulka T, et al. One of the two common mutations causing factor XI deficiency in Ashkenazi Jews (type II) is also prevalent in Iraqi Jews, who represent the ancient gene pool of Jews. Blood. 1995; 85:429–432. PMID: 7811996.

19. Peretz H, Mulai A, Usher S, Zivelin A, Segal A, Weisman Z, et al. The two common mutations causing factor XI deficiency in Jews stem from distinct founders: one of ancient Middle Eastern origin and another of more recent European origin. Blood. 1997; 90:2654–2659. PMID: 9326232.

20. Hancock JF, Wieland K, Pugh RE, Martinowitz U, Schulman S, Kakkar VV, et al. A molecular genetic study of factor XI deficiency. Blood. 1991; 77:1942–1948. PMID: 2018835.

22. Seligsohn U, Bolton-Maggs PH. Lee CA, Berntorp E, editors. Factor XI deficiency. Textbook of Haemophilia. 2010. 2nd ed. United Kingdom, UK: Wiley-Blackwell;p. 355–361.

23. Bolton-Maggs PH, Perry DJ, Chalmers EA, Parapia LA, Wilde JT, Williams MD, et al. The rare coagulation disorders--review with guidelines for management from the United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors' Organisation. Haemophilia. 2004; 10:593–628. PMID: 15357789.

24. Sun MF, Zhao M, Gailani D. Identification of amino acids in the factor XI apple 3 domain required for activation of factor IX. J Biol Chem. 1999; 274:36373–36378. PMID: 10593931.

25. Bolton-Maggs PH, Patterson DA, Wensley RT, Tuddenham EG. Definition of the bleeding tendency in factor XI-deficient kindreds--a clinical and laboratory study. Thromb Haemost. 1995; 73:194–202. PMID: 7792729.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download