Abstract

Streptococcus suis infection is an emerging zoonosis in Asia. The most common disease manifestation is meningitis, which is often associated with hearing loss and cochleovestibular signs. S. suis infection in humans mainly occurs among risk groups that have frequent exposure to pigs or raw pork. Here, we report a case of S. suis meningitis in a 67-yr-old pig carcass handler, who presented with dizziness and sensorineural hearing loss followed by headaches. Gram-positive diplococci were isolated from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood cultures and showed gray-white colonies with α-hemolysis. S. suis was identified from CSF and blood cultures by using a Vitek 2 system (bioMérieux, France), API 20 STREP (bioMérieux), and performing 16S rRNA and tuf gene sequencing. Even after receiving antibiotic treatment, patients with S. suis infection frequently show complications such as hearing impairment and vestibular dysfunction. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of S. suis meningitis in Korea. Prevention through public health surveillance is recommended, especially for individuals who have occupational exposures to swine and raw pork.

Streptococcus suis is an important swine pathogen associated with a wide range of diseases in pigs. The upper respiratory tract, genital, and alimentary tracts are the natural habitats of the pathogen in pigs [1]. S. suis is mainly transmitted to human beings by cutaneous contact with infected pigs or raw pork, especially when the skin has cuts and abrasions [2]. Human infection presents predominantly as acute meningitis or arthritis, but may also present with pneumonia, endophthalmitis, endocarditis, and fatal septicemia. Patients with S. suis meningitis can develop permanent hearing loss [1, 3, 4]. Since the first human case was reported in Denmark in 1968, over 700 cases have been reported worldwide; most are from the European and Asian countries [2, 5]. Here, we report the first case of S. suis meningitis in Korea.

Sixty seven-year-old man, working as a pig carcass handler, presented with hearing difficulty and dizziness followed by nausea and headache for 5 days. He had a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus. On admission, his temperature was 35.1℃, blood pressure was 86/65 mm Hg, pulse rate was at 61 beats per min, and respiratory rate was 19 breaths per min. Although he was alert and oriented, physical examination revealed neck stiffness and limb and gait ataxia. Laboratory investigation showed a leukocyte count of 10,190/mm3 with 90% polymorphonuclear cells and a platelet count of 87,000/mm3. The serum C-reactive protein level (30.0 mg/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (45 mm/hr) were elevated. The coagulation profile showed a slightly prolonged prothrombin time (15.5 sec, international normalized ratio 1.22) and elevated D-dimer levels (11.53 µg/mL). The serum glucose level was 257 mg/dL, and the serum creatinine level had increased to 1.69 mg/dL. The patient's cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was turbid and had 2,350 leukocytes/µL (polymorphonuclear cells, 81%), he had a protein concentration of 349.9 mg/dL, and a glucose concentration of 10 mg/dL (serum glucose level of 257 mg/dL). Therefore, bacterial meningitis was immediately suspected. After performing CSF analysis and 2 sets of peripheral blood cultures, empirical antibiotic treatment with intravenous ampicillin, ceftriaxone, and vancomycin was initiated.

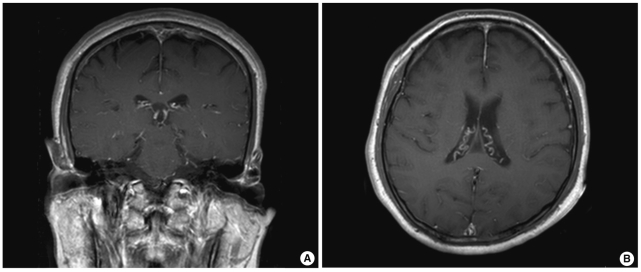

Computed tomographic (CT) scans of the head and temporal bone showed normal results. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed abnormal enhancement of the leptomeninges in both the cerebral hemispheres (Fig. 1). Pure-tone audiometry showed profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss.

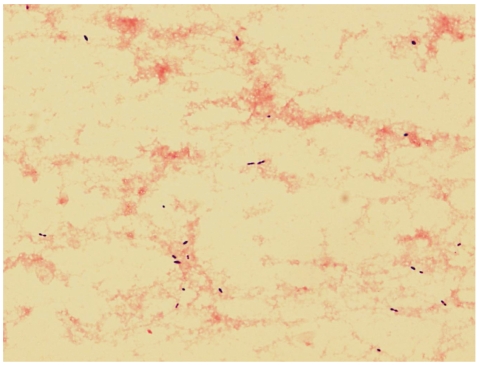

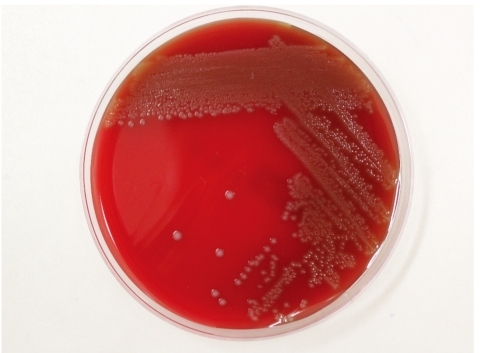

On day 2 at the hospital, aerobic bottles of both blood culture sets grew gram-positive diplococci after 8 hr of incubation in the BacT/Alert 3D system (bioMérieux Inc; Durham, NC, USA). CSF samples cultured in the thioglycollate broth also grew the same organisms (Fig. 2). Subinoculation on sheep blood agar plates was performed for both the CSF and blood cultures. After 24 hr of incubation at 35℃ in the presence of 5% CO2, we observed small gray-white colonies that showed catalase negativity, optochin resistance, and α-hemolytic activity. After prolonged incubation for 48 hr, large colonies were visible and the α-hemolysis was more pronounced (Fig. 3). This organism was identified as S. suis biotype II using the Vitek 2 Gram-Positive Identification (GPI) card (probability, 99.0%; which represents excellent identification [ID]); (bioMérieux; Marcy-l'Etoile, France) and the API 20 STREP (profile code 4771473, % ID 99.7%, T index 0.73; bioMérieux).

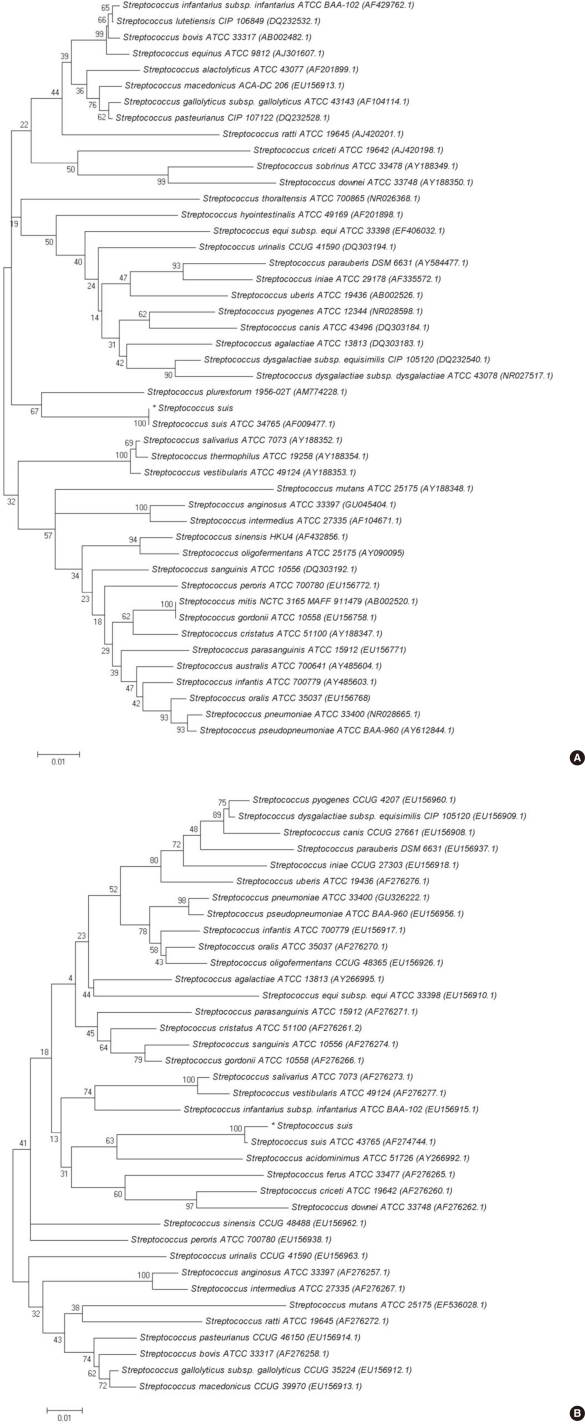

We performed 16S rRNA gene sequencing for the CSF isolate. The 16S rRNA gene fragments were amplified by standard methods according to CLSI guidelines [6]. Two subregions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using the following primer pairs: forward, 4F: 5'-TTG GAG AGT TTG ATC CTG GCT C-3' and reverse, 534R: 5'-TAC CGC GGC TGC TGG CAC-3' and forward, 27F: 5'-AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG-3' and reverse, 801R: 5'-GGC GTG GAC TTC CAG GGT ATC T-3'. The tuf gene fragments were amplified with the forward (55C-F: 5'-GCC AGT TGA GGA CGT ATT CT-3') and reverse (55C-R: 5'-CCA TTT CAG TAC CTT CTG GTA A-3') primers. Purified PCR products were sequenced directly by using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit 3.1 (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA, USA) on an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). A GenBank BLAST (The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) search revealed that 16S rRNA gene and tuf gene sequences of the isolate show 100% (664/664 bp) and 99% (407/409 bp) homology with the corresponding sequences of a previously sequenced S. suis strain, respectively (GenBank accession number, CP000837.1). For further phylogenetic analysis, the CSF isolate 16S rRNA and tuf gene sequences were aligned using ClustalW [7]. Phylogenetic trees (Fig. 4) were constructed using the neighbor-joining method by using the MEGA 5 software package (http://www.megasoftware.net) and Kim-ura two parameters as the substitution model [8-10]. The statistical significance of the phylogenies was assessed by bootstrap analysis with 1,000 pseudoreplicate datasets. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree.

Antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed using the MicroScan MICroSTREP plus panel (Dade Behring; West Sacramento, CA, USA). The CSF isolate was susceptible to all the antimicrobial agents tested (penicillin, ampicillin, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefepime, meropenem, vancomycin, and chloramphenicol). On the basis of the results of susceptibility test, the patient's antibiotic therapy was changed to intravenous penicillin G (24 million units over 24 hr).

Although the patient's headache gradually improved, he experienced continued dizziness, bilateral hearing loss, and showed symptoms of vestibular dysfunction. On day 16 at the hospital, an MRI of the internal auditory canal revealed abnormal enhancement of the vestibular cochlea on both sides, which was suggestive of bilateral labyrinthitis. On day 22 at the hospital, the patient was discharged and referred to a local hospital close to his home. Because the patient requested outpatient treatment, the parenteral antibiotic therapy was modified to once-daily dose of ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hr), as an alternative to 6 times-a-day administration of penicillin G.

After completing a 4-week course of parenteral antibiotic therapy, the patient continued to experience dizziness, hearing difficulty, and headache during the 5-week follow-up. It was subsequently determined that the patient had sustained a hand abrasion a week before disease presentation and continued to handle pig carcasses at work without any protection, such as wearing gloves.

S. suis is a gram-positive facultative anaerobe, which is coccoid or ovoid in shape and occurs as single cells, in pairs, or in short chains. On the basis of the capsular polysaccharides, 35 serotypes of S. suis have been identified. Although the serotype was not identified in this case, serotype 2 is most commonly associated with diseases in pigs and human beings and is the most frequently reported serotype worldwide [1, 11, 12]. Most S. suis strains produce narrow zones of α-hemolysis on sheep blood agar plates. S. suis serotype 2 colonies show α- and β-hemolysis on sheep and horse blood agar plates, respectively [13]. Because the growth of S. suis on sheep blood agar plates is commonly used to identify the species in routine diagnostic laboratories, this species may be mistaken for viridans streptococci. Although bacteriological diagnosis was made using commercial identification systems in this case, S. suis infections are often misidentified, or may remain undiagnosed [2]. S. suis is commonly misidentified and reported as Streptococcus species, α-hemolytic or viridans streptococci, Enterococcus faecalis, Aerococcus viridans, or even Streptococcus pneumoniae [2, 14]. An S. suis infection should be considered in regions with pig-farming industries or in patients who are in contact with pigs or raw pork, if optochin-resistant Streptococcus are cultured from a CSF sample obtained from a patient with meningitis. Further microbiological investigations are required for the identification of α-hemolytic streptococci other than S. pneumoniae.

Molecular techniques with PCR have improved the rate of detection of S. suis. The 16S RNA gene sequencing technique is a useful and definitive method for most Streptococcus spp. For certain genera or groups of microorganisms, the use of alternative gene targets such as the tuf gene is necessary, because some species may share 99% to 100% 16S rRNA sequence identity [6]. Thus, 16S rRNA and tuf gene sequencing were performed in this case. In phylogenetic analysis, the CSF isolate presented here was homologous with S. suis type strains based on 16S rRNA (GenBank accession number, AF009477.1) and tuf gene sequencing (AF274744.1), respectively (Fig. 4). Serotype-specific PCR assays and serological tests can be useful tools for the identification of S. suis serotypes [1, 15, 16]. Some commercial biochemical identification systems also report the biotype of S. suis (biotype I or II) [2]. Wertheim et al. suggested that the S. suis biotype should not be mistaken for serotype 1 or 2, as was done in some previous reports [2, 17, 18].

S. suis infections have been reported worldwide. However, the majority of human cases have occurred in Asia (China, Thailand, Vietnam, and Japan) [1, 2, 19]. S. suis infections in humans rarely occur in Korea. To date, only one S. suis infection in humans has been reported in Korea [20]. However, the possibility of undiagnosed S. suis infections cannot be excluded. Although most reports of S. suis infections are sporadic cases, outbreaks of human S. suis infections are infrequently reported. Of note, the 2005 outbreak that occurred in Sichuan Province, China, involved 215 cases and caused 38 deaths, emphasizing the importance of S. suis as an emerging zoonosis [21].

S. suis infections in humans are most often reported from countries where pig rearing is common, and the people who are in daily contact with pigs are usually affected. The relatively high mean-patient age, the almost complete absence of children in the case series, and the high male-to-female patient ratio support the notion that S. suis infection is principally an occupational disease [2, 4, 21-23]. In our case, the patient was exposed to S. suis through infected tissues of pig carcasses, which were handled without proper protection, such as gloves. Besides occupational exposure, processing or consuming uncooked or partially cooked pork products is also a risk factor for infection [2, 22-24]. Patients are generally healthy prior to infection with S. suis, although predisposing factors, such as diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, and malignancy have been reported [25].

S. suis infection is typically manifested as meningitis. One remarkable symptom of S. suis meningitis is sensorineural hearing loss, which may be reported by up to half of the patients either at presentation or a few days later. This hearing loss is often bilateral, profound, and permanent [3, 22]. De-afness with or without vestibular dysfunction is thought to be attributed to direct infection of the cochlea. S. suis is believed to enter the perilymph via the cochlear aqueduct through the lytic action of exotoxins [3]. Patients with S. suis meningitis may also show permanent incapacitation by vertigo and gait instability because of vestibular dysfunction. Such patients should immediately receive vestibular rehabilitation to improve their independence in daily activities [3, 26].

Analogous to protocols for any case of with suspected bacterial meningitis, immediate antibiotic administration is the first step in the treatment of bacterial meningitis. For empirical treatment, ceftriaxone with vancomycin (the same treatment dose and duration that is used for pneumococcal meningitis) is a good choice until the diagnosis is confirmed. S. suis is sensitive to many antibiotics [1, 2]. Thus, once S. suis is verified as an infectious agent, antibiotic treatment accompanied with other associated treatments is very effective. After the confirmation of the presence of an S. suis infection, patients are generally treated with penicillin G, accompanied by one or more other antibiotics including ceftriaxone, gentamicin, chloramphenicol, and ampicillin. Penicillin G (24 million units over 24 hr for at least 10 days) or ceftriaxone (2 g every 12 hr for at least 10 days) has been used successfully for the treatment of S. suis meningitis. Relapse of S. suis meningitis has been reported after 2 weeks of treatment with penicillin or ceftriaxone. However, the patients responded to a prolonged antibiotic treatment for 4-6 weeks [1, 2, 23, 27]. The use of dexamethasone as an adjunctive treatment to reduce mortality and improve the outcome of bacterial meningitis remains controversial [28]. Quick diagnosis and early antibiotic treatment are the most important factors in decreasing the damage caused by S. suis infection. Therefore, in patients presenting with meningitis, if characteristic features such as prominent and early hearing loss are observed, S. suis should be considered regardless of the patient's occupational background.

Currently, there is no human S. suis vaccine. Therefore, prevention of transmission to humans depends on the control of spread of S. suis from infected pigs. Improvement of pig-raising conditions and pig vaccination are both effective methods to reduce the risk of human infection. Furthermore, increasing awareness of the disease by educating high-risk populations is also expected to help avoid human infection. Individuals with open wounds should wear gloves when handling raw or uncooked pork, and anyone who prepares pork should wash his or her hands and clean all the utensils thoroughly after contact [1, 29].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of S. suis meningitis in humans in Korea. This case should remind clinicians that S. suis meningitis affects people who are in daily contact with pigs. During diagnosis, S. suis infection should not be confused with infections caused by other Streptococcus species. Prevention through public he-alth surveillance is needed, and people with occupational exposures to swine and/or pork products should be educated. Increased awareness among both clinicians and microbiologists is required to fully appreciate the importance of S. suis infection as an emerging zoonosis and to promote early diagnosis and prevention of sequelae.

References

1. Lun ZR, Wang QP, Chen XG, Li AX, Zhu XQ. Streptococcus suis: an emerging zoonotic pathogen. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007; 7:201–209. PMID: 17317601.

2. Wertheim HF, Nghia HD, Taylor W, Schultsz C. Streptococcus suis: an emerging human pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2009; 48:617–625. PMID: 19191650.

3. Tan JH, Yeh BI, Seet CS. Deafness due to haemorrhagic labyrinthi tis and a review of relapses in Streptococcus suis meningitis. Singapore Med J. 2010; 51:e30–e33. PMID: 20358139.

4. Wangkaew S, Chaiwarith R, Tharavichitkul P, Supparatpinyo K. Streptococcus suis infection: a series of 41 cases from Chiang Mai University Hospital. J Infect. 2006; 52:455–460. PMID: 16690131.

5. Perch B, Kristjansen P, Skadhauge K. Group R streptococci pathogenic for man. Two cases of meningitis and one fatal case of sepsis. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1968; 74:69–76. PMID: 5700279.

6. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Interpretive criteria for identification of bacteria and fungi by DNA target sequencing; approved guideline. Document MM18-A. 2008. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

7. Aiyar A. The use of CLUSTAL W and CLUSTAL X for multiple sequence alignment. Methods Mol Biol. 2000; 132:221–241. PMID: 10547838.

8. Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987; 4:406–425. PMID: 3447015.

9. Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980; 16:111–120. PMID: 7463489.

10. Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007; 24:1596–1599. PMID: 17488738.

11. Gottschalk M, Segura M. The pathogenesis of the meningitis caused by Streptococcus suis: the unresolved questions. Vet Microbiol. 2000; 76:259–272. PMID: 10973700.

12. Facklam R. What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002; 15:613–630. PMID: 12364372.

13. Heidt MC, Mohamed W, Hain T, Vogt PR, Chakraborty T, Do-mann E. Human infective endocarditis caused by Streptococcus suis serotype 2. J Clin Microbiol. 2005; 43:4898–4901. PMID: 16145171.

14. Donsakul K, Dejthevaporn C, Witoonpanich R. Streptococcus suis infection: clinical features and diagnostic pitfalls. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2003; 34:154–158. PMID: 12971528.

15. Wisselink HJ, Joosten JJ, Smith HE. Multiplex PCR assays for simultaneous detection of six major serotypes and two virulence-associated phenotypes of Streptococcus suis in tonsillar specimens from pigs. J Clin Microbiol. 2002; 40:2922–2929. PMID: 12149353.

16. Smith HE, Veenbergen V, van der Velde J, Damman M, Wisselink HJ, Smits MA. The cps genes of Streptococcus suis serotypes 1, 2, and 9: development of rapid serotype-specific PCR assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1999; 37:3146–3152. PMID: 10488168.

17. Lee GT, Chiu CY, Haller BL, Denn PM, Hall CS, Gerberding JL. Streptococcus suis meningitis, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008; 14:183–185. PMID: 18258107.

18. Kopić J, Paradzik MT, Pandak N. Streptococcus suis infection as a cause of severe illness: 2 cases from Croatia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002; 34:683–684. PMID: 12374361.

19. Willenburg KS, Sentochnik DE, Zadoks RN. Human Streptococcus suis meningitis in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:1325. PMID: 16554543.

20. Kim H, Lee SH, Moon HW, Kim JY, Hur M, Yun YM. Streptococcus suis Causes Septic Arthritis and Bacteremia: Phenotypic Characterization and Molecular Confirmation. Korean J Lab Med. 2011; 31:115–117. PMID: 21474987.

21. Yu H, Jing H, Chen Z, Zheng H, Zhu X, Wang H, et al. Human Streptococcus suis outbreak, Sichuan, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006; 12:914–920. PMID: 16707046.

22. Kay R, Cheng AF, Tse CY. Streptococcus suis infection in Hong Kong. QJM. 1995; 88:39–47. PMID: 7894987.

23. Mai NT, Hoa NT, Nga TV, Linh le D, Chau TT, Sinh DX, et al. Streptococcus suis meningitis in adults in Vietnam. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 46:659–667. PMID: 19413493.

24. Ma E, Chung PH, So T, Wong L, Choi KM, Cheung DT, et al. Streptococcus suis infection in Hong Kong: an emerging infectious disease? Epidemiol Infect. 2008; 136:1691–1697. PMID: 18252026.

25. Huang YT, Teng LJ, Ho SW, Hsueh PR. Streptococcus suis infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2005; 38:306–313. PMID: 16211137.

26. Strupp M, Arbusow V, Maag KP, Gall C, Brandt T. Vestibular exercises improve central vestibulospinal compensation after vestibular neuritis. Neurology. 1998; 51:838–844. PMID: 9748036.

27. Halaby T, Hoitsma E, Hupperts R, Spanjaard L, Luirink M, Jacobs J. Streptococcus suis meningitis, a poacher's risk. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000; 19:943–945. PMID: 11205632.

28. Greenwood BM. Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2507–2509. PMID: 18077815.

29. Durand F, Perino CL, Recule C, Brion JP, Kobish M, Guerber F, et al. Bacteriological diagnosis of Streptococcus suis meningitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001; 20:519–521. PMID: 11561816.

Fig. 1

Brain MRIs. T1 weighted gadolinium enhanced axial (A) and coronal (B) images reveal diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement in both cerebral hemispheres.

Fig. 2

Gram stain of Streptococcus suis of cerebrospinal fluid showed Gram positive diplococci under a light microscope (×1,000).

Fig. 3

Gray-whitish, α-hemolytic colonies of Streptococcus suis on sheep blood agar plate at 35℃ in the presence of 5% CO2 after 24 hr incubation.

Fig. 4

Molecular phylogenetic tree constructed by neighbor-joining method using the 16s rRNA (A) and tuf gene (B) sequences of our S. suis isolate and various Streptococcus species. Reference sequences were from the type strains of the species and accession numbers are given in parentheses. All names and accession numbers are given as cited in the GenBank database.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download